This summer's Philadelphia Eagles training camp was a pretty exclusive affair. The Eagles invited only about 100 people from all of the hundreds of thousands who annually yearn to play pro football. The average male who received an invitation stood six feet, three inches and weighed 230 pounds. Most of the Eagles candidates had played before in the National Football League and on major college football teams. But for every 225-pound monster who received an invitation, a 145-pound weasel was admitted too. Several competitors who did not go to college and others without varsity playing time also found their way into camp. Once there, each player got an equal and objective chance to make the team. The Eagles, a league doormat for ten straight seasons, offer four difficult, but not impossible, ways to find yourself doing toe-touches with 100 other smelly athletes on a miserably hot summer morning at Widener College training grounds.

The first method is least helpful but most realistic: be a professional football player already. The Eagles offered about 40 slots to those who played for them last year. Another half dozen invitations went to those who played for other clubs and were then traded to or released and signed by the Eagles.

The National Football League's annual college draft provides the second route into training camp. The teams take turns choosing players from that year's crop of college graduates. In order to be drafted a player has to get a pro scout to notice him. This can be difficult if you don't play in one of the post-season bowl games or for a name school like Ohio State or UCLA. Before professional football's recent expansion, getting noticed at an obscure football school was almost impossible. Now there is a national syndicate that helps scout players at every school in the country. The scouting organization rates all the players, allowing each team to compare a player at a lesser football school with one at a football power. The Eagles also have two full-time scouts who prowl the nation in search of potential professionals.

The rubric "free agent" covers the rest of this year's invitees. A free agent is a person unaffiliated with a professional team. If he has intrigued the coaching staff, he can sign with the Eagles for a training camp invitation and a small amount of money. Most free agents in the Eagles camp used one of two means to gain invitations. Many in the free agents category have tried and failed with the second route, the college draft. They were drafted by the Eagles or another team within the last few years and later were cut or quit. Undaunted by earlier failure, they have pleaded with the Eagles for another chance.

For those who never have had a chance to play pro football or be drafted, there is still one more avenue open: the Papale method. This path gets its name from a legend in the Philadelphia area, Vince Papale, who never played college football but decided to try his luck at professional football anyway. Several years ago Papale quit his job to start conditioning to be a professional wide receiver. On paper Papale's decision seemed foolhardy. He knew little about football, no more than those who watch it on television on Sundays. His build and speed are not exceptional by pro standards. But he had great determination. He started a series of rigorous workouts. He spent two sessions with The Philadelphia Bell of the now-defunct World Football League, the second session riding the bench. Two years ago he showed up at an annual spring tryout camp, held each year by the Eagles to give athletes overlooked in the college draft a chance to show their stuff. From there he got an invitation to summer training camp. Camp gave him a chance to show what he does best, work with determination. At each round of cuts, week after week, his name came up in coaches' meetings. Each time someone suggested that Papale did not have as much talent as other wide receivers and perhaps should be let go. But each time another coach spoke up in his behalf. He stayed and eventually made the 43-man roster.

A more typical story would be that of Scott Hilton, a 23-year-old carpenter who did not go to college, but who impressed Eagles scouts at this year's spring tryout. His only previous experience was as tight end for the Somerton Stars in the Delaware Valley Semi-Pro Conference. Hilton excelled in the opening days of training camp. After a few weeks, however, he quit. "I simply wasn't mentally prepared," Hilton says now. "I wasn't used to getting up at seven to eat breakfast, getting on the field by nine for a morning workout, stopping for lunch and a nap and then going back on the field again. At night I had to lift weights, study my playbook and make the 11-o'clock bedcheck. I didn't have enough time to study the playbook. 1 just couldn't take it all in. I began to look forward to the nights when I could call home for 20 minutes of relief. It got to be too much mentally."

No matter what path the 102 prospective Eagles used to get into training camp this July, each athlete had one thing in common: he was scared. No one, whether veteran, rookie or free agent, has immunity from the late-night note under the door requesting him to return his playbook in the morning. From the day's first deep knee-bend to the last late-afternoon stride, these would-be professionals were thinking about the cuts the Eagles must make to trim the roster to 43 by opening day.

The Eagles take camp seriously. The team's budget for the month-and-a-half-long affair is more than $500,000. Each day the coach puts the candidates through a series of intensive drills. The daily workouts are straightforward: receivers practice catching passes, blockers throw hundreds of blocks, and quarterbacks hurl balls all day. Records are kept of each player's performances. Typically, a kicker is charted for distance on each kick; a quarterback is measured for accuracy, velocity and quick release. These routines supply the coaches with evidence on which to base their cuts for the first three weeks of training camp, during which time about 30 players are dropped—many because of outright physical or mental mistakes, such as botching passes or blocks or repeatedly running left instead of right.

