Ali Zaidi, the White House’s thirtysomething national climate adviser, stood before a lectern in a packed conference hall at the NYU School of Law wearing a crisp navy suit, a blue tie, and just enough stubble to look roguish and anti-establishment but not slovenly. It was September 18, day 2 of Climate Week NYC, and Zaidi was in town to tout the administration’s environmental accomplishments. He began by highlighting the critical role the nation’s youth, like the law students arrayed before him, were playing in the climate movement. “It’s really been the voices of young people who have organized and agitated for change—” he was saying when audience member Sim Bilal, 21, rose to his feet.

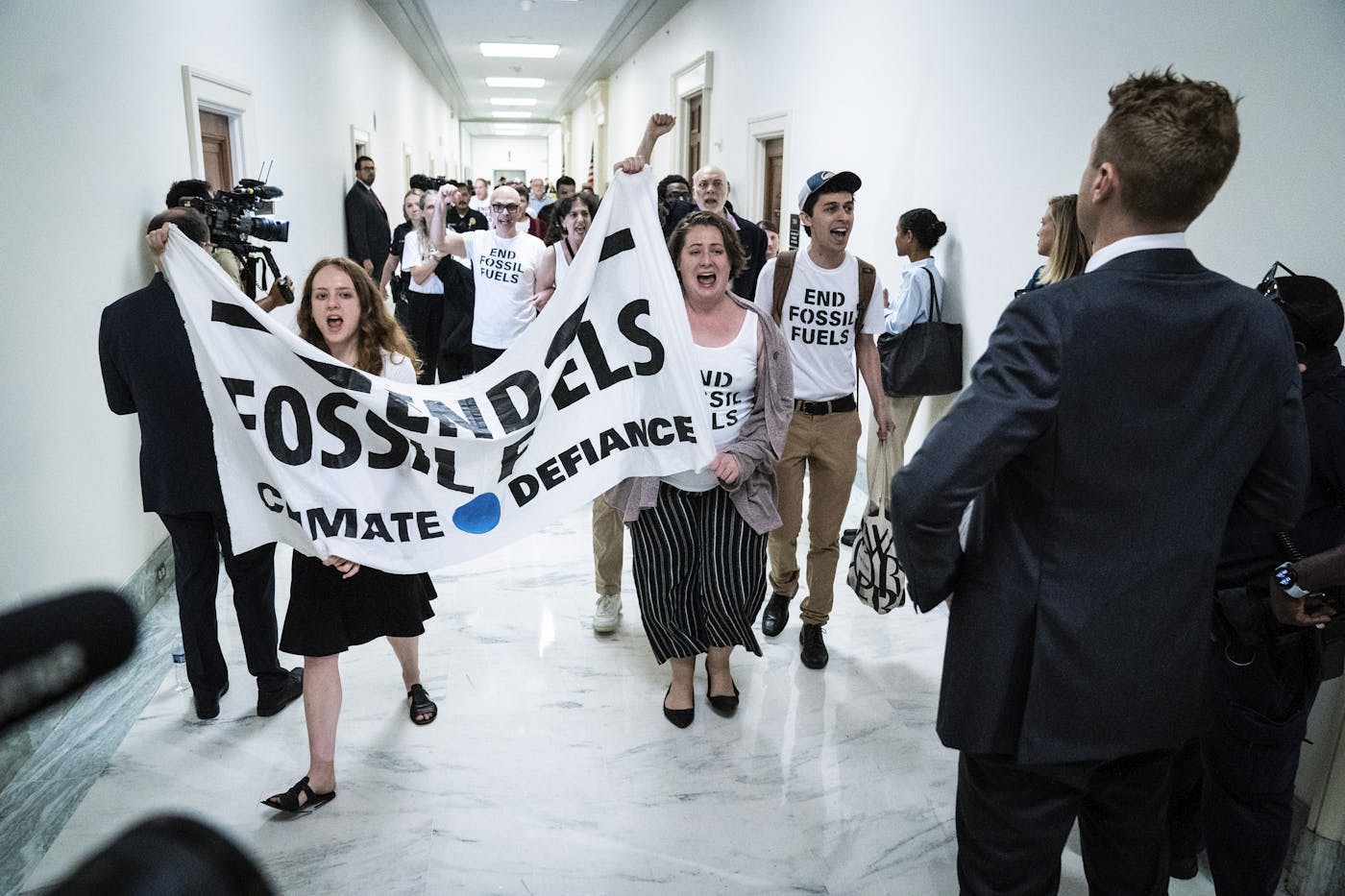

A member of the newly launched pressure group Climate Defiance, Bilal, an L.A.-based community organizer, wearing a black watch cap and an overstuffed backpack, had come to make his own voice heard. He was young. He was agitating.

