When The Bright Stream premiered at the Bolshoi in 1935, the ballet—which is set on a collective farm and features such characters as a man in a dog suit and a parade of vegetables—was denounced in Pravda as frivolous and ironic. Its composer, Dmitri Shostakovich, lost much of his work, and its librettist, Adrian Piotrovsky, was shot.

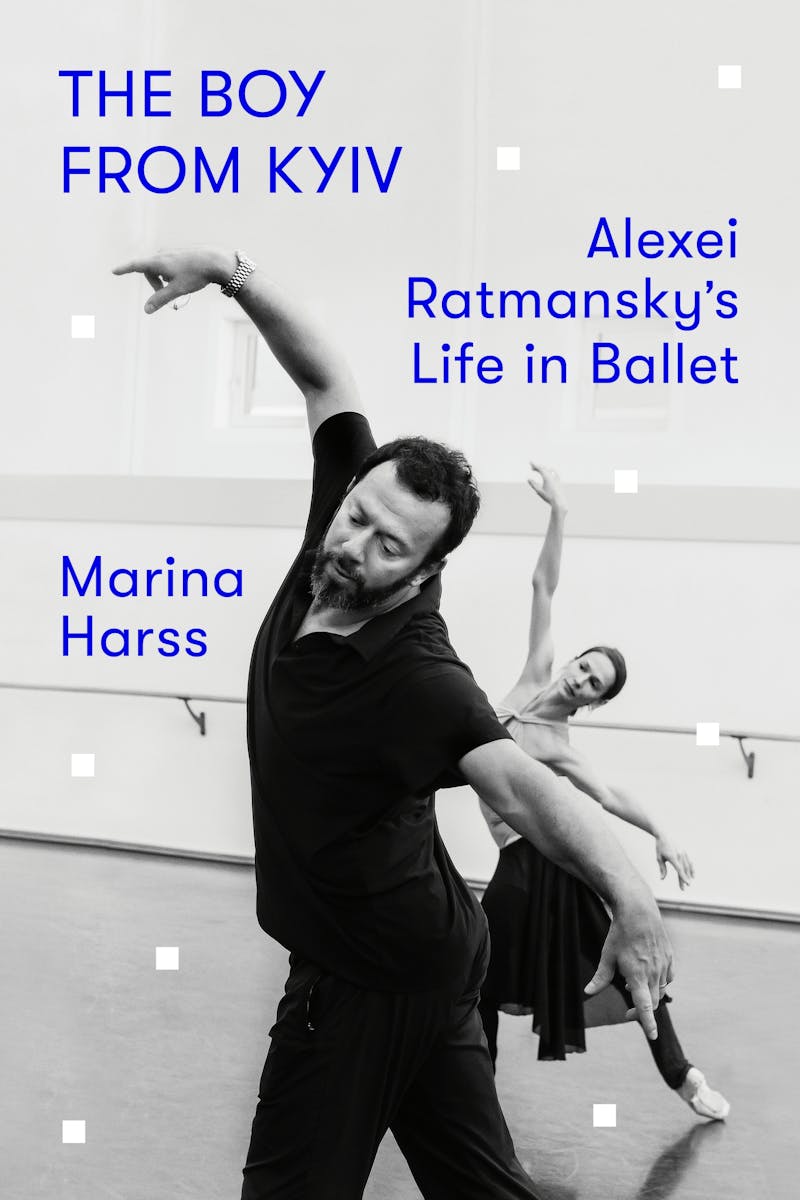

When the young choreographer Alexei Ratmansky brought his revival of The Bright Stream to New York in 2005, it made him the talk of the town. A program note explained that the piece was “not overtly political” and encouraged viewers to treat it as a comedy. In a time of relative stability, most critics did—praising the production as “dazzling” and witty. One enthralled audience member was the dance writer Marina Harss. “I left the theater elated and full of questions,” she recalls in her new book, The Boy From Kyiv: Alexei Ratmansky’s Life in Ballet. Who was Ratmansky—and how had he managed to take something that could have been “anachronistic, ridiculous, stylistically retrograde” and make it human—even funny?

