It’s impossible to say whether Donald Trump or Kamala Harris will win the presidential election next month. Far more easy to predict is that there will be litigation after Election Day over the results. By one count, there have already been more than 130 legal challenges to election laws across two-thirds of the states. Trump and his allies are aggressively sowing doubt about the election results so that they can create fraudulent slates of electors to deadlock the Electoral College if he loses.

In some ways, the American electoral system is more resilient now to Trump’s malfeasance than it was four years ago. Democrats hold key gubernatorial and election offices in Arizona, Michigan, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin, providing a backstop against GOP skullduggery. Congress passed a law after the chaos of the 2020 election to clarify the Electoral Count Act of 1887. Storming the Capitol to stop the count on January 6, 2025, will also be far more difficult with a Democratic president in the White House.

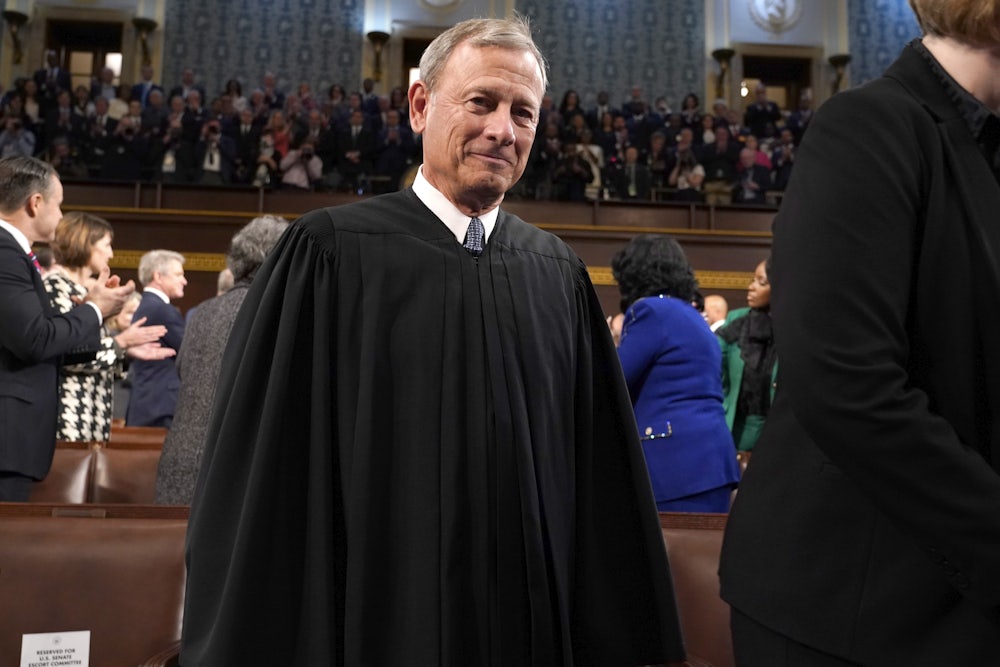

But there is one powerful actor in the presidential election that still keeps me up at night: the Supreme Court. I was fairly confident ahead of the 2020 election that the justices would not grossly intervene for Trump’s benefit. Indeed, they ultimately rejected MAGA litigation intended to throw out the results, wholesale. But the court’s rulings in Trump’s favor last term—first on disqualification under the Fourteenth Amendment and then on presidential immunity—mean I can’t make the same assumption this time.

For most of the Trump years, the Supreme Court did not show the former president any clear favoritism—by which I mean that its members did not rule in his favor in ways that did not reflect their general approach to the law. When the justices tossed a series of congressional subpoenas for Trump’s financial records in 2020, for example, it fit within the court’s general trend of insulating the executive branch from congressional scrutiny. That same day, they also allowed New York prosecutors to obtain those records with a grand jury subpoena, rejecting his sweeping arguments for immunity.

This trend continued through the end of Trump’s presidency as the justices consistently rejected his last-ditch legal attempts to overturn or change the election results in 2020. The Supreme Court even rejected a bizarre but well-organized lawsuit by Texas and other Republican-led states that sought to negate the electoral votes in multiple states that President Joe Biden had won, without hearing arguments on it. Eleventh-hour pleas to specific members of the court like Justice Samuel Alito also went nowhere.

Something has changed since then. In the disqualification case, the court’s conservative majority went out of its way to butcher Section 3 of the Fourteenth Amendment in Trump’s favor. The unsigned majority decision declined to hold that Trump hadn’t taken part in an insurrection or that the clause didn’t apply to him, which would have been narrower (albeit flawed) grounds for reversal. Instead they took the sweeping position that states couldn’t enforce the disqualification clause without separate congressional authorization. The conservative majority, parting ways with the liberal justices, then went one step further to hold that federal courts could not disqualify Trump either.