“Will you publicly ask Biden to oppose the Willow project?” he demanded, referring to ConocoPhillips’s plan to drill for oil in a 499-acre patch of Alaskan tundra. “You guys have protected 13 million acres of the Arctic, but that’s not enough. So, yes or no?”

Zaidi, impressively unfazed, thanked him for the question. “As you noted, the president has taken historic action to conserve public lands, and he has really advanced climate action that I think reflects the energy and organizing of young people, as well as others who have pushed for urgent climate action, and translated that into the single largest legislative win on climate and...”—the answer went on and on, rhetorical rope-a-dope of the highest order. Caught off guard by this hypnotic monody, the heckler appeared stunned into silence.

Then another protester sprang from his seat. “Will you cancel Willow, yes or no?” he shouted. As half a dozen additional protesters popped up in the audience and unfurled a banner, a look of defeat crossed the official’s face. The chant rose up: “Hey Ali! Get off it! Put people over profit!”

It was just one small scene during an action-filled week that featured dramatic protests from numerous groups, including various Sunrise Movement hubs and Extinction Rebellion chapters, the Youth Climate Finance Alliance, New York Communities for Change, Declare Emergency, Planet Over Profit, Stop the Money Pipeline, and the Climate Organizing Hub. Hoping to better understand the movement’s goals and strategic thinking as a momentous election looms on the horizon, I shadowed protesters as they blockaded the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, shut down the Museum of Modern Art (Marie-Josée Kravis, wife of fossil fuel investor Henry Kravis, chairs the board), and infiltrated a Broadway for Biden fundraiser featuring Lin-Manuel Miranda and Sara Bareilles. But it was the relentless bird-dogging of Ali Zaidi—the NYU action was the fourth time he’d been targeted by Climate Defiance this year—that best illustrated one of the central dilemmas facing the movement as it stirs itself from a pandemic-induced slumber: To bury Biden or to praise him?

As the commotion continued at NYU, Zaidi dashed from the stage, exiting not via the main entryway but through a service door—a maneuver that went unchallenged by his antagonists, save one. When his prey fled down a flight of stairs into the building’s basement, Climate Defiance’s 30-year-old founder, Michael Greenberg, his sneakers still damp from the rain-soaked Fed protest earlier that day, was right behind him.

In theory, all of these people are on the same side. They all “believe the science.” They think drastic action is needed, urgently, if we’re to keep the average warming below 1.5°C, as will be necessary to avoid the worst effects of an overheated atmosphere. These are not the “climate criminals”: the fossil fuel profiteers, their paid lobbyists, or their media enablers, nor even the social doyennes who married them.

Even those determined to face the problem head-on, though, fall into two camps, which sometimes, as at NYU, find themselves in conflict. Call them the schemers and the dreamers. The schemers are adherents of political pragmatism, would-be masters of the inside game. They’re realists, technocrats. They believe in vote-counting, win-wins, committee markups.

The dreamers have a more expansive view. They contend that nothing short of a wholesale reinvention of our economy and way of life will meet the moment. They view the schemers’ stubborn “realism” as tragically naïve in its own way. Because, dreamers will tell you, the magnitude of the problem is so vast, its implications so dire, and the required solutions so radical that dadsplain-y appeals to the art of the possible are just another flavor of “soft denial.”

By virtue of his senior White House role, Ali Zaidi can safely be pegged as a schemer. Michael Greenberg, like most of his comrades—young couch-surfers, who travel by Megabus and subsist on vegan sushi and canned black bean soup—is a dreamer. Of course, these categories are flexible. Nobody exists solely within one camp. Zaidi no doubt has a bit of dreamer about him; Greenberg is a hell of a schemer, as his group’s rise to national prominence just months after its first action amply illustrates.

