Keith Haring is to art what “Happy Birthday” is to the American songbook: a standard whose ubiquity hasn’t quite dulled its ritual magic. Since his death in 1990, Haring’s iconography—radiant crawling babies, barking dogs, three-eyed faces, rubbery bodies that are busily alive—has colonized vast swaths of cultural real estate. Has the work of any recent American artist been so relentlessly hawked? Haring is practically a public utility at this point. There are Haring mugs, T-shirts, sneakers, and tote bags; Haring bathrobes, rugs, pillows, and prayer candles; Haring playing cards, chess sets, yo-yos, and ice cream flavors. (The inventory includes curiosities such as sex toys and dog chews.) “The greatest thing is to come up with something so good it seems as if it’s always been there, like a proverb,” the poet Rene Ricard wrote of Haring. The next greatest thing is to come up with something so universal it can be sold anywhere.

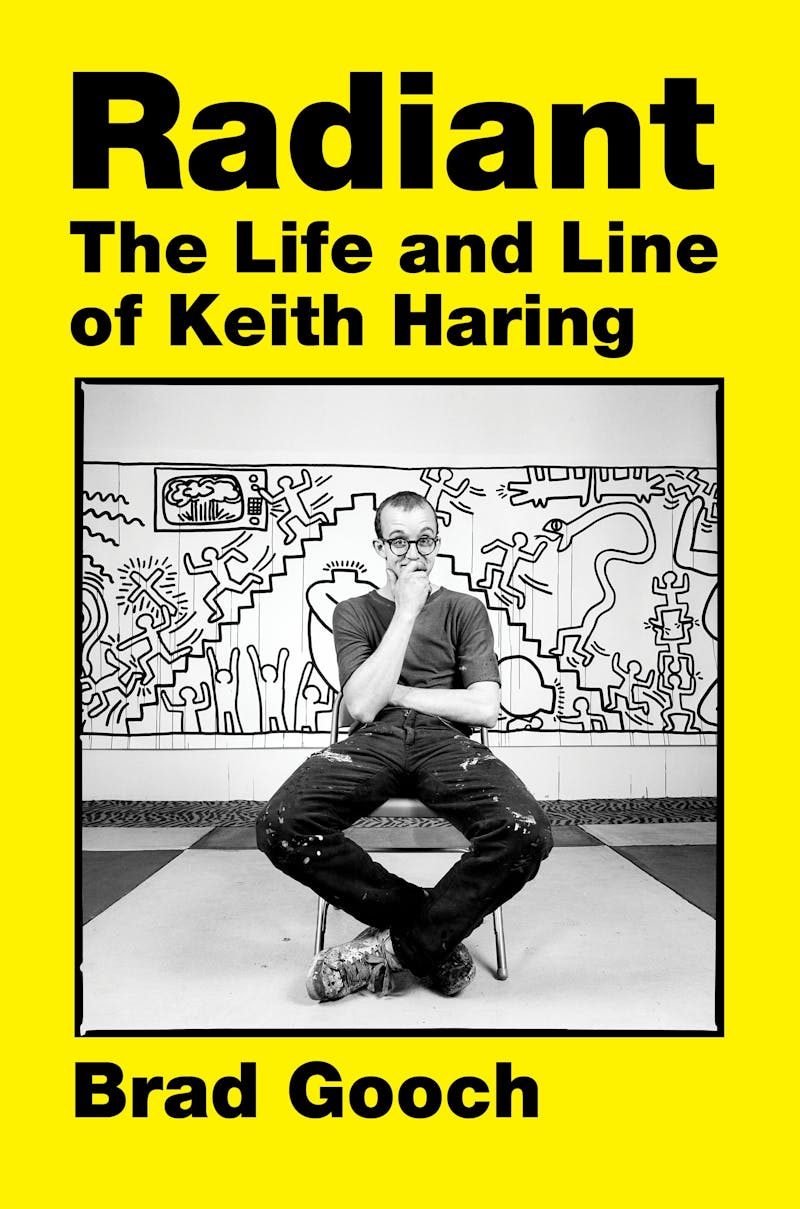

In Radiant: The Life and Line of Keith Haring, Brad Gooch delivers not only a biography of the artist but a globe-trotting account of how Haring’s pictograms flooded the zeitgeist. These stories are inseparable but distinct. I must confess: Haring the protagonist isn’t all that fascinating. Likable, yes, but nice guys make for dull company. When contrasted with Andy Warhol (neurotic, bewigged) or Jean-Michel Basquiat (enigmatic, doomed), Haring comes off as pleasantly mild. Aside from a few middling contretemps with his lovers, he was mostly drama-free: a congenial, earnest, and hardworking man. He adored children. He liked dancing on Saturday nights. Sex was his sport.