As I’ve noted before, the Anderson ruling was a judicial train wreck. It defied the normal practice for how presidential qualifications are enforced. States routinely reject candidates for not meeting the age or natural-born citizenship requirements. It also mangled the structure of the Fourteenth Amendment itself. Not only is the clause self-executing in both design and practice, but requiring congressional action also complicates how the rest of the amendment works. Taken altogether, the ruling smacked of short-term expediency and political convenience instead of thoughtful judgment.

Trump v. United States is much worse. Here we must begin by stating the obvious: There is no such thing as “presidential immunity” in the American constitutional order. It cannot be found in the Constitution’s text, history, or tradition. The Supreme Court had never before suggested that presidents enjoy any form of criminal immunity before now. Even American presidents didn’t think it existed until Trump proposed it. If they did, Gerald Ford wouldn’t have bothered to pardon Richard Nixon after he resigned over Watergate.

To accept the idea of presidential immunity is to defy the fundamental principles of the Constitution. The Framers abhorred corruption and abuse of power, which they saw as inherently dangerous to republics and the principal historical causes of their demise. When describing the presidency in Federalist No. 69, for example, Alexander Hamilton defended the new office from its critics who saw creeping monarchism in its creation. He reassured readers that the president would not be a king, by emphasizing that he would be bound by the law.

“The President of the United States would be liable to be impeached, tried, and, upon conviction of treason, bribery, or other high crimes or misdemeanors, removed from office; and would afterwards be liable to prosecution and punishment in the ordinary course of law,” he explained. “The person of the king of Great Britain is sacred and inviolable; there is no constitutional tribunal to which he is amenable; no punishment to which he can be subjected without involving the crisis of a national revolution.”

Roberts’s ruling made no mention of any of this. He instead expounded upon a dividing line between official acts and unofficial acts based on a framework he conjured out of thin air. “There is no immunity for unofficial acts,” the chief justice stated. When it comes to “official acts” that involve a “core constitutional power” of the presidency, a current or former president has “absolute” immunity. For everything else, Roberts claimed, a president has “presumptive” immunity that could be reviewed by future courts.

How did Roberts justify this? He drew from a hodgepodge of sources to make his argument. Some of it comes from the court’s prior separation of powers and executive privilege rulings, which are stretched beyond recognition to make an argument for immunity that their authors did not consider or embrace. Other sources are almost insulting to the reader’s intelligence. Roberts quoted Federalist No. 70 for the proposition that the Framers envisioned a “vigorous” and “energetic” chief executive, even though Hamilton was simply arguing for a singular president instead of a multimember executive.

Perhaps the most risible citations are to United States v. Nixon. That 1974 case effectively ended Richard Nixon’s presidency by forcing him to obey a grand jury subpoena for the Watergate tapes. Though the court’s ruling emphasized that no man was above the law and rejected Nixon’s claims of “absolute immunity,” Roberts read the decision’s language on executive privilege as tortured evidence for presidential immunity.

None of this is remotely persuasive. The Framers were more than capable of saying whether federal officials had any form of immunity. They happily did so in other circumstances. Under the Constitution, members of Congress enjoy a limited form of legislative immunity that is narrowly tailored to their official duties. They cannot be arrested while traveling to and from sessions, nor can they be punished for what they say during speeches and debates.

Federal and state judges also have what is known as judicial immunity. The Constitution makes no explicit mention of it, but judicial immunity is typically seen as a bedrock feature of the common-law legal system that Americans inherited from England before 1776. English judges have had some form of protection from litigation over their rulings and official acts since the Plantagenets.

What Roberts articulated for presidents goes far beyond these forms of immunity as well. A senator who takes envelopes of cash in exchange for specific votes on legislation can be tried and convicted for bribery. So could a federal judge who demands kickbacks from litigants in exchange for specific rulings. The Supreme Court has often narrowed anti-corruption cases involving “unofficial acts” but had typically held the line when it comes to “official acts.”

Not so when it comes to presidents. Here the formula is now reversed: If a president acts corruptly when carrying out an “official act,” he is automatically above the law. Only when he acts unofficially is he subject to the general criminal laws of the nation. Even the carve-out for unofficial acts is little reassurance because the president can simply comingle his unofficial acts with official ones to provide himself with legal cover.

Part of the special counsel’s indictment of Trump, for example, focused on his interactions with Justice Department officials. After Election Day in 2020, Trump and his allies pressured the acting attorney general and other top officials to publicly endorse his false claims of election fraud. Their goal was to build support for state legislatures to create fraudulent slates of presidential electors under the false premise that the election results were tainted.

Challenging one’s own election results is not a core presidential power or even a peripheral one. In Roberts’s eyes, however, using those conversations as evidence for a criminal case would be unconstitutional. “The indictment’s allegations that the requested investigations were ‘sham[s]’ or proposed for an improper purpose do not divest the President of exclusive authority over the investigative and prosecutorial functions of the Justice Department and its officials,” he wrote. Justice Sonia Sotomayor, writing in dissent, found that reasoning ridiculous. “If that were the majority’s concern, it could simply have said that the Government cannot charge a President’s threatened use of the removal power as an overt act in the conspiracy,” she wrote. “It says much more.”