Ratmansky has been hailed as one of a handful of choreographers reinvigorating ballet for the twenty-first century, rescuing the art form from its decades-long slump. In the epilogue to her 2010 book, Apollo’s Angels, historian Jennifer Homans famously argued that ballet was dying—that no one had stepped in to the fill the void left by the twentieth-century greats (George Balanchine, Jerome Robbins, Antony Tudor, Frederick Ashton). “Contemporary choreography veers aimlessly from unimaginative imitation to strident innovation—usually in the form of gymnastic or melodramatic excess,” she wrote. Whereas ballet was once a vibrant part of American culture, a site of Cold War competition alongside the Olympics and outer space, it had become increasingly marginal, with companies relying on the Nutcracker to survive.

Reversing this tide would be a tall order for any choreographer, no matter how brilliant. Susan Jaffe, artistic director of American Ballet Theatre, recently told The New York Times that Ratmansky has “propelled ballet to heights far beyond what we thought was possible 20 years ago.” In fact, ballet is more niche today than it was 20 years ago. Between 1982 and 2010, ballet attendance among college-educated adults fell by nearly 50 percent. Meanwhile, dance coverage has been dropping out of mainstream publications: In the 1970s, a new ballet might be reviewed by 10 different critics; by 2015, there were only two full-time dance critics left in the United States. Last year, one of them was laid off. Add to this that Ratmansky himself is deeply concerned with ballet’s past, whether unearthing its history and traditions or resurrecting forgotten works like The Bright Stream. At a time when audiences are dwindling, and dancers are known more for their TikToks than their technique, it may be unwise to anoint as the art form’s future a choreographer so thoroughly steeped in ballet history.

Harss tries to present instead a more immediately accessible version of Ratmansky, tracing what she sees as his political awakening. The title, “the boy from Kyiv,” refers to a nickname he was given at the Bolshoi Ballet School as well as his commitment to his home country in the wake of Putin’s invasion of Ukraine. Harss attempts to cast her subject, who has spent his life ensconced in the insular world of ballet, as a newly political artist. But she also manages to highlight, paradoxically, how detached Ratmansky has often been, placid toward those around him and largely oblivious to sociopolitical turmoil—a man more concerned with ballet itself than with the world at large.

Born in 1968, Ratmansky was raised in Kyiv by his mother, Valentyna, a psychiatrist, and his father, Osip, an engineer from a secular Jewish background. Alexei moved to Moscow to study at the Bolshoi Ballet School when he was 10, and, upon graduating, joined the Ukrainian National Ballet back in Kyiv. As a dancer, he developed a reputation for musicality, elegance, and a pure technique, and did stints with the national companies of Canada and Denmark. “He was inside the music,” one director said. “It’s so clean, it’s almost as if someone had washed each step,” said another. He began entering choreography competitions while dancing with the Royal Winnipeg Ballet, and in his early thirties stepped back from dancing to focus on choreography. Ratmansky landed in New York in 2009 as the in-house choreographer at American Ballet Theatre, and in August he moved across Lincoln Center Plaza to become artist in residence at New York City Ballet.

Ratmansky’s body of work, which spans around 100 ballets, draws on the many styles he assimilated as a dancer, from Russian bravura and folk dancing to Danish naturalism and American speed. He is as comfortable reworking a classic narrative ballet (he has made his own versions of Cinderella, Swan Lake, and Sleeping Beauty) and resuscitating old music (often by Shostakovich) as he is following his own instincts and commissioning contemporary composers. Humor, and even goofiness, are a hallmark of his work. The 2003 Bolshoi premiere of The Bright Stream marked the first time in 50 years that “the Moscow public laughed out loud at a classical ballet,” one Russian critic observed. His 2010 Namouna, a Grand Divertissement features a bevy of women inexplicably wearing swimming caps, as well as a solo for a cigarette-smoking femme fatale. His surreal, evening-length Whipped Cream (2017), which loosely follows the dreams of a boy who’s fallen into a food coma, is partly inspired by his wife’s fondness for cans of whipped cream.

