Shirley Hazzard liked to tell people that the first short story she ever wrote was a tale of genius finally recognized. It’s set sometime in the late 1950s. On an Italian terrace just losing the heat of the day, old traveling companions gather for dinner. They sit as if in the “purposeful isolation of a ship at sea,” the lights of Siena rolling across the horizon. They have spent their weeks abroad enmeshed in blissful camaraderie. And then two newcomers arrive: a mother and her son.

The mother is a domineering figure who makes the entire table uneasy by immediately complaining about her son. Harold, she declares, missed the sights in Florence because he holed up to read and write! The young man is “silent” and “disheartened.” The evening seems to have “lost its balance.” When his mother goes to bed, he agrees to read his poems. The diners expect more embarrassment on his behalf. But they are mistaken: Harold’s poetry awes the crowd. He comes into himself as he reads; the maid leaves the table uncleared, wary of disturbing the rapt group. The other young men separate into “solitary, reflective attitudes that conceded this unlikely triumph.”

Hazzard’s own story was one of unexpected triumph. She was just shy of 30 years old and had never written for any publication when the work began to burst out of her. After an introduction from critic Dwight Macdonald (whom she met as a fellow guest at an Italian villa much like the one Harold visits), she submitted a few stories to the New Yorker fiction editor William Maxwell, who promptly accepted “Harold,” and within six months signed Hazzard to a first-read agreement. A year later Macmillan published her first collection. As Brigitta Olubas reports in her new biography, Shirley Hazzard: A Writing Life, Maxwell greeted Hazzard’s fiction as “the work of a finished literary artist about whom they knew nothing whatever.” If anyone did tutor Hazzard, even Olubas, in her almost 500 pages and with access to her diaries and letters, can’t figure out who it might be. It’s most likely the genius was always inside her, waiting for the right circumstances—for the right audience—to crack it open.

Hazzard had poured a great deal of her own experience into the 3,000-word story of Harold. The steamrolling mother. The splendor of Italian nights and intellectual conversation. The experience of surprising a worldly clan of intellectuals with her own erudition. The ecstasy and g-force thrill of achieving escape velocity from drab beginnings. Australia, especially the Australia of the 1930s and World War II, was the nothingness Hazzard lifted herself out of, in life and in fiction. She was a lifelong striver who wrote about lifelong strivers, and a devotee to the past—the prose, the literary elegance, the implications of the past—who dragged it into the present. The fictional lives she built were ways to understand and create her own.

