In 2009, C-SPAN conducted a series of interviews with the Supreme Court justices about the judicial branch and its role in the U.S. constitutional order. Justices Clarence Thomas, Stephen Breyer, Samuel Alito, and Sonia Sotomayor all took part, as did the retired Sandra Day O’Connor. The most obvious participant was also the most unlikely one: Chief Justice John Roberts.

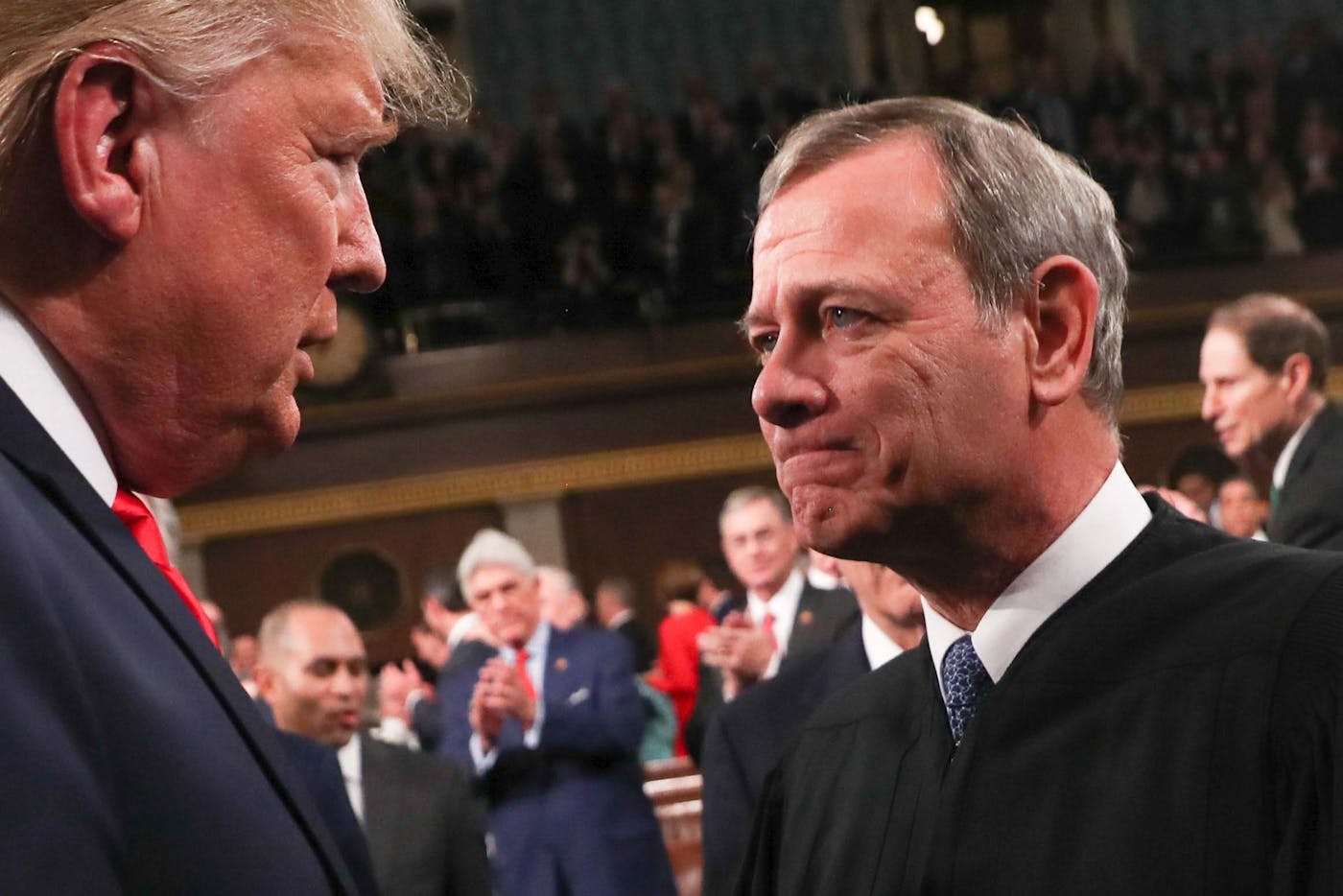

Roberts was, at the time, four years into what is now a 17-year tenure on the high court. Though he is nominally the leader of the federal judiciary, his public profile is practically nonexistent. Unlike Thomas, Sotomayor, and Breyer, he has never written a book. Unlike Alito or Justice Elena Kagan, he almost never gives speeches on the court’s work. And unlike Antonin Scalia or Ruth Bader Ginsburg, he has made no effort to establish himself as a prominent figure in the national consciousness. More than a few political reporters who covered the Trump impeachment trials, over which Roberts presided, said they had never heard his voice before.