His output has been prolific: At 55, Ratmansky has worked with pretty much every major company in the world. His boss at ABT, Kevin McKenzie, calls him a “creation junkie”; Harss portrays a man obsessed. “When he wasn’t in the studio working on one project,” she writes, “he was at home thinking about the next, and the one after.” His career has been marked by a willingness to buck trends—presenting story ballets when abstract work was in fashion; dipping into the Bolshoi’s archive of 1930s ballets, which risked being seen as Soviet kitsch; coaching elite dancers, who prided themselves on their athletic jumps and turns, in a subdued style of nineteenth-century ballet.

Ratmansky emerges, in Harss’s telling, as mild-mannered and easygoing—the product of loving and attentive parents, and an easy magnet for friends. When he moved from Kyiv to Canada at 24, his director recalled that “he fit in immediately.” As a dancer, his difficulty summoning strong emotion sometimes held him back. Working with the choreographer Mats Ek in 1999, Ratmansky—then a soloist with the Royal Danish Ballet—struggled to convey his character’s intensity. “He wanted me to look angry, but it was hard, because I almost never get angry,” he tells Harss.

As a choreographer, his manner in the studio is unfailingly polite, no matter how stressful the circumstances. In 2001, he had been commissioned to simultaneously create a new Nutcracker and a new Cinderella—in different countries. Even so, one Danish dancer recalled, “In the middle of the most intense snowflake rehearsal, if somebody sneezed Alexei would stop and say, ‘God bless you.’” Perhaps the tensest rehearsal described in the entire book involves a minor disagreement over the height of an attitude derrière. Ratmansky repeats himself a few times, and finally—in what seems to be his version of exasperation—says, “How can I get you to have the attitude down here?” In this, Harss—an expert in Ratmansky’s moods—sees a “very polite war.”

Maintaining this level of decorum is remarkable when you consider the conditions under which choreographers work: “against the clock and under the eye of maybe twenty people who stand there and stare at you when you get stuck,” as Joan Acocella put it in her 2001 review of Greg Lawrence’s Dance With Demons: The Life of Jerome Robbins. Robbins, who choreographed ballets like The Cage as well as Broadway hits Fiddler on the Roof and West Side Story, “screamed at dancers, insulted their work, insulted their bodies,” writes Acocella. Stephen Sondheim labeled him a sadist. But Robbins’s bullying wasn’t so far out of the ordinary. “Nijinsky made people cry; Martha Graham slapped her dancers,” Acocella reports. More recently, Peter Martins—who served as artistic director of New York City Ballet from 1990 until 2017—regularly lost his temper in rehearsals; one former child dancer accused him of grabbing him by the neck and digging in his nails.

In the swell of #MeToo, dancers began to reckon with the behavior of some of their idols. In early 2018, Peter Martins was accused of sexual harassment and physical and verbal abuse; later that year, NYCB was sued by a former student alleging that her boyfriend, a principal dancer almost a decade her senior, had secretly filmed her during sex. In 2021, the celebrated British choreographer Liam Scarlett died by suicide amid allegations of sexual misconduct. By contrast, the most salacious moment in all 496 pages of The Boy From Kyiv comes when Ratmansky sends Wendy Whelan—a New York City Ballet star who was nearing retirement, but for whom Ratmansky wished to create one last piece—a text punctuated with heart emoji.

Despite a relentless schedule of work and travel, Ratmansky has maintained a remarkably stable personal life. He has been with his wife, the Ukrainian dancer Tatiana Kilivniuk, since his early twenties, and they have a son, 25-year-old Vasily. If the current discourse—exemplified by books like Claire Dederer’s bestselling Monsters: A Fan’s Dilemma—often questions whether it’s even possible to be an artist without abusing anyone, then Harss’s book suggests an encouraging answer.

