Last Friday, the first wave of Brazilians deported from the United States since the inauguration of Donald Trump arrived in the Amazonian city of Manaus. Images of passengers deplaning in handcuffs and shackles, as well as allegations of inhumane treatment, caused an uproar over the weekend in the political discourse of Latin America’s largest nation. Entering the U.S. illegally is, after all, not a crime in Brazil.

The flight was part of a bilateral agreement between the U.S. and Brazil, signed in 2018, aiming to expedite the deportation of Brazilians held in U.S. immigration detention centers. In 2021, after reports that Brazilians were being handcuffed during deportation flights, the Brazilian government requested a review of the procedure by U.S. authorities, including then–national security adviser Jake Sullivan and former Secretary of State Antony Blinken. Brazilian officials note that the U.S. has a standard procedure of using handcuffs during the boarding of deportees while still on American soil.

However, the use of handcuffs during the flight is recommended only if there is a risk to the passengers or crew. At the time, Brazil’s foreign minister warned that if the request was not addressed, the Brazilian government could refuse to allow deportation flights to land in the country. As a result, standard practice has been to limit the use of handcuffs to the interior of the aircraft and only when necessary for flight security.

So far, the center-left government of Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva has taken a cautious approach in dealing with the new Trump administration. Some on the left sought a stern rebuke from Lula, but the Brazilian president does not seem eager to pick a fight with Trump so early into his second term. Brazilian diplomats have reportedly been instructed not to respond to Trump’s provocations but to firmly yet discreetly seek clarifications regarding the treatment of Brazilians in U.S. custody.

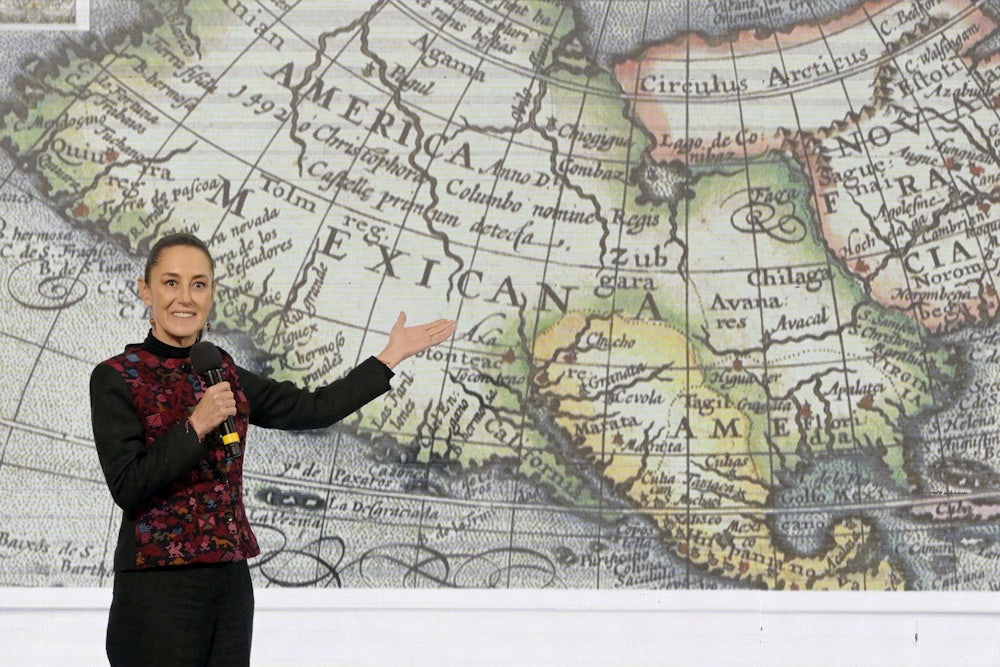

This weekend’s events came on the heels of a phone conversation between Lula and Mexican President Claudia Sheinbaum, in which the two leaders “reaffirmed their commitment to fostering productive relations with all countries in the Americas, including the new U.S. administration, with the goal of preserving peace, strengthening democracy, and promoting regional development,” according to an official release. Reading between the lines, the heads of the two Latin American giants are huddling to strategize over how to react to Trump. Indeed, one unintended consequence of Trump’s return is that Mexico and Brazil are likely to enjoy warmer relations than they have in generations.

