This article was originally published on February 16, 1963.

Raise High the Roof Beam, Carpenters and Seymour, an Introduction

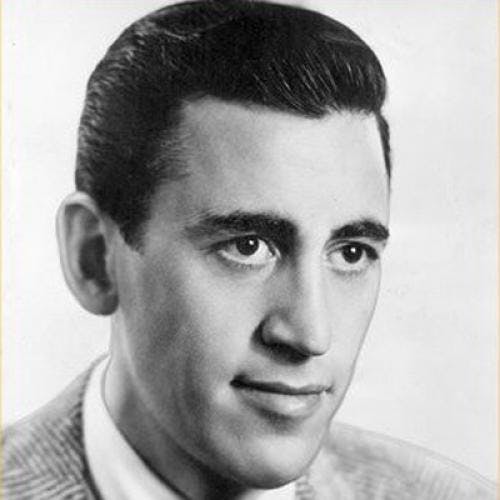

by J. D. Salinger

(Little, Brown; $4)

The chief danger a reviewer has to fight against, in tackling Mr. Salinger's stories about the Glass family, is the temptation to an ungenerous ribaldry. The author lays himself so terribly open; and, of course, since he is a clever man who could be just as cagey as anyone if he chose, this frequent throwing away of defenses has something admirable about it.

The bigger a writer is, the more we put up with his faults, and Mr. Salinger is unmistakably big. In this new book, for instance, he has set himself the task of portraying, or beginning to portray, somebody really good; and since he doesn't believe (perhaps nobody does believe) that you can be good just by being unselfish and decent and keeping the rules, this involves him in drawing a saint, or, in the argot of his narrator Buddy Glass, "a ringding enlightened man." As if that weren't enough, this narrator keeps declaring that he is happy-yes, happy, deeply, even riotously happy. The two most difficult objectives known to man, to describe goodness and to make happiness credible, and Mr. Salinger has undertaken to reach them both at once!

What is more, we trust him to be somewhere on target. He has more intelligence than most writers, and also more feeling. If the two can be run together, there might - just possibly might - emerge, page by page and here and there, a portrait of a good and/or happy man. A real statement of values, living and walking values and not abstractions. So naturally, even though Mr. Salinger has Buddy order us to stop reading if we get bored, we don't leave. We stay, rooted to the spot.

Which is exactly why Mr. Salinger ought to consider us a little. It's the sheerest brutality to treat people badly just because they're not in a position to go elsewhere. Because no one else is offering quite what Mr. Salinger is offering, does that mean we have to put up with slipshod writing? (And it is slipshod writing to give Franny and Zooey that interminable conversation in which he Shows Her The Light: page upon page of essay-material, uneasily broken up by cigarette-lighting. For Chrissake-ing, etc., and finally given a poor little shot in the arm by having Zooey go into the next room and finish the conversation by telephone after an unsuccessful attempt to pretend that he is someone else.) Or soap-opera prattle? ("S. loved sports and games, indoors or outdoors, and was himself usually spectacularly good or spectacularly bad at them--seldom anything in between.") Or a sweat-making dribble of author-comment from the strawfilled headpiece of Buddy Glass? ("I can see, though, that I'm having a little of the usual trouble entailed in trying to make a very convenient generalization stay still and docile long enough to support a wild specific premise. I don't relish being sensible about it, but I suppose I must. It seems to me indisputably true that a good many people, the wide world over, of varying ages, cultures, natural endowments," etc., etc.) Just why should we have to put up with this Ersatz? Does it bring the Glass family more sharply into focus? No. Does it help to put over the perceptions dbout human life that Mr. Salinger is trying to get into our heads? No. Does it irritate hell out of us? Yes.

Let us stand back and recap. Mr. Salinger, as everyone knows by this time, is building up a full-length portrait gallery of a family named Glass, Irish mother, Jewish father. New York habitat, show-biz background, intellectual velleities, numerous and widely dispersed personnel. They are all good people, or perhaps the point is that everybody is good. Anyway, the Glasses have all got religion. The parents, who are uneducated, have it unconsciously, the children consciously. They are looking for goodness and they are not impressed by any secular way of finding it. They are up with Vedanta, Zen, Kierkegaard, Christ, the lot.