Yet there is a side of Ratmansky that is slightly out of step with the world around him. Harss glosses over a few of Ratmansky’s gaffes—spending only a page on an inflammatory Facebook post that garnered more attention than most of his ballets. In 2017, Ratmansky posted a photo-shopped image of a ballerina hoisting a man over her head, alongside the caption: “Sorry, there is no such thing as equality in ballet.” Men lift them and escort them offstage, he explained. Women dance on pointe and receive flowers, “and I am very comfortable with that.” Harss admits that the comment was “tone-deaf,” but excuses it—without much explanation—as “tongue-in-cheek.” Ratmansky dealt with the backlash mostly by ignoring it; Harss takes a similar approach, swiftly returning her focus to his work.

But Ratmansky’s comment wasn’t entirely isolated. Harss neglects to mention an interview he gave to The New York Times earlier in 2017, in which he was asked for his thoughts on the gender gap in choreography. That year, according to the Dance Data Project, over 80 percent of ballets performed at America’s largest companies were by men. “I don’t see it as a problem,” Ratmansky said, before name-checking a few successful women. Whatever Ratmansky’s true feelings about gender politics, there is something guileless about his public statements. In 2006—two years into his reign as director of the Bolshoi—he told an interviewer that he “would actually be happy to fire” a third of the dancers who worked for him.

Perhaps this naïveté stems from his lifelong immersion in the cloistered world of ballet. Dancers’ obliviousness to the world around them—from the collapse of communism to the Chernobyl disaster to the spread of Covid-19—is a theme of The Boy From Kyiv. Ratmansky’s time at the Bolshoi Academy coincided with the last gasps of the Soviet Union, but he and his classmates were so absorbed in their training that they barely noticed. Their days were carefully prescribed—from their 8 a.m. wake-up call to their 9:30 a.m. ballet class and their morning academics to their lunch (of compote and potatoes) and their afternoon acting lessons and pas de deux. “Outside of the school, Russia was a poor and chaotic country,” one of Ratmansky’s classmates tells Harss, “but inside, where we were, it was full of creativity.”

Company life was equally all-consuming. In 1986, Kilivniuk was dancing with the Kyiv Ballet when a reactor at the nearby Chernobyl nuclear power plant exploded, blanketing the area in toxic gas and sending radioactive clouds as far away as Sweden. Kilivniuk only learned about the disaster from a friend. “I was like, okay, what is Chernobyl?” she recalls asking. “What is a nuclear power plant? What is an atom?” She and her colleagues were forced to keep performing, even as audiences dwindled; by the time she was allowed to go home, her clothes were radioactive and she was developing anemia.

In March 2020, Ratmansky was busy preparing to open Of Love and Rage in Costa Mesa, California; he paid little attention to news reports that a deadly virus was circulating. Two years later, he was working at the Bolshoi when he heard rumors that an invasion was imminent. “I thought I would try to ignore the news and be professional and continue working,” he said. Putin fired missiles into Ukraine the next day.

Even as a child, Ratmansky was sheltered from the harshness of Soviet life. His parents protected him from their painful history as well as from ordinary tragedies. They never told him about their experiences during World War II. When his great-aunt died just before his winter break, the family rushed to hold the funeral before he got home.

If women and beauty were Balanchine’s main subjects, and English mores were Ashton’s, then ballet, and ballet history, are Ratmansky’s. “There is such richness in the classical vocabulary that my whole life would not be enough to explore that alone,” he told The New York Times in 2017. When he had a rare month off in 2013, he used the time to pore over 100-year-old manuals of dance notation, trying to decipher the cryptic lines and dots that had once represented ballet steps and musical notes. (Until the advent of video cameras, choreography was handed down orally, from dancer to dancer.) Every night, he and Kilivniuk would try to decode them together. “We would separate, decipher the steps for ourselves, and then compare,” Kilivniuk tells Harss. Eventually, they managed to parse the original scripts for such classics as Sleeping Beauty, Swan Lake, and Paquita, which had been distorted by a century-long game of telephone. Ratmansky devoted much of his energy, over the next few years, to reviving them in the original style—“part archaeology, part séance,” as Harss put it. While Harss celebrates Ratmansky’s discoveries—a pas de deux in Swan Lake, for example, was once a pas de trois—it’s hard to imagine the average ticket-buyer getting excited about this.

