Mr. Wells, in The World of William Clissold, presents, not precisely his own mind as it has developed on the basis of his personal experience and way of life, but—shifting his angle—a point of view based on an experience mainly different from his own, that of a successful, emancipated, semi-scientific, not particularly high-brow, English business man. The result is not primarily a work of art. Ideas, not forms, are its substance. It is a piece of educational writing—propaganda, if you like—an attempt to convey, to the very big public, attitudes of mind already partly familiar to the very small public.

The book is an omnium gatherum. I will select two emergent themes of a quasi-economic character. Apart from these, the main topic is women and some of their possible relationships in the modern world to themselves and to men of the Clissold type. This is treated with great candor, sympathy, and observation. It leaves, and is meant to leave, a bitter taste.

The first of these themes is a violent protest against conservatism, an insistent emphasis on the necessity and rapidity of change, the folly of looking backwards, the danger of inadaptibility. Mr. Wells produces a, curious sensation, nearly similar to that of some of his earlier romances, by contemplating vast stretches of time backwards and forwards which give an impression of slowness (no need to hurry in eternity), yet accelerating the Time Machine as he reaches the present day so that now we travel at an enormous pace and no longer have millions of years to turn round in. The conservative influences in our life are envisaged as dinosaurs whom literal extinction is awaiting just ahead. The contrast comes from the failure of our ideas, our conventions, our prejudices to keep up with the pace of material change. Our environment moves too much faster than we do. The walls of our traveling compartment are bumping our heads. Unless we hustle, the traffic will run us down. Conservatism is no better than suicide. Woe to our dinosaurs!

This is one aspect. We stand still at our peril. Time flies. But there is another aspect of the same thing—and this is where Clissold comes in. What a bore for the modern man, whose mind in his active career moves with the times, to stand still in his observances and way of life! What a bore are the feasts and celebrations with which London or New York crowns success! What a bore to go through the social contortions which have lost significance, and conventional pleasures which no longer please! The contrast between the exuberant, constructive activity of a prince of modern commerce and the lack of an appropriate environment for him out of office hours is acute. Moreover, there are wide stretches in the career of moneymaking which are entirely barren and non-constructive. There is a fine passage in the first volume about the profound, ultimate boredom of City men. Clissold's father, the company promoter and speculator, falls first into megalomania and then into fraud, because he is bored. I do not doubt that this same thing is true of Wall Street. Let us, therefore, mold with both hands the plastic material of social life into our own contemporary image.

We do not merely belong to a latter-day age—we are ourselves in the literal sense older than our ancestors were in the years of our maturity and our power. Mr. Wells brings out strongly a too much neglected feature of modern life, that we live much longer than formerly, and, what is more important, prolong our health and vigor into a period of life which was formerly one of decay, so that the average man can now look forward to a duration of activity which hitherto only the exceptional could anticipate. I can add, indeed, a further fact, which Mr. Wells overlooks (I think), likely to emphasize this yet further in the next fifty years as compared with the last fifty years—namely, that the average age of a rapidly increasing population is much less than that of a stationary population. For example, in the stable conditions to which England and probably the United States also, somewhat later, may hope to approximate in the course of the next two generations, we shall somewhat rapidly approach to a position in which, in proportion to population, elderly, people (say, sixty-five years of age and above) will be nearly 100 percent, and middle-aged people (say, forty-five years of age and above), nearly 50 percent more numerous than in the recent past. In the nineteenth century, effective power was in the hands of men probably not less than fifteen years older on the average than in the sixteenth century; and before the twentieth century is out, the average may have risen another fifteen years, unless effective means are found, other than obvious physical or mental decay, to make vacancies at the top. Clissold (in his sixtieth year, he it noted) sees more advantage and less disadvantage in this state of affairs than I do. Most men love money and security more, and creation and construction less, as they get older; and this process begins long before their intelligent judgment on detail is apparently impaired. Mr. Wells’s preference for an adult world over a juvenile, sex-ridden world may be right. But the margin between this and a middle-aged, money-ridden world is a narrow one. We are threatened, at the best, with the appalling problem of the able-bodied “retired,” of which Mr. Wells himself gives a sufficient example in his desperate account of the regular denizens of the Riviera.

We are living, then, in an unsatisfactory age of immensely rapid transition in which most, but particularly those in the vanguard, find themselves and their environment ill-adapted to one another, and are for this reason far less happy than their less sophisticated forebears were, or their yet more sophisticated descendants need be. This diagnosis, applied by Mr. Wells to the case of those engaged in the practical life of action, is essentially the same as Mr. Edwin Muir’s, in his deeply interesting volume of criticism. Transition, to the case of those engaged in the life of art and contemplation. Our foremost writers, according to Mr. Muir, are uncomfortable in the world—they can neither support nor can they oppose anything with a full confidence, with the result that their work is inferior in relation to their talents compared with work produced in happier ages—jejune, incomplete, starved, anaemic, like their own feelings to the universe.