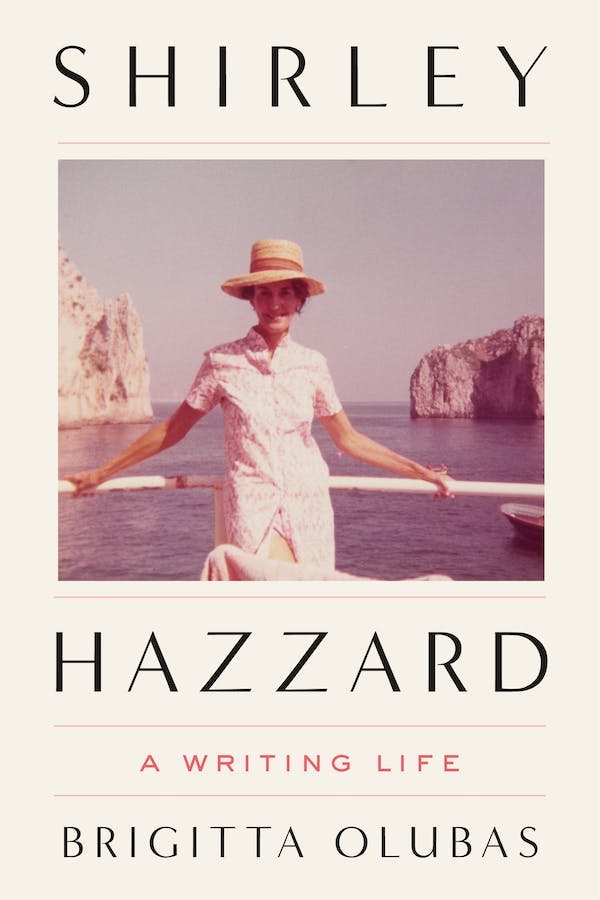

In the most enduring picture of Hazzard, taken in 1963 upon the publication of The Cliffs of Fall, pearls embrace her thin neck and a bouffant holds itself at attention. Her whiplike eyebrows arch, two silent judges on her face. For the rest of her life, publicity photos captured the same woman, virtually stuck in time: hairspray as armor, smart cardigan, a look of total control and elegance. Olubas calls her “a refined beauty”—refined being a word used exclusively to describe the wealthy. The poet Edward Hirsch called her “the most cultivated person” he had ever met, though he “knew even without her telling me that she did not come from a cultivated background,” a detail she never hid but did try to outrun.

Born in Sydney in 1931, Hazzard was perpetually dissatisfied with the world she grew up in. “History itself proceeded, gorgeous, spiritualized, without a downward glance at Australia,” she writes in her 1980 novel The Transit of Venus. She found suburban Sydney “provincialissimo,” she told The Paris Review in 2005, “especially to a reading child who had the evidence, on the page, of other worlds, other affinities.”

There was, in her telling, no world-class opera, ballet company, or pedigreed symphony to speak of. The fine arts scene of her childhood, she repeatedly insisted, was abysmal—the few quality works displayed in Sydney were “displayed in such gloom and institutional dreariness that one dreaded the Sunday afternoons on which one was taken there.” Did she know in adolescence that she was missing out, or did Sydney only look so drab in hindsight, from the vantage of a culturally bountiful adulthood? Either way, Hazzard clamored to head anywhere with writers and artists—to stand in places recognizable to her imagination because she’d spent so much time there in books.

And Hazzard didn’t merely read. Her repertoire of memorized poetry ranged from Samuel Johnson to Apollinaire to Elizabeth Barrett Browning. Throughout her life she’d declaim at parties, and she lent this talent to the characters in her novels, who use their prodigious poetic memories as a way to ingratiate themselves with other literati. Literature was the force that propelled her out into a wider world. She began to learn Italian at 18 because she wanted to read Leopardi in the original. In 1956, at 25, she took a job in Naples for several years; from there she first vacationed at Villa Solaia, the place that she claimed made her want to write and the setting for so much of her early fiction, like “Harold.”

Hazzard first broke away from Australia with her family, hopscotching their way around the world. Her father was a high-ranking (and the nation’s highest-paid) civil servant; as a result, when Shirley was 16, the family moved to Hong Kong, then back to Australia (“a dying, a death”). They went on to New Zealand—where her parents sent her, despite her brilliance, to Miss Hale’s secretarial school, which she called “the Blacking Factory”—then back to Australia again. Finally, on to New York City in the fall of 1951, where she noted that having arrived wasn’t enough. “We lived on Fifth Avenue and we had a comfortable life but it didn’t count in the hierarchy of New York. It was being rich that counted.”

Olubas’s biography feels the drag of these early years; it too is pinned down until Hazzard begins writing and meets Flaubert scholar and translator Francis Steegmuller, her husband of over 30 years and partner in cultivated living (it helped that Steegmuller’s formidable first wife, Beatrice, left him a considerable inheritance and a pile of valuable art to sell off when writing income grew thin). After that, Olubas explains, “Much of her attention … turned to obscuring, refashioning, and forgetting where she had come from.” Caro Bell, one of the orphaned sisters at the center of The Transit of Venus, sprang from that refashioning. Caro could escape Australia, marry rich, and—most importantly—fashion herself into a dynamic creature in touch with the movement of the world, because Shirley Hazzard could too.