The humor of Ratmansky’s work, too—the satires and spoofs—depends on the audience’s familiarity with the ballet canon. Jennifer Homans, who has not embraced Ratmansky with the same enthusiasm as Harss, wrote in The New Republic in 2011 that his work is “consistently cluttered with influences, in-jokes, and references to old ballets, to the point where his own voice gets lost.” The Bright Stream (which Homans—less willing to overlook its gory history—called “a striking lapse in taste and judgment”) features a male dancer performing a parody of the Romantic-era ballet La Sylphide. The joke is not just his costume (long tutu and pointe shoes) but the angle of his shoulders and the height of his arabesque. In Le Carnaval des Animaux (2003), the clumsy Elephant is danced by a ballerina who can’t straighten her legs; the Swan riffs on Anna Pavlova’s melodramatic 1925 solo The Dying Swan.

Ballet is not Ratmansky’s only influence. He has drawn inspiration from modern art, Jewish folklore, museums in Copenhagen and Greece. But in considering his typically lighthearted tone, his “aversion to drama,” and his endless fascination with ballet itself, it’s hard not to look to his seemingly untroubled youth and his idyllic memories of ballet school.

The Danish writer Tove Ditlevsen referred to childhood as “that library of the soul from which I will draw knowledge and experience for the rest of my life.” Of course, a traumatic childhood is not a precondition for making great art. But I can’t help thinking of Balanchine, abandoned at the Imperial Ballet School and nearly starving during the 1917 revolution. Or of the effeminate Frederick Ashton, bullied at his British boarding school and abused by his homophobic father. In her memoir Push Comes to Shove, Twyla Tharp recalls creating her first dance after watching her father chop off a rattlesnake’s head.

Before the war, Ratmansky dithered on his identity, sometimes saying he was Soviet, sometimes Russian, sometimes half-Jewish. In 2022, that changed. “I consider myself Ukrainian,” he tells Harss. Ratmansky is using his social media platforms to condemn Putin’s war and the Russian dancers and directors who support it. He asked the Bolshoi to stop performing his ballets (the request was ignored) and staged Giselle for a company of Ukrainian refugees. His new Wartime Elegy celebrates Ukrainian folk heroes, and he recently launched a Telegram channel dedicated to Ukrainian ballet history. But when Ratmansky was asked, in the fall of 2022, if the war had changed him as an artist, he demurred. “I’m definitely changed as a person,” he said. Asked what it meant to be a political artist, he said he didn’t know.

Do we need Ratmansky to justify himself? A central subject for him has always been the sanctity of art. Three years ago—before Covid, before the war—Ratmansky debuted his Voices at New York City Ballet. Hailed as an artistic breakthrough, Voices consists of six solos, each set to recorded speech by a female artist. In the finale—set to interviews with the painter Agnes Martin—10 dancers flit in and out of horizontal lines, like a Martin painting brought to vibrant, pulsating life. Martin’s enigmatic pronouncements have the ring of an exasperated manifesto. “Musicians compose music about music,” she says. “Painters can paint about painting, but my painting is about meaning.” She sounds weary. She sounds as if she’s rejecting every request for an artist statement, every expectation that an artist ought to explain her work. “I like the horizontal line better than every other line,” she says in the documentary from which these quotes were drawn. “You have to remember that I paint with my back to the world.” Something in her tone—or maybe in her tendency to veer between nonsense (“I gave up facts entirely”) and profundity—makes you want to leave her alone and let her paint.

I saw Voices earlier this year, and I thought it was one of the most powerful ballets I’d ever seen. Listening to Martin and watching the dancers, I felt, fleetingly, that I’d understood something. What, exactly, I can’t remember. But you don’t go to see a Ratmansky ballet for the message. You just go to watch.