I’m driving on the 10 freeway cutting west when the call comes. “Hello,” a voice says, before misgendering me with an honorific. “This is a courtesy call from the Los Angeles Passport Agency … I’m calling to let you know that we can’t process your passport application.” The voice is telling me that I will not be able to pick up the passport with an updated gender marker that I am currently driving to pick up. “New rules from the top,” is how he puts it.

It is January 24, 2025. Four days after Trump retook office—and one day, it seems, since the last possible moment for a non-cisgender person in Los Angeles to get a passport that accurately matches their identity. I hang up the phone as I pull into the Los Angeles Passport Agency, a drab modernist tower just off the freeway. I collect myself, and my documents, and head inside.

It’s not that I hadn’t seen this coming. I had been working to avoid this very outcome for months, knowing the Trump administration would make getting this passport much harder. Yet still I became, as far as I know, the first person rejected by the Los Angeles Passport Agency under the new administration’s policies.

When you decide that you want the state to recognize your gender as something other than what you have been previously known, it’s not like there’s a single office or even website that will tell you the protocol. You are on your own. If you’re trying to change your legal name at the same time, it adds additional levels of complexity. The full process varies by state, by identity document, and in some cases, the state in which you were born (presuming you are a U.S.-born citizen).

For my particular case, it took two full weekend afternoons of research before I figured out my pathway: (1) Get a new state ID with same name and updated gender. (2) Get a court order from California to have my original birth certificate and Social Security card “sealed” and new ones issued—something my birth state will do, but which many do not. (3) Use new birth certificate and Social Security card to obtain a new passport with updated name and gender marker. (4) Use new passport to obtain a new driver’s license and REAL ID with updated name. You can see that there’s a circularity to the paperwork process here, which, in this case, requires me paying for a driver’s license twice.

But then, in December—as we were all staring down the barrel of the imminent Trump presidency redux—I attended a know-your-rights workshop at a queer bar in my neighborhood. I learned that I had been thinking about this paperwork ordeal much too simply. The organizers told me that if I wanted an update to the gender marker, I did not have time to wait for a court order and a name change. Rather, we should presume Trump’s very first day in office—January 20—is the deadline to get any gender marker updates done. The organizers advised that I should update my legal pathway by obtaining a new passport with the old name and new gender marker immediately (cost: $190, not including $31.40 for second-day air shipping of the paper application), and then ditto for state ID ($36), then getting the court order to submit for the new birth certificate and Social Security card with updated name and gender ($450). Then, I should use the above documents to get another passport ($190), this time with updated gender and new name, and use the second new passport to get yet another state ID ($36), and real ID ($30).