Many advocates oscillate between these paradigms as circumstances dictate. For instance, Al Gore was once as capable a spokesman for the dreamer perspective as we’ve seen. “We must make the rescue of the environment the central organizing principle for civilization,” he declared more than three decades ago (gulp) in his book Earth in the Balance. But Gore was also part schemer, copping in the same volume to his own “tendency to put a finger to the political winds and proceed cautiously.” As he told author Bill McKibben back in 1992, with customary Spock-like detachment, “The maximum that is ... politically imaginable right now still falls short of the minimum that is scientifically and ecologically necessary.”

The earth’s average temperature has risen by more than half a degree in the ensuing years, and political imaginations have been forcibly widened along with it. Some of Biden’s sharpest critics concede that the Inflation Reduction Act’s $369 billion bequest to the clean energy revolution represents a significant achievement. Among other things, it pours $60 billion into the development and manufacture of solar panels, batteries, and other green technologies; boosts tax credits for electric vehicles and rebates for home energy upgrades; and spends $20 billion encouraging more sustainable agricultural practices (though so far nobody wants to touch the third rail of climate politics: forswearing meat and dairy). The White House estimates that the combined effects of the legislation will slash greenhouse gas emissions by 41 percent below 2005 levels. (That said, a 30 percent decline was apparently happening anyway, based on preexisting trajectories.) Biden has also taken concrete steps by way of executive action: He rejoined the Paris Agreement, canceled Donald Trump’s oil leases in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge, declared 10 million acres off limits to future drilling, and announced the establishment of a Civilian Climate Corps.

Perhaps just as important is how the IRA flung open the Overton window on the purposeful use of government spending to improve people’s lives and reshape markets, a window neoliberals of both parties (including Gore) have been inching shut since the 1980s. And because it was designed to sprinkle government largesse far and wide, the IRA could also turn out to be a political masterstroke, handing Democrats a legitimate climate success story with which to rally voters for the 2024 contest. It has already made things awkward for some Republicans: Roughly two-thirds of new clean energy infrastructure and manufacturing projects are in districts whose representatives voted against the law.

That said, the bill’s political utility depends on people understanding how it benefits their families and communities; at this point, polling suggests that fewer than half of registered voters have the faintest idea what it is, prompting advocacy groups like the League of Conservation Voters and Climate Power Action to run ads in key battlegrounds to get the word out. “It’s incumbent upon us to make sure that people across the country realize Democrats came together and did something that can save you money, that can create good-paying jobs, and that it’s gonna be good for the planet,” Tiernan Sittenfeld, the League of Conservation Voters’ senior vice president for government affairs, told me.

“Effort needs to go towards winning the win,” agreed Mary Small, national advocacy director of Indivisible. It’s always tempting to press ahead to the next battle, she added, “but in doing that, we leave a lot of impact on the table, in policies that never get implemented, or that get implemented in shoddy or incomplete ways.” Indeed, concerns are already being raised about a possible repeat of the disastrous rollout of the Affordable Care Act.

On the plus side, Small said, if properly marketed, the IRA and other manifestations of Bidenomics could become a powerful antidote to the anti-government narrative conservatives have deployed for decades. “We have a really empowered right wing that is very effective at convincing huge swaths of the American public that the government does not deliver for them, that it delivers for some other group of people,” she said. “Breaking through that and inoculating people against racialized divide-and-conquer politics is how you win the next piece of legislation.”

Among the 75,000 or so people who showed up at the March to End Fossil Fuels in New York in September, I encountered quite a few who knew the IRA was mostly a climate bill. They didn’t seem impressed. In fact, the primary goal of the event was ratcheting up the pressure on Biden, who would be in New York to address the U.N. The largest climate march since the pandemic, it represented a reset for the movement. But behind the scenes, schemers and dreamers were at odds about messaging: The decision to chastise the administration was raising concerns. “Elections are about choices,” Tiernan Sittenfeld noted. “Our best shot at actually meeting our shared climate goals is helping the president get reelected.” Representative Mike Levin, a Democrat from California and a strong advocate of more aggressive climate action, agreed. “Will we have Democrats, who actually want to address the climate crisis with the seriousness it requires? Or will we have climate deniers like [Speaker] Mike Johnson in charge, much less the biggest climate denier of them all, Donald Trump, who is now the de facto nominee of the Republican Party?”

As a result of this dispute, march organizers “had a really hard time getting funding,” according to Margaret Klein Salamon, a clinical psychologist turned climate activist who now serves as executive director of the Climate Emergency Fund. “Some of the larger climate funders thought that it would hurt Biden, which I think is just ridiculous. Like not only will they not support disruption, they won’t support a frickin’ march.”