As a writer and legal thinker, Roberts is characteristically lucid and direct. And as an interview subject for C-SPAN, he was equally straightforward. Host Susan Swain asked him what his fellow Americans should understand about the Supreme Court’s role in modern society. “The most important thing for the public to understand is that we are not a political branch of government,” Roberts told her. “They don’t elect us. If they don’t like what we’re doing, it’s more or less just too bad.”

Recent events have put that blunt assertion to the test. Over the last six years, just under half of the Supreme Court’s seats have changed hands. Three of the new justices were appointed by a president who received three million fewer votes than his opponent in the 2016 election and incited a mob to attack Congress to stay in power after the 2020 election. The court’s new ultraconservative majority wasted little time in putting its mark on U.S. constitutional law, culminating in the landmark decision to overturn Roe v. Wade this summer.

That ruling, in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization, appears to have been catastrophic for the Supreme Court’s standing among Americans. As recently as two years ago, 70 percent of Americans told Pew Research Center that they had a positive view of the Supreme Court. That number plummeted to just 48 percent in August. Driving the plunge was a collapse of support among Democrats (and Democratic-leaning independents): Where roughly two-thirds of them said they viewed the court favorably in 2020, now less than one-third of them were willing to say the same. A Marquette University Law School survey released in September found that a slim majority of Americans—51 percent—now favor expanding the court.

If there is one image that is often associated with Roberts, it is that of a baseball umpire. He made the comparison himself in his opening statement during his confirmation hearing in 2005, where he promised, “I will decide every case based on the record, according to the rule of law, without fear or favor, to the best of my ability, and I will remember that it’s my job to call balls and strikes, and not to pitch or bat.”

Roberts’s promise at the time to call only “balls and strikes” is often mocked by liberal legal figures who are skeptical of the conservative legal movement’s project to remake the U.S. judiciary—and with it, how the law and the Constitution shape our everyday lives. Roberts’s metaphor, however, was as much about humility as it was about fairness. Umpires “make sure everybody plays by the rules, but it is a limited role,” Roberts told the Senate Judiciary Committee 17 years ago. “Nobody ever went to a ball game to see the umpire.”

That last line is a good shorthand summary of Roberts’s tenure as the highest-ranking federal judge in the United States. His time as chief justice so far is defined by a steady rightward shift in the court, faster and deeper on some issues than others, with the chief himself often playing a starring role. But with the ascent of three Trump-appointed justices and the entrenchment of a six-justice conservative majority, Roberts has lost much of his influence over the future of the court’s jurisprudence. The remainder of the Roberts era may now instead be defined by a revolution that has outpaced one of its former leaders. Will the chief justice’s legacy now be a divided country and a discredited court?

Future historians and legal scholars will call this era of the Supreme Court’s history “the Roberts court” out of convenience and habit. Just as British historians refer to the Elizabethan and Victorian eras to capture a span of their history, or the French demarcate their eras since 1789 with five republics, two empires, and one Bourbon restoration, the longevity of many chief justices makes them a natural benchmark for legal history. Roberts has now been chief justice as long as or longer than just four of his predecessors, although he will not even reach the halfway point of John Marshall’s record-setting tenure—34 years, 152 days—until this December.

But naming eras of the court’s history after the chief justice can often obscure things as much as it clarifies them. Warren Burger, who served from 1969 to 1986, was not well respected by his colleagues and rarely led them in any meaningful way as the court transitioned from the heady, fading liberalism of the Earl Warren era to the ascendant conservatism of William Rehnquist’s tenure. Justice Potter Stewart grew so frustrated with Burger’s leadership that he served as the principal source for Bob Woodward and Scott Armstrong’s tell-all book about the court in 1979.