In short, we cannot stay where we are; we are on the move—on the move, not necessarily either to better or to worse, but just to an equilibrium. But why not to the better? Why should we not begin to reap spiritual fruits from our material conquests? If so, whence is to come the motive power of desirable change? This brings us to Mr. Wells’s second theme.

Mr. Wells describes in the first volume of Clissold his hero's disillusionment with socialism. In the final volume he inquires if there is an alternative. From whence are we to draw the forces which are “to change the laws, customs, rules, and institutions of the world”? “From what classes and types are the revolutionaries to be drawn ? How are they to be brought into cooperation? What are to be their methods?” The labor movement is represented as an immense and dangerous force cf destruction, led by sentimentalists and pseudo-intellectuals, who have “feelings in the place of ideas.” A constructive revolution cannot possibly be contrived by these folk. The creative intellect of mankind is not to be found in these quarters, but amongst the scientists and the great modern business men. Unless we can harness to the job this type of mind and character and temperament, it can never be put through—for it is a task of immense practical complexity and intellectual difficulty. We must recruit our revolutionaries, therefore, from the Right, not from the Left. We must persuade the type of man whom it now amuses to create a great business, that there lie waiting for him yet bigger things which will amuse him more. This is Clissold’s “Open Conspiracy.” Clissold’s direction is to the Left—far, far to the Left; but he seeks to summon from the Right the creative force and the constructive will which is to carry him there. He describes himself as being temperamentally and fundamentally a liberal. But political Liberalism must die “to be born again with firmer features and a clearer will.”

Clissold is expressing a reaction against the Socialist party which very many feel, including Socialists. The remolding of the world needs the touch of the creative Brahma. But at present Brahma is serving science and business, not politics or government. The extreme danger of the world is, in Clissold’s words, lest, “before the creative Brahma can get to work, Siva, in other words the passionate destructiveness of labor awakening to its now needless limitations and privations, may make Brahma's task impossible.” We all feel this, I think. We know that we need urgently to create a milieu in which Brahma can get to work before it is too late. Up to a point, therefore, most active and constructive temperaments in every political camp are ready to join the Open Conspiracy.

What, then, is it, that holds them back? It is here, I think, that Clissold is in some way deficient and apparently lacking in insight. Why do practical men find it more amusing to make money than to join the Open Conspiracy? I suggest that it is much the same reason as that which makes them find it more amusing to play bridge on Sundays than to go to church. They lack altogether the kind of motive, the possession of which, if they had it, could be expressed by saying that they had a creed. They have no creed, these potential open conspirators, no creed whatever. That is why—unless they have the luck to be scientists or artists—they fall back on the grand substitute motive, the perfect ersatz, the anodyne for those who in fact want nothing at all—money. Clissold charges the enthusiasts of labor that they have “feelings in the place of ideas.” But he does not deny that they have feelings. Has not, perhaps, poor Mr. Cook something which Clissold lacks? Clissold and his brother Dickon, the advertising expert, flutter about the world seeking for something to which they can attach their abundant libido. But they have not found it. They would so like to be Apostles. But they cannot. They remain business men.

I have taken two themes from a book which contains dozens. They are not all treated equally well. Knowing the Universities much better than Mr. Wells does, I declare that his account contains no more than the element of truth which is proper to a caricature. He underestimates altogether their possibilities—how they may yet become temples of Brahma which even Siva will respect. But Clissold, taken altogether, is a great achievement, a huge and meaty egg from a glorious hen, an abundant outpouring of an ingenious, truthful, and generous spirit.

Though we talk about pure art as never before, this is not a good age for pure artists j nor is it a good one for classical perfections. Our most pregnant writers today are full of imperfections; they expose themselves to judgment; they do not look to be immortal. For these reasons, perhaps, we, their contemporaries, do them and the debt we owe them less than justice. What a debt every intelligent being owes to Bernard Shaw! What a debt also to H. G. Wells, whose mind seems to have grown up alongside his readers’, so that, in successive phases, be has delighted us and guided our imaginations from boyhood to maturity.

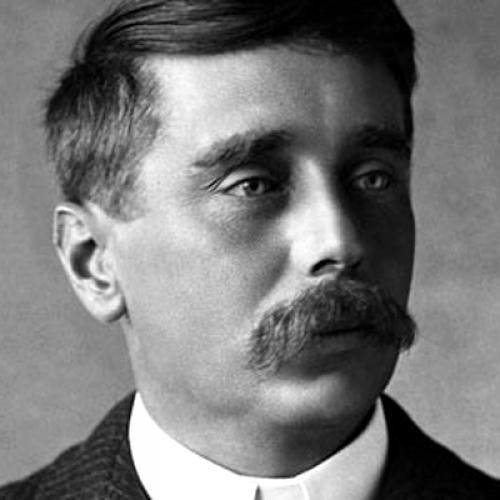

John Maynard Keynes was a British economist whose books include The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money.