The activist wing has cause for disappointment. As a candidate, Biden’s climate rhetoric sometimes took on a flinty, Dirty Harry Callahan resolve. “No more subsidies for the fossil fuel industry,” he vowed during one debate. “No more drilling on federal lands. No more drilling, including offshore. No ability for the oil industry to continue to drill. Period. Ends.” Challenged by a climate activist on the campaign trail, he ditched his prepared remarks and approached the young woman. “Kiddo,” he said, “Look in my eyes. I guarantee you. I guarantee you we’re going to end fossil fuels.”

After the election, however, “reality hit,” as The New York Times put it. (That pesky reality.) Biden’s attempts to cancel certain oil leases ran into legal and congressional roadblocks. Willow got the green light. In order to extend the debt ceiling, Biden expedited completion of the Mountain Valley Pipeline and weakened the National Environmental Policy Act, thereby limiting the scope of environmental review for future projects. (As one Texas representative gloated at the time, “Fossil fuels win and the greenies lose.”) According to federal data highlighted by the Center for Biological Diversity, Biden has approved oil leases at a faster rate than his Republican predecessor. Officials insisted they had little choice, but advocates remain infuriated that the White House hasn’t fought harder, called in the lawyers, used the bully pulpit, something, anything, to avoid the “moral and economic madness,” as U.N. Secretary General António Guterres has put it, of new fossil fuel infrastructure. Meanwhile, despite Biden’s claim in an August interview that, “practically speaking,” he had already declared a national climate emergency—a move supported by 58 percent of the public—he hasn’t, practically or otherwise. (Ali Zaidi declined to comment for this story, but, following a two-month-long email exchange, the White House provided a statement touting the administration’s accomplishments. The president, the statement asserted, “will continue to deliver on his Administration’s historic climate agenda.”)

Schemers rationalize the administration’s turnaround on political grounds: A massive spike in gasoline prices and the war in Ukraine, along with Republicans fulminating about a “war on energy,” made the optics impossible. Unfortunately for consumers, none of Biden’s concessions to the oil industry will affect the price of gas for years, if ever. They will, however, guarantee that millions of metric tons of carbon will be pumped into the atmosphere. Both natural gas and domestic crude oil production recently hit all-time highs, and despite talk of “energy independence,” much of that output will be exported. As usual, profits will flow to oil companies, while costs, financial and otherwise, will be borne by everyone else.

Michael Greenberg is pretty nerdy for a radical—lanky and awkward, with a fluffy head of hair and gentle demeanor that is hard to square with the spicy bravado of the Twitter feed he oversees on Climate Defiance’s behalf. (As the group wrote in October, “We are explicitly committed to ending the careers and decimating the reputations of those who disagree with us.”)

Greenberg grew up in Rockville, Maryland. He attended a Jewish parochial school, where he served as president of the Environmental Club. In 2014, while studying economics at Columbia, he organized his first major action, rallying hundreds of fellow students to risk arrest at the White House fence in protest of the Keystone XL Oil Pipeline. National news outlets covered the demonstration. “I think that really helped show me that, you know, disruptive, direct action is really the fastest and most effective way to catalyze change,” he told me. Eventually, under pressure from a host of environmental groups, President Barack Obama canceled the project.

Several years later, Greenberg helped organize a protest at the Line 3 pipeline that drew at least 1,000 people, Bill McKibben and Jane Fonda among them. And last year, after Senator Joe Manchin’s opposition doomed the Build Back Better bill, Greenberg and a dozen fellow activists blocked the entrance to the West Virginia coal plant to which Manchin owes his enormous wealth. Members of Sunrise later demonstrated at his $700,000 houseboat.

Greenberg launched Climate Defiance in April 2023 with a grant from the Climate Emergency Fund, backers of which include filmmaker Adam McKay, Aileen Getty (of the Getty oil fortune), Abigail Disney, and Succession’s Jeremy Strong. According to Klein Salamon, the CEF made the decision to put all of its money into “disruptive action,” as such protests are known, following an internal analysis last year that examined the impact of the variety of endeavors the group had bankrolled. “The disruptive grants that we made just vastly outperformed,” she explained.

