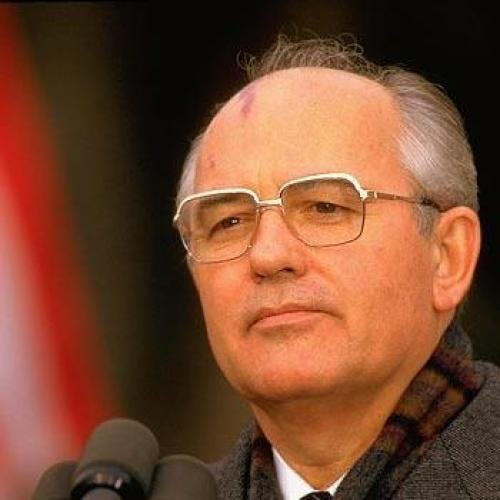

The cheer with which Western commentators greeted Mikhail Gorbachev’s tease that the Berlin Wall might come down “when the conditions that generated the need for it disappear” is another sign of how credulous we have become in receiving blandishments from Moscow. It is not only that Gorbachev categorically denied that the Wall “was a result of an evil intention.” He also asked us to acknowledge that conditions in 1961 justified its erection. More than that: since those conditions still exist today, the Wall remains a legitimate expression of policy, even a necessity.

It’s important to remember that the Wall was built to imprison people who wanted to live elsewhere, and who were wanted elsewhere. Those were, and still are, the specific conditions to which Gorbachev obscurely alluded. But what lay behind those conditions? Certainly not a fact of nature or an unavoidable circumstance. The three million refugees who left prior to August 13, 1961, were not escaping simple adversity. They were fleeing what their successors persist in wanting to flee: Communist rule imposed by the Red Army of the Soviet Union. These are conditions that Mikhail Gorbachev could have a decisive hand in changing. But won’t.

Who knows how many more would have fled if they had known that the Soviets would soon construct an impenetrable physical divide between what they used to call “the puppet Bonn regime” and their own satrapy to the east? The allure of exodus was a standing reproach to the doctrine and power of every Communist state: in the Soviet Union itself, throughout Central and Eastern Europe, in Cuba and Vietnam and China (and Nicaragua), and, as in Hong Kong, wherever the specter of Communist rule cast a shadow. The desire of millions to flee, and the fact that hundreds of thousands risked their lives in order to leave, were as close as these societies ever came to a true plebiscite of the popular will. People really voted with their feet. Locked in by the Wall, escapees became ever more audacious in their escape routes. Some crashed through checkpoints; others flew over the Wall in hot-air balloons.

To the East Germans this desperation was especially galling. After the Second World War, when German nations exiled by Nazism had a choice of two Germanys to which to return, it was the Communist East that claimed to attract the more idealistic and the more humane. Bertolt Brecht used to explain that the choice was akin to that of the doctor with two syphilitic patients--an old lecher and a pregnant prostitute--but penicillin enough for just one. He would choose Communist Germany, the putative pregnant prostitute, over the incorrigibly authoritarian West Germany. Such mawkish simplifications could not survive the crush of events. The brutal suppression by tanks of the workers’ rising in East Berlin in 1953 provoked even from the dependable Brecht that devastating epitaph. The government has lost its confidence in the people, he noted.

Would it not be easier / In that case for the government / To dissolve the people / And elect another?

Many of the returnees went west, following the furtive tracks of simple folk.

The Wall, even more than the ongoing repression, was a confession of Communist defeat. It was the contrivance of Nikita Khruschev, the previous Soviet reformer, a way of addressing the crisis of disenchantment with communism. Perhaps it is understandable that Gorbachev, who has put himself against so much in the Soviet past, should be reluctant to admit the obvious about this especially telling symbol of the Party’s failure to win, except through terror, the loyalty of the very people in whose name it ruled.

Despite the tense atmospherics over the Berlin question that preceded the construction of the Wall, no pundit or position paper, as Adam Ulam pointed out later, had foreseen it. Still, no one was surprised. After all, Khruschchev already had on his ledger far bloodier deeds, the bloodiest of which was called to mind during Gorbachev’s visit to Bonn. While the present Soviet leader told his unaccountably ecstatic hosts that he was not yet ready to dissolve Khrushchev’s Berlin enormity, in Budapest the Hungarians were retrieving from unmarked graves and reinterring the remains of the murdered victims of the 1956 Soviet invasion. The West had been checkmated, just as it would be in Berlin.