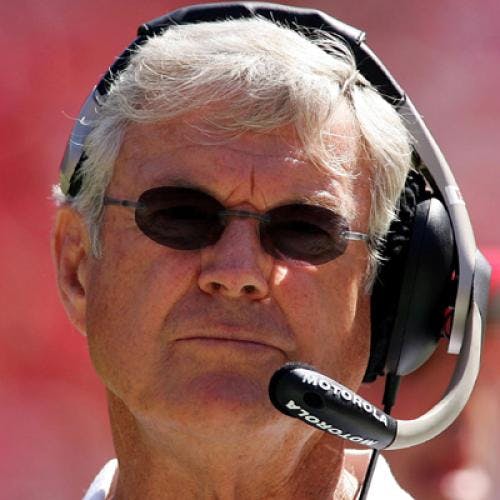

The players cut early gripe the loudest about unfairness. Some, like Wayne Samarzich, a free agent cut after five days of practice, charge that the Eagles cut those who come cheap, like himself, and keep those with big contracts. If a player comes from a school where a coach has contacts or has coached himself, Samarzich says, that helps too. The coaching staff denies such claims of unfairness and points to the elaborate machinery used to make accurate cuts. Assistant Coach Carl Peterson contends that the scrutiny of players at the Eagles camp is fairer and more systematic than in any other competitive profession in the country. No player is cut before 14 judges—one head coach, eight assistant coaches and five personnel representatives—watch him in a full day's worth of practices. The coaches rotate in groups as they watch the players. Insuring that each coach gets a good look. Later at night the coaches look at films of the day's workouts taken from cameras perched to capture every action. Nothing on the practice field is missed, Peterson insists. Each judge must then write a report on each player before a decision can be made. Peterson says there is no room for politics because there are too many people in on the decision, "if a guy wants to complain about a cut, we can show him 4000 feet of practice film showing him why he's been eliminated," he says. This year, as a matter of fact, soon after the lowly Samarzich got the axe the Eagles also sent packing their top draft choice. Skip Sharpe. Sharpe took with him a reported $15,000 in bonus money. Coach Dick Vermeil says he cares so much about fairness that he doesn't like to draft people from UCLA, where he coached previously, because he would overwork them simply to insure that he didn't base his decision on favoritism.

Pro football provides incentives for coaches to be ruthlessly objective in making cuts. There is always another pro coach ready to exploit any misjudgments. Nothing looks worse for a coach than cutting someone who later makes good with a rival team. Still, mistakes can happen. The Eagles thought they had a talented defender when the team used a top draft choice to pick Skip Sharpe. But Sharpe didn't make it past early cuts in camp. Vermeil blames the foul-up on Sharpe's lack of "desire," something that wouldn't show up in the "book" on a player. (The Washington Redskins picked up Sharpe after the cut, but dismissed him shortly before the season began.)

At the end of training camp in September, 14 veterans were no longer wearing the Eagles' green and white because of trades or cuts. Four rookies and five players who came to the Eagles as free agents had survived, out of about 60 who tried out. Were the 43 players wearing Eagles uniforms at the end of the preseason the most talented players who passed through Widener's gates on the opening day of training camp? The jaundiced eye could spot eccentricities in Coach Vermeil's method of selection that might be considered departures from pure meritocratic principles. For example, Vermeil was not terribly fastidious about age discrimination. At the beginning of cuts, he called eight-year veteran running back Art Malone the best blocking back in the National Football League. The next day Art Malone was cut. Vermeil said that if an older player and a younger player are equal, the older player would be let go, because the younger player has more promise of becoming great.

Vermeil also has a weakness for flamboyant displays of enthusiasm and "hustle." ("Desire," "performance," "heart" are also among his favorite catchwords.) The player who stays down longest on his toe touches, who doesn't cheat in sprints, who gets excited and hollers in drills, gets the edge in Vermeil's book. Some players who didn't excel in the drills or the pre-season games were kept, perhaps partially because they used to run laps when they weren't called for, an action that fits Vermeil's definition of hustle.

Nevertheless, if a keenness for young blood and an overindulgence in rituals of enthusiasm are the only departures from a purely meritocratic selection procedure, and if Coach Vermeil's summer camp is typical of the way things work in the National Football League, then professional football compares rather favorably as a meritocracy to fields of endeavor where much more is made of it and where the process of winnowing goes on for years rather than for six weeks. The rigid and lengthy credentializing process for medicine allows no alternative routes for late starters, no matter how talented or eager. Would a top Washington law firm ever find room for a Vincent Papale who had gone to an obscure night school (or had trained himself)?

The reason the Eagles must keep themselves open to potential talent, no matter how eccentric the route by which it comes to them, is that the team itself is involved in a pretty schematic meritocratic struggle each season. The coaches must choose the best because if they don't the team will lose football games. And if that happens, the coaches will be fired. That's why meritocracy works in the National Football League.