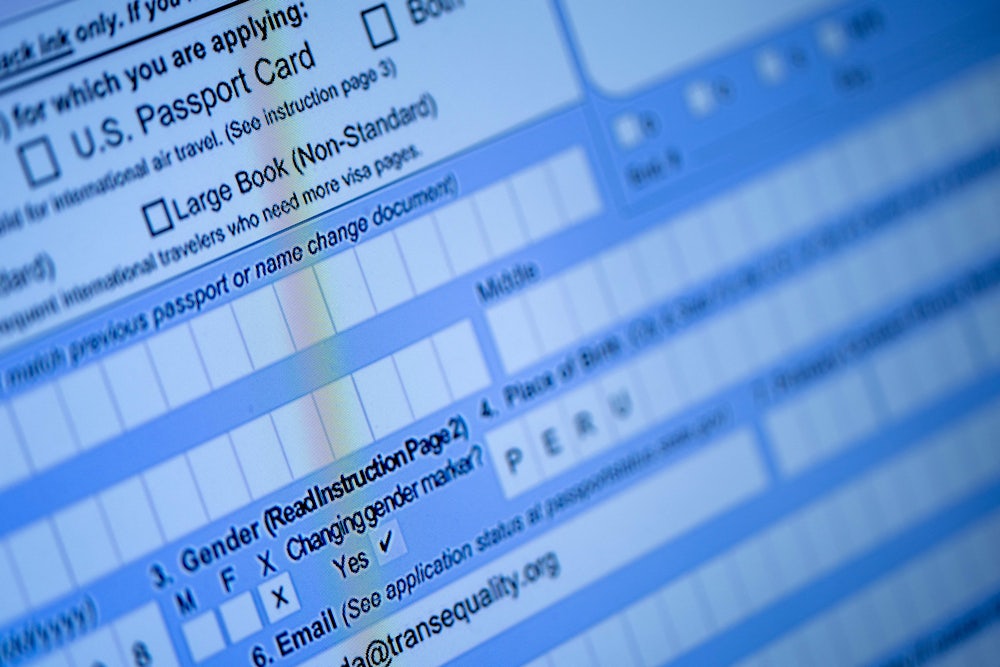

I got the driver’s license with a new gender marker quickly—Californians are privileged that this process is very straightforward and does not require any supplemental legal or medical documentation. The passport application, though, put me at an impasse. The form wanted to know, Why is the applicant updating gender? Is it (A) to correct a mistake, or (B) to affirm lived gender?

I hesitated. I have enough friends who work in government to know that behind any one of these forms is a spreadsheet with sortable columns; I didn’t like the idea that a malicious technocrat could just right-click and “sort by transgender.”

I checked “(B) to correct a mistake.” Besides, I thought … it’s not not a mistake. I paid the rush delivery and express processing. I waited.

The new year came, and with it, a package from the Passport Agency. I ripped open the envelope and found … my old passport, completely unchanged. An accompanying letter explained, in so many words: We looked into it and found no mistake, here’s this back. I was stunned, although I later learned that trying to check the “mistake” rather than “transgender” box is a well-known mistake within the official-gender-marker-changer community. At any rate, my $190 was not returned.

The date was January 5, which gave me exactly 14 days to get this done before Trump took office. Even with priority service, there wasn’t enough time to process it through mail. The only option was to go to a passport agency in person.

But a new hurdle: You can only get an in-person appointment at the passport agency if you have an international flight booked within two weeks. So once again, I pulled out my credit card and bought the cheapest refundable international ticket I could find ($250). And with that flight confirmation, I snagged the very last passport appointment before the end of the Biden administration, on January 17, at the crack of dawn. I took a big sigh of relief. This is going to work.

The morning that the Santa Ana winds started picking up, it was a hot, gusty, pleasant day. Then, Los Angeles County was on fire—an epic disaster that would kill 30 people and displace 150,000. Anyone who didn’t lose their home, it seemed, knew at least a few people who did.

Sometime in between scrambling to make myself useful to several newly homeless friends and other local mutual aid efforts, I got a text from the L.A. Passport Agency saying that my appointment had been canceled. The edge of the biggest fire, in Malibu, was just seven miles from their office, and they were shutting down until further notice.

I called the federal passport hotline, and an agent gave me a choice of an appointment on January 19 in San Francisco or an appointment on January 22 in Los Angeles—presuming that the office reopened by then. I started doing math in my head. San Francisco is almost 400 miles from L.A.—either a grueling road trip or yet another plane fare. Plus, I’d need a place to stay while the passport processed. So it was that, or take the January 22 appointment two days after Trump’s inauguration. Would that be OK? How much could he possibly do in two days?

I opted for January 22 on my home turf.

Two days after Trump’s inauguration, I went to the Passport Agency and gave them a new application for a passport with a new gender marker—this time, checking the box to update gender identity.

I asked the clerk whether this was still allowed. Would this work? He told me yes, and that I could come back on Friday to pick up my passport. I swiped my card for another $190.

Two days later, I was driving back to the Passport Agency when the phone rang. The new passport would not be ready for me after all. “New rules from the top,” the official told me.

Merging onto the 405 freeway, I channeled my inner Karen, my inner I Would Like to Speak to the Manager. “There’s really nothing I can do,” he responded. “I’m just calling you as a courtesy.…” I dug deeper, conjuring my inner shtetl immigrant. My inner What Would You Do If You Were There Then.

“Sir, I—”

“You’re calling me ‘Sir,’” I said, trying to stay calm. “You realize why I’m applying for this change, right? You realize what this is about?”

“Ma’am, sorry. We can’t process your application. New rules from the top.”

“You have the printer in your office. You can just print it.”

“Anything we print we have to—”

“You have the power to just print it.”

“We can’t.”

“People are going to get killed because of this.” I let that hang heavy for a moment. “This is going to kill people. You realize that, right?”

Neither of us said anything for a long time, the car silent but for the 405 traffic.

“Sir—sorry, Ma’am—I’m sorry, but we can’t process your application.”