An excellent subject. One that fits in very well with the present moment in American life, and therefore has a powerful boost from the Zeitgeist. (All these German words, as always in literary discussion, signal a deep bewilderment. But à nos moutons.)

That bit in parenthesis was suspiciously like the sort of thing Buddy Glass comes out with. I let it stand, but only to show the dangers of the situation. Buddy Glass is the character who stands half-in, half-out of the fable and Tells The Story. Whether the episodes are in the first person singular or not, we are given to understand that Buddy is holding the pen, or at the typewriter. And Buddy is a bore. He is prolix, obsessed with his subject, given to rambling confidences, and altogether the last person to be at the helm in an enterprise like this. A college teacher (that makes the heart sink to begin with), he has a literary reputation about which he is agreeably modest (toothachingly), and, since Seymour committed suicide in 1948, Buddy is, at forty, the eldest Glass child.

I don't like Buddy much. He keeps chewing my ear off about things I don't want to know about. It's all right when he is simply telling a story, as he is in "Raise High the Roof Beam, Carpenters," but when he is just spitballing, in "Seymour — an Introduction," he's insufferable. He can't leave anything out. "Much like a man in a short story called 'Skule Skerry,' by John Buchan, which Arnold L. Sugarman, Jr., once pressed me to read during a very poorly-supervised study-hall period .... " I don't care about Arnold L. Sugarman and I don't want him brought in. Buddy keeps getting postcards from his brothers and sisters, "two of whom, it seems peculiarly worth adding, use ball-point pens." No, it doesn't. It seems peculiarly worth leaving out. A long letter from Seymour to Buddy, quoted in the text, "was written in pencil, on several sheets of notepaper that our mother had relieved the Bismarck Hotel, in Chicago, of, some years earlier." What was the doorman's name? Tell me that or it's no dice - I won't even read the letter.

There I go, falling into the temptation I mentioned at the beginning. The temptation to let go and just horse around (Anglice: act the goat). Don't think I'm not sorry. But how can one help it? This Buddy just cannot be taken seriously. Laughter is all he deserves. Particularly since he is an impostor anyway. He doesn't really exist, and so far from hiding the fact he is in a hurry to say so, to confess that he is really Mr. Salinger with a putty nose on. He keeps mentioning Mr. Salinger's previous work as his own, e.g., "A few years ago, I published an exceptionally Haunting, Memorable, unpleasantly controversial, and thoroughly unsuccessful short story about a 'gifted' little boy aboard a transatlantic liner, and somewhere in it there was a detailed description of the boy's eyes." This story is, of course, "Teddy," and just to stop up the last exit-hole Buddy gives us a quotation from the story, an accurate one. So that all hope of keeping Buddy Glass apart from J. D. Salinger must be abandoned. Mr. Salinger has vanished into his own story. When Buddy Glass says "I" he means Mr. Salinger, who in turn talks about Buddy Glass.as "my alter-ego and collaborator." And so the coy little game of pat-ball goes on, blurring the outlines, importing whimsy where whimsy has no right to be, and generally spoiling the atmosphere of seriousness, unstrained and unpompous but complete seriousness, which a writer like Salinger needs to work in.

One knows, of course, why Mr. Salinger does it - though the explanation doesn't make it any easier to bear. He does it because, like every roman fleuve about a family, the story is obsessive. The much-loved brother who died and yet remains a living presence; the younger sister whom one protects and also learns from: these themes are repeated from The Catcher in the Rye, and the repetition shows how deep and narrow is Mr. Salinger's material. The author himself is hypnotized by his own reveries, so that he sleep-walks into the story and pretends to be Buddy - not only that, but pretends to have been Buddy all the time. Why shouldn't he? Well, the short answer is that being a successful imaginative artist is a matter of being asleep with part of your mind and awake with part of it. In Mr. Salinger's case, the wrong part keeps going under. Perhaps one good shout, from all of us together.... Ready? One, two -