Roberts’s overall dismissiveness of Sotomayor’s dissent only revealed the weaknesses in his own argument. “True, there is no ‘presidential immunity clause’ in the Constitution,” he wrote. “But there is no ‘separation of powers clause’ either.”

If someone had leaked the immunity decision, à la Dobbs decision, and it had contained this line, I would have written it off as a forgery. Even if one sets aside the logical flaws in that reasoning, there is still a glaring factual error. There are, in fact, three separation of powers clauses in the Constitution: the three vesting clauses that begin Articles 1, 2, and 3. That Roberts somehow forgot this—or ignored it in favor of a weak zinger—typified his approach to the case.

Even within the conservative majority, there were efforts to temper the extremism of Roberts’s ruling. Justice Amy Coney Barrett took a much narrower approach in her concurring opinion. She rejected the court’s framing of the issue as one of “immunity,” instead focusing on whether presidents could challenge the constitutionality of specific criminal laws as applied to them before trial. Barrett concluded that a president (or former president, in this case) could lawfully bring such a challenge, which would be evaluated on a case-by-case basis.

“The Court describes the President’s constitutional protection from certain prosecutions as an ‘immunity,’” she wrote. “As I see it, that term is shorthand for two propositions: The President can challenge the constitutionality of a criminal statute as applied to official acts alleged in the indictment, and he can obtain interlocutory review of the trial court’s ruling.”

This framework is somewhat more defensible. If a particularly tough-on-crime Congress passed a law that made it a federal crime for a president to issue a pardon, for example, that would raise serious separation of powers concerns. Barrett raised a hypothetical situation in which a hostage-rescue mission might violate a real federal statute that makes it illegal to conspire to commit murder in a foreign country. Sotomayor’s earlier reference to the removal power could also fall under those terms.

“If the statute covers the alleged official conduct, the prosecution may proceed only if applying it in the circumstances poses no ‘danger of intrusion on the authority and functions of the Executive Branch,’” she wrote, quoting from a previous Supreme Court ruling. This approach is not without its own shortcomings—it is still fairly deferential to presidents and leaves open plenty of questions about when and how they can be prosecuted. Barrett did not write comprehensively on this since her opinion was only a concurring one. Had she written the majority opinion for the court under this framework, the damage done would have likely been far less grave.

Roberts’s errors are so fundamental that they force us to reevaluate both him and the court itself. It is worth emphasizing that the conservative justices in the majority abandoned all of their previously stated beliefs to write this decision. Michael Rappoport, a University of San Diego law professor who serves as the director of its Center for the Study of Constitutional Originalism, described the decision as an “originalist disaster.” Other nonliberal legal commentators noted that Sotomayor’s dissent was far more faithful to the original public meaning of the Constitution.

But this is not merely about disagreements in interpretive method or judicial philosophy. Those happen all of the time. This is about basic understandings of the American republic and its civic tradition. Roberts’s ruling comes from a world without John Locke, without Montesquieu, without Thomas Jefferson or James Madison or Alexander Hamilton. He describes a Constitution unmoored from republican virtue and higher principles of self-government. If living constitutionalism is French and originalism is Italian, then Trump v. United States is written in Klingon.

To make matters worse, the outcome appears to have been unavoidable. The New York Times reported in September that Roberts had brushed aside efforts from the start to reach consensus from the liberal justices, instead favoring a divisive, maximalist ruling that gave Trump almost everything he wanted. Sometimes the court’s most flawed rulings are the product of the fragmented consensus that is required to form a five-justice majority. Not so in this case. The blame lies squarely on Roberts—the chief justice, the heresiarch, the balls-and-strikes umpire who happily gave Trump four outs and loaded the bases.

That brings us back to the 2024 election. If Harris wins a majority of electoral votes next month, I have no doubt that Trump and his allies will ask the courts to intervene on his behalf or force others to go to the courts to stop him. He is eagerly laying the groundwork to do it as we speak. Twelve months ago I would have assumed the Supreme Court would resolve those cases with the same equanimity and skepticism that it showed—and that Trumpworld’s efforts deserved—in 2020.

Trump v. Anderson and Trump v. United States make it impossible to maintain that certitude. The court’s conservative majority eagerly abandoned text and precedent to clear Trump’s path to run in this election and to shield him from the consequences of trying to overthrow the last one—and they did so at a time when they were freed from any real pressure, political or otherwise, to show him deference. I am no longer confident that they would brush aside fraudulent slates of electors or compel MAGA-friendly officials to certify legitimate election results. I can no longer assume that even the most ridiculous legal theories will be rejected out of hand. After all, “absolute presidential immunity” used to be one of them.