Greenberg and his small crew have made the climate crisis personal in a way that few other groups have, aiming their fury less commonly at institutions or companies than at individuals in power. The resulting videos—tense, cringey, occasionally climaxing in a violent confrontation—are almost impossible to scroll past. Perhaps the clips’ most exhilarating feature is the rowdy invasion of exclusive spaces (fundraisers, conferences, policy forums) to which the rabble rarely gain admittance.

The group began with a few small actions targeting Zaidi and White House senior adviser for clean energy John Podesta, before cooking up a protest that seemed guaranteed to grab the media’s attention: blockading the White House Correspondents’ Dinner. “We had virtually no list, no social media following, no money,” Greenberg explained at a September fundraiser. “Everybody said, ‘You’re crazy. You don’t know what you’re doing. You don’t know how Washington works.’” Hundreds showed up. Tennessee Representatives Justin Jones and Justin Pearson offered their endorsements on the way inside. Since then, several other elected officials, including Representatives Ro Khanna, Rashida Tlaib, and Jamaal Bowman, have expressed support for the group and even appeared at its fundraisers.

Meanwhile, senior administration officials, political leaders, and corporate executives, including Chuck Schumer, Amy Klobuchar, Maura Healey, Jennifer Granholm, Tommy Beaudreau, Jaime Harrison, Pete Buttigieg, Kamala Harris, Rahm Emanuel, and Jerome Powell, have all felt the group’s wrath, as have attendees of the Jackson Hole Economic Policy Symposium and the Congressional Softball Game. “They’re doing actions on a very high tempo,” Klein Salamon noted.

It’s not hard to detect a theme: The organization’s quarry consists almost entirely of Democrats, never mind that a Republican administration would obviously be worse. In April, the Heritage Foundation’s 2025 Project released its “Mandate for Leadership,” a hardcover master plan for crippling the administrative state. Among other things, the blueprint calls for gutting the EPA, eliminating its climate-focused enforcement efforts, and dismantling offices within the Department of Energy aimed at mitigating the crisis. “If Donald Trump’s in the White House, then all of the other efforts will be historical footnotes, because his right-wing MAGA Republican minions will then work to strip all the environmental protections off the books,” Senator Edward Markey, co-sponsor of the Green New Deal, told me. “So the planet is on the ballot in 2024.”

“I mean, it’s complicated,” Greenberg acknowledged. “But Democrats are the ones holding the White House and the Senate at the moment, and the ones who are more movable. The whole question of ‘What do you do with the Republican death cult?’ I don’t necessarily know what the answer is.”

Haranguing one’s ostensible allies can be tricky. Climate Defiance’s decision to protest the annual gala of the League of Conservation Voters was a particularly tough call. That demonstration, Greenberg admitted during one speech to potential backers, “was at the very, very far edge of our comfort zone. But we decided that if we don’t take risks, who will?… And you know where we found ourselves the next day? In The New York Times.” Another awkward moment involved a Climate Defiance demo outside of a Biden fundraiser in Manhattan. Klein Salamon gave a speech on the megaphone, realizing only afterward that the fundraiser had been hosted by former Blackstone executive Tony James, “who I’ve been trying to get a meeting with for like six months,” she said. The meeting never happened.

The disruption of a fundraiser for Massachusetts Governor Maura Healey left a lot of climate activists “scratching their heads,” one movement stalwart told me. “They’ve jumped the shark on occasion.”

The choice to pressure Democrats “comes from a sincere, passionate place of being terrified about the climate crisis,” Sittenfeld acknowledged. “But if you look at what we’re up against, in terms of the incredibly well-funded fossil fuel industry that has spent endless amounts of money to defend their ability to continue to pollute as much as they possibly can, and the MAGA Republicans in Congress who do their bidding at every step, we think we should focus more on them.”

Even the protest at Manchin’s West Virginia coal plant has its liberal critics. While Klein Salamon believes the negative attention “was a significant part of why Manchin randomly decided to switch his vote,” the connection is speculative. (The protest was in April, and Build Back Better didn’t truly die until mid-July, only to emerge a few weeks later as the much-smaller IRA.) “The thought crossed my mind more than once that Joe Manchin needed to hear from activists,” Representative Levin allowed, but as to whether the protest influenced Manchin’s thinking, he suspects not. An environmental lobbyist who was involved in IRA negotiations insisted the action made the senator look more sympathetic, especially to his red state constituents. Ill-considered protests, the lobbyist argued, can quickly chill negotiations. “Usually, the more public and polarizing an issue gets, the more everyone has to start posturing, which makes it harder to make a deal in the room,” he explained, noting that what ultimately won the senator’s support was “massive amounts of oil and gas leasing.”