“The chief justice has one vote, which is no more, no less than any other sitting member of the court has,” Aziz Huq, a University of Chicago Law School professor, told me. “He has the ability to assign opinions if he’s in the majority,” Huq said. “He has something of an internal persuasive role, although I think it’s easy to overstate that. But certainly, the kind of public perception that he’s leader of the body, in the same way that perhaps the president is leader of the White House or the leader of the executive branch. Well, I think that that perception and implication when people use the term Roberts court is quite far off the mark.”

On many fronts, Roberts’s tenure has been a successful one for the conservative legal movement. Since he and Alito were nominated in 2005, the Supreme Court has recognized an individual right to bear arms in the Second Amendment and stripped federal courts of their power to hear partisan-gerrymandering cases. In First Amendment disputes, the court has diminished the Establishment Clause’s secular guarantees in favor a more muscular interpretation of the Free Exercise Clause.

For many movement conservatives, though, most of those victories were obscured by higher-profile defeats. Anthony Kennedy, who retired in 2018, regularly declined to use his fifth vote to overturn Roe sooner or dismantle affirmative-action programs in college admissions. Somewhat surprisingly, he provided a remarkable fifth vote that paved the way for almost every civil rights victory for gay and lesbian Americans over the past 30 years. The line of precedents culminated in his historic ruling in Obergefell v. Hodges, which struck down same-sex marriage bans nationwide.

In that case, the chief justice voted like Thomas, Alito, and Scalia. It also marked the first time where Roberts read his dissent from the bench to express his deep dissatisfaction with the ruling. “Five lawyers have closed the debate and enacted their own vision of marriage as a matter of constitutional law,” he wrote. “Stealing this issue from the people will for many cast a cloud over same-sex marriage, making a dramatic social change that much more difficult to accept.”

New Supreme Court justices can occasionally defy expectations from court-watchers and the public about how they’ll vote once they’re on the high court. But the chief justice didn’t fall into that category. “I think Roberts is one of the justices that the public perception of was exactly right, actually,” Benjamin Wittes, a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution and a journalist who once covered the Supreme Court, told me. “An institutionalist, a conservative, but not a far-right conservative. He is very traditional. He’s not interested in radicalisms, and he’s extremely polished.”

By most accounts, Roberts’s influence over his fellow conservatives began to wane in 2012. That spring, the court heard oral arguments on the constitutionality of the Affordable Care Act, the landmark health care legislation and the signature achievement of President Barack Obama’s domestic-policy agenda. At issue in National Federation of Independent Business v. Sebelius was whether Congress could constitutionally require most Americans to buy health insurance or pay a penalty for not doing so. Republicans denounced the individual mandate as tyrannical, while conservative legal scholars claimed that Congress had gone beyond what the Commerce Clause allowed it to do for interstate commerce.

The stakes were immense. Since the ACA lacked a severability clause, the court could not strike down one provision and leave the rest intact. Practically speaking, it was also thought at the time that the restructured health insurance system would collapse without the mandate to guarantee participation. None of the justices have publicly discussed what transpired behind the scenes while the opinion was drafted. But court-watchers have reported and surmised that, at some point during the deliberation process, Roberts changed his mind and decided that he would uphold the individual mandate.

When the court released its decision in the summer of 2012, many reporters initially thought that the law had been struck down when they read that Roberts, writing for a majority, had found that it violated the Commerce Clause. What they missed was the part where he went on to say that it was a valid use of Congress’s taxation powers, since the penalty for not complying with the individual mandate was collected by the Internal Revenue Service. The other four conservative justices made clear their deep opposition to the ruling with a rare joint dissent, one that reads like the majority opinion that would have been released but for Roberts’s reversal.

To say that conservatives outside the court were livid with Roberts’s perceived betrayal would be an understatement. “The Constitution does not give the Court the power to rewrite statutes, and Roberts and his colleagues have therefore done violence to it,” National Review complained in an editorial. “Justice Kennedy should be proud of himself for sticking to his principles, in light of Justice Roberts’ bullshit!” tweeted future President Donald Trump. “Congratulations to John Roberts for making Americans hate the Supreme Court because of his BS,” he later added.