Haring’s art is a different matter. Even when he was alive, his work had its own virality. In 1980, he began what Gooch calls “one of the largest public art projects ever conceived”: more than 5,000 chalk drawings hurriedly improvised on blank advertising panels throughout the New York City subway system. This graffiti—fugitive glyphs from the political and psychic doomsday aboveground—made Haring a local cause célèbre. (“He received nearly one hundred summonses during the entirety of the subway project, but also a few arrests,” Gooch writes.) The drawings jump-started his fame, and for the next decade Haring was the wunderkind of a new sensibility that distilled hip-hop, advertising, fashion, and nightlife into highly marketable commodities.

The critic Vivien Raynor described Haring as “an artist nobody doesn’t love.” And Haring’s own credo was to make “art for everybody,” which was both an aesthetic and commercial imperative. In 1986, he opened the Pop Shop in SoHo, selling branded merchandise in a savvily art-directed environment that mimicked a fast-food drive-through. (A second, short-lived outpost opened in Tokyo two years later.) Haring described the venture as an “extended performance,” and, in fact, his whole career fits under that umbrella in a way only Warhol rivals. The subway drawings were as much a public ceremony as an art intervention; their evanescence was part of what made them talismanic riddles. Haring’s friend, the photographer Tseng Kwong Chi, shuttled around the subterranean city documenting the works before they vanished, as if they were already relics.

Haring was reluctant to decipher his own symbolism. His statements often consisted of canned populist rhetoric (“art for everybody”) or vaguely woo-woo sentiment (he referred to his images as “primitive code,” akin to automatic writing). Because his personal life was largely stable—Haring had neither the fatal dependencies of Basquiat nor the harrowing childhood of David Wojnarowicz, for example—the complexities of his bio aren’t so much psychological as vocational. Radiant is really the story of a career, of one artist’s entanglement with the market. Haring made no masterpieces per se, only a repertoire of communicable figures and stylistic trademarks. If you want to understand why that repertoire electrified viewers and emptied wallets in the 1980s, and why it continues to do so at a gallop, you won’t necessarily find the answer in a book about Haring’s day-to-day life. He was right when he called himself just a “middleman” for his work. He needed his art more than it ever needed him.

Aside from a brief religious infatuation and victimless teenage rebellion, Haring’s early years were boilerplate. Born in 1958, he grew up in small-town Pennsylvania, the oldest of four children whose first names all began with K. His father, an electronics technician and amateur cartoonist, introduced him to Dr. Seuss and Walt Disney. Haring was already obsessed with drawing by the time he entered kindergarten. TV was another constant: cartoons, sitcoms, and The Monkees were his mainstays. In 1972, 14-year-old Haring joined the Jesus movement after hearing a “tall Black man” espouse the virtues of personal salvation at a March of Dimes walkathon. This evangelical honeymoon lasted about a year and primarily consisted of Haring plastering fluorescent “One Way” stickers—the calling card of Christ’s suburban publicists—all over town. He also doodled religious symbols in a foretaste of the crucifixions and irradiated crosses that haunt his later work.

In a reversal of the usual order, Haring found drugs after religion. First came marijuana, and then a bedroom diet of quaaludes, barbiturates, speed, and PCP. A rendezvous with LSD when he was 15 or 16 induced a creative breakthrough: “I started doing stream-of-consciousness drawing and shapes melting one into another.” Haring trumpeted an acidhead philosophy in which chance plays an outsize role in life and art; in interviews a few years later, he paraphrased Louis Pasteur’s paradoxical aphorism, “chance favors the prepared mind.” For the rest of his life, Haring drew or painted freestyle, and almost never made preparatory sketches, even when embarking on jumbo public murals. The occult coherence of the line was his new faith.