Such talk frustrates Michael Greenberg. “If you target the people on the right, people are like, ‘It plays into their hands!’ but if you target the people on the left, it’s, ‘Well, they’re doing all they can.’ Like, who do you target?”

As for Ali Zaidi, after Greenberg cornered the climate adviser in a basement room, the official surprised him by greeting him by name. Then, surrounded by catering equipment, schemer and dreamer engaged in a 10-minute heart-to-heart. Zaidi commended Climate Defiance on its ability to generate attention. He insisted he was doing the best he could, given the political headwinds. And he shared a little of his biography: emigrating from Pakistan at age 5, settling in Pennsylvania, taking on student loans to become a lawyer and make a difference in the world.

When Greenberg eventually emerged onto West Fourth Street, where his comrades were waiting, he seemed exhilarated but also oddly pensive. “It got really, really sincere,” he said, incredulously. “Like, it really felt like we had a connection.”

Asked if he thought the action had been a mistake, he said no. “But there’s complexity,” he added, “targeting people who are partially aligned…. It might serve us well to not be just the group that bashes Biden.”

At one point during their discussion, Zaidi had made a pledge. “He was like, ‘No matter how much you humiliate me and denigrate me, I’ll still be here fighting for you,’” Greenberg said.

Not everyone in the group seemed impressed by the sentiment. “Maybe that should be taken as a green light!” one member replied.

It’s no wonder schemers and dreamers find themselves at odds. Those who have fought for a seat at the table are naturally disinclined to make space for a crew of noisy upstarts. Never mind that the famous smoke-filled rooms where such deals are hashed out, once hazy with Cohiba fumes, now reek of Canadian wildfires; having mastered the inside game, schemers have a stake in its preservation, and this unspoken fidelity to the existing system tends to throttle their ambitions. The historical record suggests it takes dreamers—firebrands, visionaries, assholes—to expand the horizons of the possible. “Civil resistance is what’s required when you are confronted with entrenched power,” insisted Roger Hallam, the former organic farmer who co-founded Extinction Rebellion. “That’s just a sociological iron law.”

You win “great egalitarian reforms not through the inside game, not because a politician drove it, but because a social movement polarized the issue and then politicians followed,” agreed Paul Engler, co-founder of Momentum, an organizer training program, and co-author, with his brother, Mark, of the influential 2016 book This Is an Uprising. Barack Obama intentionally avoided talk of climate change as president, Engler pointed out. Now Democrats “realize it’s actually a popular issue to run on. That happened because of social movement pressure, not because of Nancy Pelosi’s political acumen.”

Indeed, one need only recall the heady days of 2018, when the Sunrise Movement burst onto the scene with a sit-in at Pelosi’s House office (attended by freshman Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez), a galvanizing action that forced what was until then an ill-defined and fanciful notion, the Green New Deal, onto the Democrats’ agenda. Pelosi was, as Sittenfeld puts it, “the most pro-environment, pro-climate action, pro-democracy speaker in our nation’s history ever, and by far.” Insiders said the protest “pissed her off,” perhaps justifiably so. But without that infusion of dreamer energy, annoying though it may have been, would Manchin’s and Schumer’s staff schemers have cooked up an IRA at all? Senator Markey recalled how an earlier attempt to tackle the crisis, the Waxman-Markey bill, “died in the Senate because there was no outside pressure. So that was the goal of the Green New Deal—to create a movement, especially of 18- to 34-year-olds,” he said. “That movement created the momentum that led to the IRA.”

The Sunrise story is also something of a cautionary tale, however. With breathtaking speed, the group sprouted more than 500 local “hubs” and attracted millions in donations. Meanwhile, it also morphed into a conventional nonprofit, with a top-down structure and establishment access, an evolution that wound up sapping the organization’s grassroots energy and splintering its membership. Then came Covid and a series of internal struggles, including tensions around race, that left the group adrift.

Greenberg is determined to avoid a similar fate. Within hours of the NYU disruption, he glanced at his phone in astonishment. A member of Zaidi’s staff had emailed, eager to keep the lines of communication open. “I can see how groups go down that inside-game rabbit hole, how you want to maintain that relationship,” Greenberg said later. He reasoned that Climate Defiance should “never prioritize relationships over the actions that need to be taken,” adding, “I think there’s something to be said for us being the sort of pure, attention-grabbing radicals that create space for groups with the more established relationships to come in.”