Colombia, for its part, took a different approach. On Sunday, Gustavo Petro, Colombia’s first-ever left-wing president, denied landing permission for two U.S. military planes carrying deportees. Predictably, this prompted a harsh response from Trump, who threatened sanctions against Colombia, including a 25 percent emergency tariff on Colombian goods set to double in a week, travel bans, and revocation of visas for Colombian officials. Petro retaliated by announcing similar tariffs on U.S. products and stated that Colombia would only accept deportees aboard civilian flights, ensuring their humane treatment. He offered to send the presidential plane to pick up Colombian citizens in the United States.

Petro, the ex-mayor of Bogotá and former guerrilla fighter, also took to social media. In a long post on Twitter/X that recalled a distinctive Latin American essayistic tradition, he seemed to invite political tension with the U.S. president. “Trump, I don’t really like travelling to the U.S., it’s a bit boring,” he began, before noting his appreciation for the Black neighborhoods of Washington D.C., Walt Whitman, Paul Simon, and Noam Chomsky, as well as Sacco and Vanzetti, the Italian immigrant anarchists controversially convicted of murder and executed in Massachusetts in 1927.

“So, if you know someone who is stubborn,” he continued, “that’s me, period. You can try to carry out a coup with your economic strength and your arrogance, like they did with [Salvador] Allende. But I will die in my law, I resisted torture, and I resist you.” His conclusion was tense, epic, and uncompromising: “FROM TODAY ON, COLOMBIA IS OPEN TO THE ENTIRE WORLD, WITH OPEN ARMS, WE ARE BUILDERS OF FREEDOM, LIFE AND HUMANITY. I am informed that you impose a 50 percent tariff on the fruits of our human labor to enter the United States, and I do the same. Let our people plant corn that was discovered in Colombia and feed the world.”

Many Latin American leftists expressed their admiration for Petro’s intransigence on social media even if, notably, heads of state kept quiet. In a matter of hours, however, his manifesto was rendered moot. “The Colombian government reports that we have overcome the impasse with the United States government,” read an official communiqué issued on Sunday evening, adding that Colombia’s foreign minister would be traveling immediately to Washington for “high-level meetings.”

For its part, the Trump administration and its supporters at home and abroad were eager to celebrate Petro’s supposed retreat. The White House’s own statement did not mention any forthcoming meeting with Colombian officials, instead glibly asserting, “Today’s events make clear to the world that America is respected again. President Trump will continue to fiercely protect our nation’s sovereignty, and he expects all other nations of the world to fully cooperate in accepting the deportation of their citizens illegally present in the United States.”

For now, temperatures have cooled. It remains unclear what political price the already-unpopular Petro will pay domestically for standing up to Trump with so much righteous indignation only to stick a muddled, premature, and inconclusive landing. The principal takeaway from this incident, however, is that there is currently no clear coordinated strategy among Latin American leaders to deal with Trump’s disruptive nature.

The new U.S. president has rekindled a belligerent interventionism in the hemisphere that has lurked beneath the surface of U.S.-Latin American relations since the end of the Cold War. But there is more of William McKinley and Teddy Roosevelt to Trump than Kissinger and Nixon when it comes to the Western Hemisphere. So progressive Latin American leaders are faced with the challenge of pushing back against late nineteenth-century tactics from Washington in a twenty-first century defined by deep political polarization online and off. In an attempt to dispel the confusion and discuss what is to come, the Community of Latin American and Caribbean States on Sunday night called an emergency meeting to be held on January 30.

Ultimately, there may prove to be too many issues dividing Latin American governments for close coordination with regard to the United States to come to fruition. As such, individual reactions will remain central to the course of hemispheric relations. Trump toadies like Argentina’s Javier Milei might be thrilled by the MAGA redux, but it is not clear that blanket subservience to the United States is a winning political project anywhere in the hemisphere. For its part, Brazil has its own cards to play. On Monday morning, Lula just happened to have a phone call with Vladimir Putin to, as he put it, “discuss issues on the global agenda and between our countries.”

By reanimating an unsubtle brand of U.S. imperialism, Trump is almost certain to heighten the appeal of U.S. rivals on the world stage. Latin Americans are reasonably concerned with their own self-interest in pursuit of reliable trade partners with something appealing to offer rather than the type of imperial hubris expressed by conservative journalist T. Becket Adams, who in response to Petro’s gambit tweeted: “Oh, wait. Right. We’re the United States. We can just DO stuff when 3rd-worlders try flexing on us.” Despite nostalgic MAGA delusions, the global unipolar moment is fading rapidly—if it hasn’t passed already. The Western Hemisphere is not a passive mass of U.S. subjects, a canvas onto which Washington’s raw power can be projected without challenge. If a clenched fist is all the United States extends its neighbors, many, including Latin Americans themselves, might find they stand to benefit from recoiling.