Such past departures from conservative orthodoxy notwithstanding, it would be easy to overstate Roberts’s divergence from his colleagues these days. According to statistics collected by SCOTUSblog, the chief justice tended to vote with the other conservative justices between 80 and 100 percent of the time in argued and decided cases last term. There is some variance in those numbers—Roberts voted with Kavanaugh 100 percent of the time, while voting with Thomas only 78 percent of the time—but they still suggest that he often shares his two colleagues’ overarching philosophy. Roberts’s most frequent voting partner among the liberals last term was Justice Elena Kagan, and they voted together in only 63 percent of cases.

At the same time, there are signs that the court’s other conservatives have less confidence in and camaraderie with him than before. Earlier this year, after the leak of Alito’s draft majority opinion in Dobbs, Clarence Thomas spoke fondly of the “fabulous court” that he had joined under Chief Justice William Rehnquist. That bench was unusually stable, with the same nine justices working together from 1994 to 2005. “We trusted each other,” Thomas told an audience. “We may have been a dysfunctional family, but we were a family, and we loved it.” He noted that that period had ended after Rehnquist’s death in 2005, and most observers took Thomas’s time frame as an implicit jab at the man who took Rehnquist’s place.

“Roberts is just one of the nine, and except for some of his formal powers, I think he’s likely to be the loneliest of the nine, and I don’t think his personality is that of the loner,” Sanford Levinson, a University of Texas Law School professor, told me. “He’s not Scalia, or Thomas, who I think really loved writing lone dissents, or Rehnquist, who before he became chief justice wrote a fair number of lone dissents. I think that Roberts views himself more as a team player, and somebody who is skilled in putting together a functioning team.” And on the current court, Levinson continued, “He’s not that.”

There wasn’t always a gulf between Roberts and the right. In some ways, his legal career is a reflection of legal conservatives’ ascent: from the academic and political wilderness, to the first encounter with power during the Reagan revolution, and finally to entrenchment within the courts during George W. Bush’s presidency. And while the chief justice may not have embraced all of the movement’s priorities along the way, he has been resolutely firm on one of them: how the U.S. legal system thinks about race.

The conservative legal movement, contrary to some liberal caricatures, is not a monolithic body. The Federalist Society does not give marching orders to Republican-appointed judges or grow prospective Supreme Court nominees in giant vats in its basement. It is a collection of right-wing public-interest law firms; it is a social network of conservative and libertarian legal professionals; it is rooted in think tanks and law schools where adherents develop and refine their legal theories.

The movement itself is rooted in conservative reaction to the liberalism of the Warren court era, as well as a sense of exclusion from institutions where liberals were dominant. “One of the most important things that holds all this group together is they all have some, often different reasons, to have a problem with the American left, to find the left threatening to them,” Steven Teles, a political science professor at Johns Hopkins University who studied the conservative legal movement, told me. “Now they’re often threatening to very different things, and in some cases even mutually incompatible things. But they all have that same source, where the thing they care about most is threatened by liberal power.”

Roberts, a Buffalo, New York, native, had a taste of this when he attended Harvard as an undergraduate and a law school student in the 1970s. During his confirmation process in 2005, The New York Times spoke with classmates who described him as one of a handful of conservatives on a campus that was, at the time, predominantly filled with liberals and radical leftists. Roberts, by their account, was deeply informed by his conservatism but also showed a willingness to be persuaded by legal argumentation.

After graduating, he clerked first for Judge Henry Friendly, one of the most respected American jurists of the twentieth century, and Associate Justice William Rehnquist. After clerking for the future chief justice, he became one of the many young conservative lawyers who joined the Reagan administration in 1981. The Reagan Justice Department became home to lawyers who would shape the next few decades of the conservative legal movement, bridging the gap between its Nixon-era origins and its ascendancy in the George W. Bush years. While the movement’s early figures—Robert Bork, Antonin Scalia, and others—took federal judgeships, younger acolytes held other positions within the executive branch to make movement conservatism a legal reality.

At a Reagan Library event in 2006, Roberts described his work in this period by referring to Justice Robert H. Jackson, the middle-of-the-road liberal elevated to the bench by FDR and, interestingly, one of Roberts’s judicial heroes. “A particular story that [Jackson] liked to tell [was] of the three stonemasons. The passerby came upon three stonemasons all doing the same thing, and he asked the first one what he was doing, and the person said, ‘I’m making a living.’ He asked the second one what he was doing, and he said, ‘I’m laying those bricks according to this pattern.’ And he came to the third who was doing the same thing and he said, ‘What are you doing?’ And the man looked up and said, ‘I am building a cathedral.’

