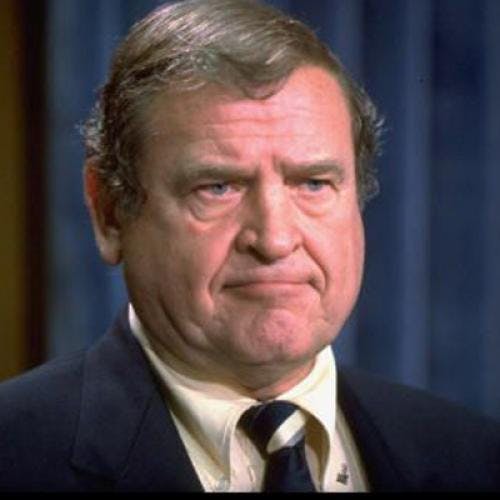

It was a black day in 1985 when Dan Rostenkowski was seduced by respectability. I didn't think so at the time. Like other advocates of tax reform, I was delighted when the chairman of the House Ways and Means Committee abandoned a lifetime of Chicago machine politics and Washington interest group hackery. His famous "write Rosty" TV address, endorsing reform efforts, won him plaudits for his high-mindedness and bipartisanship from which he apparently has never recovered.

Now Rostenkowski stands as perhaps the principal obstacle to Democratic efforts to seize the political offensive with a tax cut for the middle class. He worries that it would be irresponsible, given the deficit He worries mat it might become the occasion for new loopholes. And perhaps he is not as eager as he ought to be, now that he's so chummy with the Republican president, to put his pal on the spot.

Less mysteriously, President Bush is also striking a statesmanlike posture. "I'm not going to jump in and take steps out of some congressional panic," he says in his delightful way. "I will fight against legislation that will … further burden the young people of this country with more and more debt." Further is right. No such statesmanlike concern arose from those quarters over the past decade's tax cuts for the well-to-do.

By now there are so many overlapping tax cut proposals floating around Washington from both parties that it's best to think of them as one big Chinese restaurant menu. Design a meal to suit your own taste.

In column one are the tax breaks themselves. Choose one or more. There's Pat Moynihan's old standby, cutting the Social Security payroll tax. There's a per-child tax credit for families, either refundable to those who don't pay taxes (Tom Downey and Al Gore) or not (Lloyd Bentsen). There's an expansion of individual retirement accounts (Bentsen, various Republicans). And of course there's a tax break for capital gains — either in general (Bush) or in some selective way (various Democrats).

In column two are methods of payment. Choose one. There's raising taxes on the wealthy (Downey and Gore). There's slicing the military budget (Bentsen). Or there's "Put it on my tab" (almost everyone else).

In column three are reasons for the exercise, crass politics apart. Choose any or all. There's reducing the tax burden on the middle class, which is higher now man before tax cutting came into fashion in 1978. There's jump-starting a stalled economy. And there's increasing saving and investment for long-term growth.

So. What shall we have? One problem is that all these dishes take time to prepare and— however delicious going down—time to digest as well. They are unlikely to have any short-term stimulus effect on the economy. This is especially true if they are honestly paid for with spending cuts or compensating tax increases, in which case the net stimulus is nil.

The two proposals aimed at long-term growth—expanding IRAS and the capital gains cut—are both snake oil. IRA contributions are already deductible for most people. The prosperous people who don't now qualify will just take the deduction for money they're saving anyway. The net effect on national savings—after subtracting the cost to the federal treasury—is likely to be negative. And if expanding IRAS did lead to increased savings, that would mean decreased spending—and so much less short-term stimulus. This is the bind a decade of Reaganomics has gotten us into.

The capital gains argument is old and hoarse. The case against a capital gains break, fairness aside, is that the tax code should be as neutral as possible, neither encouraging nor discouraging one form of economic activity compared with others. Let the market work. For that reason, a capital gains cut "balanced" by an increase in the top ordinary tax rate, as some are suggesting, is a particularly foolish combination. What produces tax shelters, empty office buildings, and other economically wasteful activity is the size of the differential between favored and unfavored categories.

Proliferating such categories—which is what various Democratic attempts to "target" a capital gains break would do—is simply an invitation to more shelter malarkey. "New" investments versus "old" investments, long-term versus short-term, investments in this versus investments in that: all such rules presume that the government can outguess the market about what investments will pay off, and that it can outsmart lawyers and accountants who will manipulate such rules to defeat their purpose.

When I was in college there used to be something called "liberal jokes." This was a time, children, when liberals were widely held in contempt from the left. If black activists across the country were screaming "Free Bobby Seale" (an alleged black martyr of the era), a liberal would be someone who proposes the slogan "Parole Bobby Seale." That's a liberal joke. Maybe you had to be there. But my point is that the slogan "targeted capital gains tax cuts"—as proposed by Lloyd Bentsen, Bill Clinton, Mario Cuomo, and other Democrats — is a liberal joke for the '90s.

The only good reason for a tax break now is simply to give a deserved break to the middle class. In a democracy, the fact that this is politically appealing need not be thought of as a fatal defect. Of the two frankly middle-class breaks on the table—a Social Security cut, and a family credit—either will suffice. If your hope is to have some effect on job creation, the Social Security cut is more appealing, since the payroll tax is a direct tax on jobs. On the other hand, families are in political fashion, and the value of the family exemptions has badly eroded over the past few decades. A payroll tax cut would benefit all workers, even those too poor to pay income taxes. To spread the benefits of a family credit similarly would require a complicated rebate arrangement. But, as I said, either will do.

As for column two—method of payment—simply adding to the deficit is clearly wrong. Hoping to pay for a tax cut by slicing defense is also slightly suspect, since everyone knows that defense will have to be cut more than currently planned just to meet current budget targets. And if there is a real peace dividend, either reducing the deficit or spending it on needed government investment might seem a more responsible course. So that logic dictates going for a tax increase on the wealthy.

But there we go, falling into the responsibility trap ourselves. True irresponsibility would be enacting a tax cut that wasn't paid for. Paying for it with revenue from genuine spending cuts that might otherwise be put to a wiser use barely nudges the irresponsibility meter, compared with what Republicans have done during the past decade. Once every ten or twelve years, surely, the Democrats are entitled to indulge themselves.

Agree? Write Rosty.

Michael Kinsley is a former editor of The New Republic and a senior editor for The Atlantic.