Radical action for its own sake will only take you so far, however. Climate Defiance has embarrassed some people who deserved it (along with a few who maybe didn’t) and put hundreds more on notice. It’s brought media attention to a crisis that remains maddeningly under-covered, considering the stakes. And it seems to have claimed a few bloody pelts. Harvard law professor Jody Freeman resigned from the board of ConocoPhillips as her tormentors had demanded, and Department of the Interior Deputy Secretary Tommy Beaudreau cashed it in just a few weeks after the group hounded him for signing off on Willow. Watching the group up close, I found its bravado inspiring. But a question lingered: Were these actions effective in the ways that really mattered?

Alec Connon, co-director of the Stop the Money Pipeline coalition, who led a September blockade of Citibank’s New York City headquarters to protest the company’s fossil fuel investments, believes three factors are necessary for an impactful action. It should be “highly targeted at elites, genuinely disruptive, and sustained over the long term,” he told me. Like most of Climate Defiance’s actions, the Citibank effort nailed the first two but not the third. Blame the lack of reinforcements. The American climate movement is “in a lull,” Paul Engler noted. “We don’t have a big organization with a big base that’s willing to put their bodies on the line.”

That may change. Such aggressive demonstrations are growing in popularity. According to a recent Yale study, nearly a third of registered voters support nonviolent civil disobedience on behalf of the climate, and 15 percent would consider joining such an action. According to the “3.5 percent rule”—the minimum slice of a population likely to force change on a government, according to research by Harvard political science professor Erica Chenoweth—that kind of participation would more than suffice.

To see what a vigorous climate movement can accomplish, consider the Netherlands. Just days before the Citibank protest, an estimated 10,000 demonstrators led by the local offshoot of Extinction Rebellion blocked a highway in the Hague to protest fossil fuel subsidies. Police dispersed them with water cannons and arrested 2,400. Protests resumed the following day and continued for a month. “It’s like, OK, you want to force the regime to do something, you go to the city, and you do not leave,” explained Roger Hallam, who contributed strategic advice to the organizers. Eventually, the lower house of Parliament called for a plan to end the subsidies. The challenge, Hallam said, is hanging in there. Nonviolent methodology “looks like shit until it wins,” he said. “The government goes, ‘No way, over our dead body.’ And then on day 28, they suddenly go, ‘Oh yeah, right then.’”

I reached out to Hallam amid a drumbeat of devastating climate reports and chaotic weather events, news so bad that I’d begun to wonder if any of the dedicated advocates I’d interviewed—from elected officials and policy wonks to radical cadre—had landed on the right approach. In a world of schemers and dreamers, Hallam is a screamer, sounding the alarm with bracing intensity. With his gray goatee, untidy ponytail, and beakish profile, he resembles a biblical prophet, and he often speaks like one: “The liberal, white middle class is desperately trying to pretend that we don’t actually face a crisis which will destroy the carbon state in the next 20 years,” he told me. “We all know what’s going to come afterwards, which is fascism. So, you know, wake-up time, isn’t it?” A sociologist who studied social movements as a Ph.D. candidate at King’s College, Hallam has also spent some 40 years at the barricades. He orchestrated Extinction Rebellion’s aggressive strategy, which forced the U.K. Parliament, in 2019, to declare a climate emergency, making Britain the first nation to do so. After being pushed out of the group (blame his allergy to compromise, appetite for arrest, and tendency to compare the climate catastrophe to the Holocaust), he co-founded Just Stop Oil, best known for snarling traffic in central London with its “slow march” protests.

Hallam believes one of the biggest issues facing the U.S. climate movement is numbers, and he highlighted the need for “systematic mobilization”: an ongoing organizing effort, akin to the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee’s Freedom Summer project, to educate people and welcome them into the fold. “You go out and do 1,000 public meetings,” he said, “which we did in the U.K. and Germany.” Each meeting brought in two to four new members willing to participate in civil disobedience, he estimates. Perhaps just as important, it created a mass constituency that understood the issue and was broadly aligned with the group’s tactics.