“Jackson’s point was one that was brought home to me when looking over these memos is that many, many mundane tasks go into great enterprises,” Roberts continued. “Many of us on the White House staff, maybe most of us, spent a lot of time doing very mundane things. We were laying an awful lot of bricks. But President Reagan never let us forget that what we were doing was building a cathedral, that we were part of a greater enterprise.”

Roberts’s portfolio at the Justice Department involved, among other things, the Civil Rights Division, which is tasked with enforcing federal voting rights and civil rights laws across the country. For almost all of Reagan’s administration, the division was headed by William Bradford Reynolds, a New England–born lawyer whose tenure focused more on narrowing civil rights laws than on enforcing them. Conservatives hailed him for steering the department away from what they saw as special treatment or non-neutral approaches to civil rights enforcement.

To his many critics, however, Reynolds was less of a friendly interlocutor on civil rights goals and more of a fierce adversary of them. “Either Mr. Reynolds doesn’t understand what civil rights is all about or he is not interested in the pursuit of equality,” Nicholas Katzenbach, who served as attorney general in the Johnson administration, said in a Washington Post profile of Reynolds in 1988. “Rights for Americans seems to him to mean rights for white males.” Citing Reynolds’s positions on those issues, the Senate Judiciary Committee rejected Reagan’s bid to promote him to the number three spot inside the Justice Department.

In the early 1980s, Congress debated reauthorizing and amending the Voting Rights Act of 1965. The VRA was among the most consequential pieces of federal legislation in the twentieth century, as well as a cornerstone of America’s full transition to multiracial democracy during the Second Reconstruction. One of the law’s core pillars, Section 2, established a nationwide ban on racial discrimination in voting laws. Members of Congress hoped to strengthen the provision to allow plaintiffs to sue over discriminatory election laws more easily.

That proposal drew some pushback from within the Reagan administration, with Roberts as the tip of the spear. In a memo for his boss at the time, Roberts laid out a case for opposing the changes. “The House-passed version of Section 2 would in essence establish a ‘right’ in racial and language minorities to electoral representation proportional to their population in the community,” he wrote. “Violations of Section 2 should not be made too easy to prove, since they provide a basis for the most intrusive interference imaginable by federal courts into state and local processes.”

Roberts’s argument was framed around the effects that the changes would have on the states and on elections, not on voters themselves who faced discriminatory laws and practices. “An effects test for Section 2 could also lead to a quota system in electoral politics, as the president himself recognized,” Roberts wrote in a memo for the attorney general, drawing upon familiar imagery from affirmative-action debates at the time. “Just as we oppose quotas in employment and education, so too we oppose them in elections.”

Another pillar of the Voting Rights Act was found in Sections 4 and 5. The provisions required some jurisdictions with histories of severe racial discrimination in elections to obtain approval, or “preclearance,” from the federal government before changing their voting laws or policies. This was strong medicine aimed to cure the nation—and especially the South—of Jim Crow voting laws. It worked, and voter registration rates in the South quickly climbed. Congress renewed the law most recently in 2006 by an overwhelming majority in the House and a unanimous vote in the Senate.

But even that historic vote in Congress was not enough to save it from the Supreme Court when Roberts got there. In a 2009 case that ultimately upheld preclearance, the chief justice suggested that the practice might no longer pass constitutional muster. That laid the groundwork for conservative legal activists to bring the challenge that resulted in Shelby County v. Holder in 2013. At oral arguments, the conservative justices framed the VRA’s preclearance provisions as a temporary measure that was no longer needed. Some members of the court suggested that they had to act because Congress itself would never overturn a law that was so popular—a remarkable inversion of how democratic systems are supposed to work. Antonin Scalia infamously referred to the Voting Rights Act as a “racial entitlement” during oral arguments, echoing Roberts’s criticism of the VRA amendments proposed in Congress nearly three decades earlier.

It was Roberts himself who wrote the majority opinion in Shelby County, claiming that the VRA’s preclearance formula had violated the “equal sovereignty” of the states. “Our country has changed, and while any racial discrimination in voting is too much, Congress must ensure that the legislation it passes to remedy that problem speaks to current conditions,” he wrote in his opinion for the court. Within 24 hours, multiple Republican-led states in the South said they would use the end of preclearance to pass new, more restrictive voter-ID laws.