I hung up just as I pulled into the Passport Agency parking lot. After going through security and a long wait, eventually, I came face to face with the voice from the phone. He was not malicious or unkind—he actually seemed like a nice guy: the kind face of a faceless bureaucracy. He told me I could either take my old passport back, or they could process a new one but with the same gender marker on it. Could I at least get my $190 back? I could not. Contact your Congress person, he said.

All told, I had spent $446.76 and countless hours on this process, not including the $250 that I wound up not being able to get back from a supposedly cancelable flight, and still didn’t come away with a new passport. I have put my name-change paperwork on hold indefinitely.

I returned home to see my social media feed blowing up with Marco Rubio’s order to halt all passport applications requesting a gender marker change, or an X marker. As I read through other first-person accounts, it occurred to me that I may be one of the lucky ones: At least I got my passport back. At that same Passport Agency just a few days later, a woman named Mary Fox wasn’t able to get a passport with either gender marker. As she tells it in in the video (which currently has 1.2 million views), Fox agreed to receive a passport with a “male” gender marker on it, only to be told, “We won’t be able to give you that either. We won’t be able to give you any passport. We have no further information.” Fox said she continued seeking clarification but was forced to leave under threat of arrest. “They are effectively banning me from travel, even though they will not call it a travel ban,” Fox said. In a subsequent post, Fox stated that she did eventually receive a passport (albeit with an “M”), and wondered whether that was due to the media attention her story had accrued.

Fox’s account is just one of many circulating around the trans internet. In Chicago, one woman alleges that the Passport Agency confiscated her passport when she wasn’t even trying to update her gender marker—she was only trying to update her name. “They said that since I changed my name legally they cannot return it to me, with either my true name and gender, or my deadname and gender, or any combination,” she wrote on Reddit.

Another account in Boston describes a passport applicant receiving a passport with the wrong gender—and a gash on the front of the booklet so big that it might render the document useless. Photos show that the applicant’s supporting documents—a birth certificate and documentation of legal name change—were returned with damage that suggested malicious intent. One document was ripped, the other burned. Massachusetts Transgender Political Coalition issued a statement condemning the incident.

While not all of these accounts are confirmed, there is a chilling effect on the trans community and their families. One mom in the Midwest told me that passport worries are causing her nonbinary teen to question whether they’ll be able to study abroad this summer; they don’t know what will happen when they try to get their first passport when their birth certificate has a gender marker of “X.” A different mom in the Bay Area told me that her family canceled an international trip because of her child’s “X”-gendered passport. That mom also gave up a major freelance project because her client, an old friend who knows her kid, turned out to be a fervent supporter of Trump and Elon.

Here in L.A., a good friend told me they felt forced to skip a trip to Florida for the wedding of their mom and stepfather—a destination, mind you, still within the U.S. Florida already has laws on the books such that it is illegal to have a gender marker on your ID other than your assigned sex at birth. Just being in Florida with this sort of passport, my friend fears, could be a chargeable offense.

The vagueness of Marco Rubio’s January 23 decree freezing all “X” passport applications and gender updates creates a vast uncertainty in high-stakes situations. How is a law enforcement official ordered to respond to people Traveling While Trans? And regardless of orders, how will they act? The chaos, like the cruelty, seems to be the point.

In the absence of any concrete understanding about what is happening to our country, it’s hard to keep from fear-spiraling myself. Currently, my primary fear-spiral is that airports begin having TSA run bathroom patrols, checking IDs as people queue up to pee. Airports are federal property; would committing the “crime” of going to the “wrong” bathroom be a federal offense? Punishable how? Would trans people be allowed to leave the country? Would we be allowed to return?

Like a lot of American Jews who lost family in Hitler’s Europe, I grew up obsessed with the Holocaust. I’d read Lois Lowry and Elie Wiesel and think to myself, Why didn’t they just leave? In the weeks and days before Trump 2.0, I started wondering whether those of us in the trans community will eventually ask ourselves the same question: Why didn’t we just leave then? And now, I wonder, with our freedom of movement in precarity, whether it’s already too late.

A week after my visit to the passport office, they sent me an automated email inviting me to take a survey. They asked me to consider a statement: This passport application experience increased my trust in the U.S. Department of State to work for U.S. citizens. On a scale of one to five, the survey asked, how much did I agree with this statement?