Asked whether, or how much, Americans should pressure a Democratic administration, Hallam, who has led protests against Greenpeace, Friends of the Earth, and other groups he considered insufficiently fervent, replied, “It’s a no-brainer. You have to push Biden as hard as you can.” But what about the election? What about the danger of, as Representative Levin puts it, letting the perfect “be the enemy of the very good”? In Hallam’s view, government officials, whatever their party affiliation, will make radical change only if forced to. “What Americans have to understand, those that want to maintain some sliver of civilization, is they have to create a civil resistance movement, not only in order to get carbon reductions in place, but also to revitalize democracy from the bottom up,” he said. “That’s the level of crisis your country is in. And obviously, everywhere else.”

After the September week of actions drew to a close, the Climate Defiance crew congregated at a gracious limestone in Harlem for a fundraiser. Plastic foam trays of Ethiopian food were laid out in the dining room along with snacks and a selection of beer and wine. Activists recognizable from the group’s videos mingled in the crowd. There was Krisha, who’d presented Jody Freeman with “Big Oil’s Bestie Award”; Betty, who’d tangled with Maryland Representative Steny Hoyer; and NASA scientist Peter Kalmus, who’d upbraided Interior Deputy Secretary Tommy Beaudreau. Joanna Smith, a member of Declare Emergency, who’d smeared finger paint on a vitrine at the National Gallery, was huddled with Steven Donziger, the crusading attorney who’s been fighting a bare-knuckle legal battle against Chevron for more than a decade.

Eventually we squeezed into the living room for a series of speeches. Adam McKay, beaming in via video chat, admitted that he was finding it hard lately to maintain the humor he’d mastered as head writer at Saturday Night Live “in the face of what we’re confronting,” namely the “beautiful, lush, green, teeming oceans, creatures … our families, our homes—all of it being destroyed by these big oil companies and the governments and the media they’ve controlled.”

Kalmus passionately described Climate Defiance and other youth-led groups as “nature defending itself.”

And the Reverend Liz Theoharis, a professor at Union Theological Seminary and co-chair of the Poor Peoples’ Campaign, invoked a line of Dr. Martin Luther King’s in explaining the necessity of lawbreaking: “There is nothing wrong with a traffic law which says you have to stop for a red light,” the civil rights leader had explained. “But when a fire is raging, the fire truck goes right through that red light, and normal traffic had better get out of its way.” A fire is raging right now, Theoharis said, and the nonviolent protest practiced by groups like Climate Defiance is “how you run through those red lights of greenwashing, and the corporate capture of media, and ‘Just wait a little bit longer.’”

They were right, I thought, absolutely. But at the same time, I couldn’t shake the nagging suspicion that these drive-by disruptions might not really be accomplishing what we all desperately hoped they were. The theater of political confrontation is a venerable tradition, of course. Climate Defiance’s viral clips, like all morality plays, are reconceiving the rules of decency, the meaning of virtue, the wages of iniquity for a new historical moment. They’re arousing the slumbering masses and delivering vital admonitions. And they’re offering a taste of empowerment to those of us who see a world disappearing and feel helpless to stop it. That alone is a perfectly worthy endeavor for a fledgling organization with just a handful of full-time members.

But then what?

Whatever you think of Roger Hallam’s fire-and-brimstone style, his remedy—essentially the same one advocated by Mark and Paul Engler and other experts on revolutionary change—seems right: We need a mass movement—teach-ins and training sessions, Slacks and snacks, street teams and superglue. We need to take on the sometimes joyful, mostly grueling work of organizing our neighbors; hashing out concrete, achievable demands; and turning out again and again, studiously peaceful but implacable until … well, until we notch a win and move on to the next goal. We need a new politics, one that combines the know-how of the schemers with the aspiration of the dreamers but draws its force from the collective power of the rest of us. That may sound daunting—particularly for those of us who, like me, grew up spoiled by economic prosperity and political calm. All the more reason to get busy.

On our way out of the stately Victorian residence, some guests took note of a brass plaque left behind by the building’s former occupant, the U.N. Mission of Vanuatu, a nation in the South Pacific that is experiencing the worst effects of the climate crisis well before most. A mere coincidence—but as folks said their goodbyes and filtered out into the night, I couldn’t shake the thought of that distant island, battered by devastating cyclones; surrounded by warming, rapidly acidifying waters; and slowly being swallowed by the sea. Maybe there was still time, I thought, not much, but some.