Hazzard and Steegmuller spent spring and autumn most years in Italy, either at their apartment in Naples or on Capri; they returned to New York in summer and winter. Hazzard’s diaries were enclosed in Hermès leather, her walls hung with Renoir oils and Degas pastels; her dinner companions ranged from Nobel Prize–winning scientists like Harold Varmus to cultural historian Jacques Barzun, to fellow novelist Elizabeth Bowen. In New Zealand she’d haunted a bookshop, hoping to meet literary persons of interest (she didn’t); now the New Yorker crowd gleefully absorbed her—Olubas notes party after party with Anne Fremantle, Maxwell, Macdonald. In The Transit of Venus, Hazzard writes that “Australia required apologies,” but her intellect smoothed out her path. Friends characterized her as someone who “spoke in arias”—a person with whom conversation meant “finding a moment when you could interrupt.” After a dinner together, Alfred Kazin wrote of her: “the magic of Shirley the Hazzard. When will we learn from a woman like this—with her incredible gentleness, the light that fills where she is, that love is a form of intelligence.” Never snobby, Hazzard invited in strangers off the street and offered them books, talked intimately with Caprese shop owners. She was, perhaps, always nervously aware of the social distance she had traveled in such a short time.

Though critics have often compared her fiction to that of Henry James (syntactically complex and exacting about class), that description really only applies to her later novels. The stories assembled in her first collection, The Cliffs of Fall—some of, if not the, greatest stories of thwarted love produced in the last century—move in deep but narrow grooves. They’re kitchen table reckonings, in which affairs (Hazzard and her characters had predilections for older, married men) sputter out or come to a head while lovers put coffee cups on the draining board or moodily butter toast. In “A Place in the Country”—Hazzard’s very best—a young woman named Nettie conducts a naïve summer dalliance with her cousin May’s husband, Clem; after May finds them out, Clem abandons a distraught Nettie, but not before he “ministers” to her one last time, unfastening the belt on her dress as the story closes. A simple plot, complicated by the characters’ self-sabotaging indirectness; Hazzard’s characters so often avoid saying what they mean or even admitting their thoughts to themselves that they end up acting against their own interests and intentions.

When she started writing fiction, the sting hadn’t worn off a capsized engagement in her late teens that ended when her fiancé, Alec Vedeniapine, “an extraordinary man of action … of intellect,” took up in England as a farmer: He couldn’t even afford furniture, and friends saw the “deep comedy” of stately Hazzard potentially mucking out stalls. The inevitable breakup devastated Hazzard, but the parting eventually came to seem a blessed catalyst. In 1982, thirty years after they ended their relationship, she visited Alec and his wife on their farm and noted, “I ‘renounced’—failed life with him, and went on, miraculously, to life. He renounced his larger life.” As Olubas notes, “she measured her own achievements against Alec’s and found him, above all, wanting.” The “larger life” Alec gave up was the one she had—books and rigorous conversation and townhouse dinner parties.

Hazzard’s ambition as a writer grew in leaps between her four novels, which she published over the space of 37 years. Her first two, The Evening of the Holiday and The Bay of Noon, flutter over similar terrain as The Cliffs of Fall. The Evening of the Holiday is a story of slowly degrading love set against the ancient monuments of Italy. From its first sentence, Hazzard nods again and again toward the new nation’s endless history: Tancredi, an older Italian man, is tasked with showing Sophie, a young English visitor, a marble fountain from the twelfth century that sits unremarkably in a private garden. Sophie drops her gold bracelet in its water and fishes it out (a scene I imagine Ian McEwan was paying a debt to in Atonement), and Tancredi falls in love. As their relationship heads toward inevitable dissolution, Sophie continually finds herself entranced but hemmed in by the old world. On a walk across town to meet Tancredi, she runs into a swarm of villagers dressed in silk and velvet medieval costume, reenacting victory in a fifteenth-century battle. Sophie, terrified, ducks into the ancient cathedral and finds herself trapped there: The salvation of the past eludes her.