After high school came a period of expeditions both literal and existential: art school in Pittsburgh, cross-country travels, Grateful Dead groupiedom, stilted relationships with girls, stifled crushes on boys. Haring discovered the work of Jean Dubuffet, whose deliberately crude figuration and vehement endorsement of untrained and institutionalized artists were touchstones. He read The Art Spirit, the 1923 treatise by painter Robert Henri, which declared art “the province of every human being”—an idea Haring finessed into his own anti-materialist ethos. Likewise, the Belgian painter Pierre Alechinsky was a revelation, with his impulsive line work and gestural fluidity. After seeing an Alechinsky exhibition at the Carnegie Museum of Art in 1977, Haring resolved to ditch Pittsburgh and make his fortune in what he called “the center of the world.”

No biography really begins until its subject moves to New York. Gooch sketches a city that was sweltering and bombed-out, Technicolored with graffiti. Haring saw traces of the artists he admired in this rogue street language with its cartoonish forms and bulbous lettering. He saw, too, hints of Japanese and Chinese calligraphy. The downtown poetry scene became another novel intoxicant; William S. Burroughs’s cutup technique and fractured language excited Haring.

But art always came first. Haring curated shows at Club 57, a basement nightspot in the East Village. Among his exhibitions were works by anonymous makers and one of erotic art. “Some of the most interesting, most inspiring and influential art I have seen in the last two years in New York City has been on the street,” he wrote, heeding the example of Dubuffet’s egalitarian eye. “Many of these things remain untouched, undocumented, perhaps un-noticed.”

What was being noticed was the emerging art scene on the Lower East Side. Some of the most vivid writing about Haring’s work comes not from Gooch (whose prose follows the neutral tone of most contemporary biography) but from the critics he cites. William Zimmer of the SoHo Weekly News apprehended the tension underlying many of Haring’s scenes, a kind of combustive energy that’s simultaneously panicked and jubilant:

The human figures on his posters, based on the international symbols employed in airports, do unspeakable things. But because they are faceless, near-automatons, their functions don’t seem to arise from their own desires. One rutting couple might claim, “UFOs made us do it.” Along with the humans are dolphins, our would-be boon companions and rivals in intelligence. Haring provokes the question: what is willed and what is reflex?

Elsewhere, the actress Ann Magnuson recalls what it was like to encounter Haring’s “personalized petroglyphs that spelled relief from the piss-soaked wreckage of the Lower East Side.” Gooch recounts the giddiness of Haring’s subway era when the artist “often finished thirty or forty [drawings] in a three-hour shift, with no possibility of revising, as erasing created a cloud of a smudge.” Haring debuted several signature motifs, including flying saucers (perhaps a nod to having recently seen Forbidden Planet), figures with holes gored through their stomachs, and teased snakes. Once, when Haring was drawing the latter on the Grand Central Station platform, a bystander rushed over to exclaim, “I hear ya. We’re all getting swallowed up by some fuckin’ snake!”

As Haring’s star ascended, so did his romantic life. He fell in love with Juan Dubose, a Black deejay he met at a bathhouse. “He’s totally butch and it’s the best sex I ever had,” Haring said. The couple set up house together and became fixtures at Paradise Garage, a dance club in the West Village that catered to Black and Hispanic patrons. One clubgoer remembers a dance floor so sweat-slicked it had to be dusted with baby powder. Music was the lingua franca at the Garage; the video for Madonna’s “Everybody” was filmed there in 1982, just before she became indomitable. Ingrid Sischy, then editor of Artforum, likened Haring’s discovery of the club to Gauguin landing in Tahiti.

Around that time, Haring also began collaborating with Angel Ortiz, a 14-year-old Puerto Rican boy better known by his graffiti tag LA II. “I’m sure inside I’m not white,” Haring confided in his journal. His relationship to nonwhite culture was sincere, but tinged by inevitable hierarchies and imperceptions. While many of his works promulgated activist messages—he denounced apartheid in South Africa and painted a visceral commemoration of Michael Stewart, a Black street artist who died after being brutalized by police in 1983—Haring sometimes indulged an appropriative impulse. (Keith Haring’s Line: Race and the Performance of Desire, by the scholar Ricardo Montez, examines these dynamics in a more rigorous, albeit academic, way than Gooch’s book does.) In 1984, a Haring mural in Melbourne, Australia, was vandalized after critics accused the artist of pilfering aboriginal imagery. “I didn’t even know what Aboriginal art was,” Haring said in self-defense.