This funeral drama may augur the restoration of the rudiments of Hungarian national independence, but it is sobering to recall that it has taken nearly 35 years for Hungarians to begin to think that their country again might be their own. Analogies are not analyses. But how long will it take before Chinese masses feel confident enough, or brave enough, to challenge Party orthodoxy again? And is not President Bush’s squeamishness about the events in Beijing the sign of yet another checkmate?

A Hungarian writer, reflecting on the Budapest tragedy ten years later, argued that what was at work then (and during “Polish October”) was an insurrection of the elemental, “the resurgence of fundamental aspirations, like the need for fraternity, equality, genuine, authority, liberty, and above all, most frequently, the need for truth.” It was, in its way, a romantic, even naïve revolt--from its youthful mystique of a re-created but organic community to the grave pronouncement by Imre Nagy, the long-time Communist turned revolutionary prime minister, that Hungary henceforth would be a neutral party in the competition of the great powers.

Hungary was not rewarded for its exhilaratingly dumb courage. On the contrary, Eisenhower and his otherwise routinely belligerent secretary of state, John Foster Dulles, acceded to the Russians’ rout of freedom. There was handwringing and some rhetorical pretense, but little more. The Hungarians had believed implicit American promises (and some earlier, more explicit ones, too) that we would come to their aid. But as a Hungarian student poet wrote some weeks later:

To the West

You still want to come?

Too late, too late.

We are cut and fallen

Like wheat in the reaper…

We know from Tocqueville that tyrannies are in danger when they ease their vigilance. The Polish stirrings and the Hungarian revolution, pursuing the lead from Mother Russia, followed a period of de-Stalinizing reforms in both countries. But it took us a generation to learn that tyrannies are in danger whether they ease their vigilance or don’t. A boot stamping on a human face will not always command obedience; it will only rarely result in efficiency or productivity; it will never issue in initiative or daring for official ends. That is why communisms in power are ultimately forced to seek compromises with popular sentiment. It is why Deng Xiaoping made concessions to the market idea. But in China now, as in Hungary in 1956, the concessions demanded are so fundamental as to be intolerable to the authorities. Tanks are the preferred alternative.

So it is not merely a lack of material well-being that has been eating away at communism for decades, corroding the mobilized enthusiasms of the propaganda state. People don’t take great risks or die for a trade-off. What animated the streets of Budapest in 1956, the shipyards of Gdansk in 1980, and Tiananmen Square this year was the idea, so long derided in Marxism and at many American universities, of “bourgeois” liberties. These are the formal codified rights from which genuine obligations derive. They include centrally the right to oppose and to persuade others to oppose. What’s more: the right to have that opposition count and be counted. This means a free press and, in our time, access to high technologies of information and communication. It means elections. Don’t be surprised if it also comes to mean everywhere a multiparty political system--the entire panoply of Western political institutions, and the Western idea as well of civil society altogether independent of politics.

This is not what Gorbachev intends. It explains his lapidary comments on Chinese developments: he daren’t tempt the citizens of Moscow to mount the kind of peaceful mass protests launched and put down in Beijing. It is also only one reason he won’t pull down the Wall. He is as afraid to let the people of East Germany choose as is Erich Honecker. Inevitably, now, the choice there would be for a wholly new social contract, a democratic social contract.

There is, alas, no prudent way for the West to provide any of the peoples in Soviet orbit with an immediate opportunity to make that choice. But our diplomacy should be geared to hastening the time when they will be able to do so. We haven’t even been assertive in pushing bilateral talks with the hard-line governments of the now fragile Warsaw Pact. In fact, the present behavior of most of the NATO allies, not least the Germans, is likely to encourage Gorbachev and his comrades to believe that they can get Western aid and Western trade without great reciprocal measures in the currency of freedom – especially in those countries (the GDR, Czechoslovakia, Bulgaria) whose leaders are still reflexively faithful to Soviet power. Increased economic and political contact between West and East is important, but is hardly a sufficient purpose of a democratic foreign policy. If that is all it amounts to in the end, it would be tantamount to another betrayal of freedom’s martyrs. We’ve done that often enough.