The Bay of Noon is ostensibly a love triangle, but

at its heart it’s a story about a young émigré who attaches herself to a woman

who possesses all the cultural cachet she lacks. Emigration has been a

revelation for her—as a child she was sent from London to Cape Town during the

Blitz, and the woman in charge of the transport misnamed her: “I went on board

as Penny and disembarked as Jenny,” she recalls. Her reinvention continues in

bombed-out Naples, where Jenny latches onto Gioconda, a member of the shabby

gentility and hostess to the city’s creative class. Jenny is no cynical social

climber—the connection is felt both ways; her devotion is genuine—but Hazzard

cleverly paints her aspirations in terms of her surroundings. Gioconda’s

first-floor apartment, in a palazzo once entirely inhabited by her family, is

adorned with “thick curtains, thin carpets, worn velvet chairs and footstools.… Plants and vases, pencils and matchboxes … arranged themselves there with a

look of purposeful incongruity, like objects for a still-life.” In her more modern box of an apartment on the

water, Jenny tries to replicate it with “a shelf of flowers painted on gesso … a

piece of fractured majolica.” Hazzard’s protagonists are creatures formed in

awe—of where they’ve ended up and who they might become.

World War II—the backdrop of Hazzard’s childhood—had both disrupted and cemented the permanence of history. She endlessly reflects on it in her fiction: Characters spill their war stories, common touchstones in a quickly changing world. Flung out in the distant Pacific, Hazzard had weirdly missed out on the war while also feeling its effects keenly. Years of dread (mostly of occupation by the Japanese) didn’t amount to much, but her school was evacuated to the countryside, and Italian prisoners of war were interred on adjacent land. (An infamous POW would turn up as a plot linchpin in The Transit of Venus.)

Hazzard would spend most of her writing career reconfiguring the war into an event that seeped out of the past and into the present. The formalities and propriety, the smart dresses and long plaits of dark hair, the drafty country estates and careful etiquette—these aren’t covers for a history Hazzard wanted to avoid but niceties to juxtapose with the ravages of war. For every daintily sipped coffee, there’s a jar of Marmite like the one a character in The Transit of Venus saves, desperately, as an act of hope, during his years as a Japanese prisoner of war. She offers grace, but only with horror.

By the 1970s, Hazzard was living what Olubas calls “a conjugal version of literary high life” with the celebrated Steegmuller, and she slowed her pace considerably—partly to write about the United Nations, partly to bolster her husband’s writing (and complain about it, repeatedly, in her diaries: “No one to take my part. Always”), and partly because she zoomed out to take what Matthew Specktor has called “a sometimes uncomfortably Olympian perspective.” The Transit of Venus, her masterwork, which she labored over for a decade, uses for its title that rare, much-studied phenomenon in astronomy, an event that spurred explorers and scientists to spend years at sea and abroad, waiting for the moment a celestial body altered their view of the heavens. The novel announces itself as grand and cosmic from its first line (“By nightfall the headlines would be reporting devastation”), when a young man arrives at the door of an English country home amid a once-in-a-lifetime rainstorm. The home belongs to the Thrale family, and the young man is Ted Tice, an astronomy student who works with Mr. Thrale. Ted’s abiding devotion to Caro Bell will form her life’s backbone—his grounded moral center will shape her view of the mad postwar world, even as she keeps him at a distance.

But Transit of Venus also concerns itself with the minuscule—that tiny dot of Venus moving across the vast sun—in the miscalculations and determination of one young woman from the far side of the world. Caro and her sister Grace are Australian, orphaned at a young age and now residing in the Thrales’ war-weary house, like Victorian wards, until Grace marries the family’s eldest son. Grace chooses placid stability in a life among the ruling class, but headstrong Caro, with an Isabelle Archer–like pick of three men, will choose upward mobility, at some cost. “I wanted to be as true as possible to a phenomenon now passing away from our society,” Hazzard explained, “the accidental meeting of man and woman and a sense of destined engagement that would possibly last out their lives. This, to serve as counterweight to the huge disillusion of a ravaged world.”

(Hazzard, a woman who once sent a would-be mugger running with a slap, also knew how to slip in humor. Venus contains a line I’ve long revered, about a needy and draining half-sister: “She was one of those persons who will squeeze into the same partition of a revolving door with you, on the pretext of causing less trouble.”)