Bill T. Jones, the Black choreographer whose nude body Haring famously painted in 1983, noted that Haring “loves people from a class lower than his own” but seemed incapable of meeting the emotional demands of such a disparity. Haring and Dubose separated in 1985, partly because Dubose was using heroin and cocaine. He’d “lost his soul somehow,” a friend said, and was just “Mrs. Keith Haring.” In short order, Haring found solace in Juan Rivera, a 28-year-old Puerto Rican man (“a walking sex object,” per Haring) who worked odd jobs. Their relationship burned out in 1988, when Haring pursued his final and most unlikely conquest: a straight, 19-year-old Puerto Rican deejay named Gil Vazquez. The couple jetted around Europe in a sexless romance that puzzled some of Haring’s friends, and will likely puzzle many readers.

By the mid-’80s, Haring’s productivity was in overdrive. He signed with Tony Shafrazi, a gallery owner whose maverick reputation included spray-painting KILL LIES ALL across Picasso’s Guernica at the Museum of Modern Art in 1974—a stunt for which he was arrested. Haring was “a perfectionist as far as his career went,” according to another onetime agent, and deeply enamored of fame. “It has been moving so quickly that the only record is airplane tickets and articles in magazines from the various trips and exhibitions,” Haring wrote in his journal in 1986. “Someday I suppose these will constitute my biography.” The more hectic Haring’s career becomes, the more Gooch’s book hyperventilates into glorified itinerary—a haze of trans-Atlantic flights, luxury hotels, big commissions, and famous names. Among the most notable is Warhol, with whom Haring maintained a reverential friendship and, at least from Warhol’s side, a kind of muffled envy. After attending the closing of a Haring exhibition in 1984, Warhol lamented in his diary: “... I got jealous. This Keith thing reminded me of the old days when I was up there.”

Warhol’s most enduring lesson for Haring was the concept of business art. “During the hippie era people put down the idea of business,” Warhol wrote. “They’d say ‘Money is bad’ and ‘Working is bad,’ but making money is art, and working is art—and good business is the best art.” Haring’s Pop Shop literalized Warhol’s philosophy while also further tarnishing his reputation among critics who weren’t favorable anyway. “Maybe if he had been able to open a shop from the start, we wouldn’t have had to deal with him as an artist,” Hilton Kramer groused. The confluence of capitalist mass production and the rarefied preciousness of art disturbed many old-guard tastemakers. It also alienated some of Haring’s fellow street artists. In 1983, a Haring mural in the East Village was defaced with graffiti reading BIG CUTE SHIT and 9,999, a reference to Haring having told The Village Voice that he’d cap his prices at $10,000.

Haring’s legacy remains as much about branding and economics as art. When the Financial Times asked last year, “HAVE WE REACHED PEAK KEITH HARING?,” the question missed the point of Haring’s retail saturation: The peak is the whole shebang. Pervasiveness is proof of concept. Art is for everyone.

“I went over to the East River on the Lower East Side and just cried and cried and cried,” Haring wrote after he was diagnosed with AIDS in 1988. The art he made during his final two years includes some of his most provocative and renowned works, such as Once Upon a Time, the orgiastic black enamel mural in the men’s room of what is now The Center in the West Village. Gooch describes its “entangled penises, cum shots, and avid, flicking tongues” as a “sex-positive paean to a golden age of promiscuity.” Haring also created vibrant agitprop for ACT UP. In 1989, he printed 20,000 copies of his poster Ignorance = Fear, which featured a trio of faceless yellow figures pantomiming see no evil, hear no evil, speak no evil. Privately, Haring admitted, “I really want to ... try to heal myself by painting. I think I could actually do it.” He died in the early morning hours of February 16, 1990.

Haring has now been dead longer than he was alive. What can we say of him more than 30 years later? Gooch’s book offers private marginalia: Haring was a lifelong list-maker; white Casablanca lilies were among his favorite flowers; he requested that his final bedroom look like a “whorehouse.” But about Haring’s art, inscrutability still prevails. His work came quickly, instinctively, discharged from whatever collective unconscious he channeled. His images call to us because they’re legible despite their mysteries, and somehow joyful, even when we don’t know the meaning of that joy or understand its costs. His figures, too, are anonymous but specific in ways we all recognize: Here is heartache; here is life. Haring conveys the vulgarity of simply being in the presence of effervescent art—that desire to gorge, to stare. And he knew his own power. “I am making things in the world that won’t go away when I do,” he wrote. “But now I know, as I am making these things, that they are ‘real’ things, maybe more ‘real’ than me, because they will stay here when I go.”