Olubas dedicates a chapter to the novel, but oddly shares very little about the process of its composition. Instead she focuses on the huge implications of its success for Hazzard: how it immediately hit the bestseller lists, won her wide approval from critics and fellow novelists, and implanted in Hazzard a clear sense that she had now “made it.” After she received the National Book Critics Circle Award in 1980, she remarked that it indicated the acceptance of “someone born far from this country” into “the writing life of this land.” Even if, by that time, she had spent two decades among the highest echelons of literary America, clinking glasses with leading editors and appearing in their pages.

It took her 23 more years to publish another novel, The Great Fire. In between those two works, Steegmuller’s health deteriorated until he could no longer care for himself, and he died in 1994. If The Transit of Venus relocated its protagonist to the center of the world, The Great Fire relocates the center of the world to the crater left behind by American atomic bombs. But it bears the features of late style. It’s overwritten, its characters pushed to extremes that almost parody her earlier interests: The central story is the unlikely love between the 32-year-old war hero Aldred Leith, a former POW who is writing a book in postwar Asia, and teenage Helen, a girl given to reciting poetry like Hazzard herself. Hazzard elevates obliqueness to the detriment of clarity. The drafts and rewrites and labor of two decades plus are sometimes obvious on the page.

Adrift after Steegmuller’s death, Hazard spent much of her later years in “reverie,” as she put it, using her novel-writing as a chance to stew in the wreckage of her relationship with Alec Vedeniapine and her early adulthood spent “in that private tragedy, cruel destiny.” With its happyish ending (a change Hazzard made just before the book went to press), The Great Fire eventually turned into a bridge for her, a way to understand that perhaps she deserved the intimate joys and public successes of her life. It helped that the novel, even with mixed reviews, put her on stages and in front of clapping admirers, as she chatted at the 92nd Street Y with Richard Ford and took home the National Book Award. It also sent her back to Australia to receive the country’s most prestigious prize. She reveled.

Her final years brought catastrophe on all fronts. After several years in bed, intellectually unreachable, she died in 2016, a year that feels impossibly close to the present for a woman so bound up in the past. Once-abundant money had grown so tight that friends intervened to keep her in her Upper East Side apartment. Her cognition began to fail, an intellectual prison for a woman so invigorated by repartee and discussion. She slowly shrank from her big, broad world. Olubas is tender but unsparing: At a dinner for the American Academy of Arts and Letters, one of her last public outings, Hazzard “put her head down on the table among all the other guests and cried ‘Where am I?’” until a friend took her home.

She was in New York, a city she’d inhabited for over six

decades, but that sense of being adrift—of always working toward something

over the horizon—may have never left her. Hazzard’s public identity was fixed

in sepia: the controlled, upright force who wrote exclusively in longhand, who

recast the collapse of the twentieth century in an impeccable

nineteenth-century prose sensibility. But what emerges from a long view of her

life and work is that Hazzard’s traditionalism, if we can call it that, wasn’t

born out of unflagging allegiance to the past; it was a way to ground her own

explorations. Her most enduring characters were castaways, flung out to

unfamiliar territory; they saw the world as unmoored from its predicted

trajectory.

Her prose—unfurling, bedecked with clever literary allusions—smuggled in brutal hardships and kept them under her control. In Hazzard’s novels, soldiers starve in sodden forest prisons, men are swept away by biblical floods, children are orphaned and left alone in a ruthless world. She wrote about what was ugliest and most heartbreaking in the world and how it came to be that way; her talent was to make what surrounded it, including her own persona, elevated and graceful in equal proportion.

It’s curious that she started to write fiction at the exact moment she felt her life was finally hers—on the terrace of a sunny Tuscan villa at the heart of the European old world, supported by friends who recognized her brilliance, her ears filled with chatter about “politics, the pope, Piero della Francesca.” “Perfection, contentment, happiness,” she wrote in her diary. The beauty of the place, the “black and mighty … cypresses,” “geraniums fluttered by a light breeze,” and “pure, transparent, lemon-yellow” light, surely spurred her on. But so did the control over her life’s direction, the sense that she could now shape the bad and the good of her young life into the narrative she claimed for herself. At 24 she had written, “I am starved for affection and love and security and this makes me what I am.” Her subsequent feast on knowledge turned her into the writer she became.