Two cases this term will give Roberts another chance to extirpate considerations of race from U.S. constitutional law. In a pair of lawsuits brought by the conservative Students for Fair Admissions group, the court is expected to ban affirmative-action programs for college admissions. And in Merrill v. Milligan, the court could use a dispute over Alabama’s congressional districts to further narrow Section 2 of the VRA and make it harder to bring racial-gerrymandering claims in federal court. The conservative majority, with Roberts’s vote, already took steps to narrow Section 2 in Brnovich v. Democratic National Committee last year by giving states more latitude to pass restrictive voting laws.

The end goal appears to be a legal system that allows for virtually no consideration of race in public policy, even as a remedy for disparities and historical discrimination. Roberts himself summed up the approach in a 2007 case involving the Seattle school system, where the justices held that courts could no longer use race as a factor in school desegregation plans in almost all circumstances. “The way to stop discrimination on the basis of race is to stop discriminating on the basis of race,” Roberts concluded. Since then, Seattle schools have only grown more racially segregated. Roberts’s zeal to prevent what he saw as special carve-outs, whether in schools or elections, keeps him firmly anchored as part of the conservative legal movement.

So then why does the chief justice sometimes break ranks with his ideological kin in big cases? When explaining Roberts’s occasional tendency to vote against movement conservative interests, legal observers often describe him as an “institutionalist.” The chief justice is zigging instead of zagging, so the reasoning goes, to preserve public confidence in the Supreme Court as an impartial arbiter of the law. In this telling, Roberts is more consciously performing the role of the swing justice, so to speak, that moderates like Lewis Powell, Sandra Day O’Connor, and Anthony Kennedy performed as a matter of judicial philosophy.

“Everybody expected him to be very conservative,” Eugene Volokh, a UCLA School of Law professor who regularly blogs about the court, told me. “My sense is everybody also expected him to be somebody who really kind of wanted to maintain the reputation, institutional stability, institutional legacy of the U.S. Supreme Court. I think almost all chief justices do, but I think that was particularly clear from him.”

Some legal scholars, such as Huq, have questioned the label and pointed to destabilizing rulings like Shelby County as evidence to the contrary. Roberts has also notably never described himself as an institutionalist. If anything, he is publicly straightforward on the necessity for Americans to accept Supreme Court rulings as they are given. “If the court doesn’t retain its legitimate function of interpreting the Constitution, I’m not sure who would take up that mantle,” he said at a conference led by the 10th Circuit Court of Appeals in September. “You don’t want the political branches telling you what the law is, and you don’t want public opinion to be the guide about what the appropriate decision is.”

Legitimacy, at least when it comes to the Supreme Court, can be a tricky thing to quantify. Like any other judge or court, the justices aren’t strictly supposed to be in step with public opinion, even if the general expectation is that they don’t stray too far from it. Wittes noted that nobody is seriously talking about defying the court or ignoring its orders; most reform plans on the left instead hope to add more seats to it. “It’s his job to say those things and to stand up for his branch,” he told me, referring to Roberts’s 10th Circuit remarks. “His actions speak louder than his words, frankly.”

Those remarks drew some criticism from outside observers—and perhaps, at least implicitly, from some of Roberts’s colleagues as well. At a California lawyers’ group event a few days later, Sotomayor noted that when the court overturned long-standing precedents, there would inevitably be some “discomfort” in society. “When the court does upend precedent, in situations in which the public may view it as active in political arenas, there’s going to be some question about the court’s legitimacy,” she explained. Kagan, at a separate event at a university in Rhode Island, warned against the Supreme Court “wandering around just inserting itself into every hot button issue in America.”

Indeed, if NFIB v. Sebelius was the first breach in Roberts’s camaraderie with his fellow conservatives, then his recent handling of abortion cases may have been the ultimate one. The chief justice was not a friend of Roe v. Wade when he joined the court or for many years thereafter, and he consistently voted in cases to uphold abortion restrictions and narrow Roe’s scope. Starting in 2020, however, he began to deviate from that path. In 2020, he voted to strike down a restrictive Louisiana abortion law that was functionally similar to one struck down by the court in 2016, even though he had voted against it then.

Texas’s now-infamous bounty law, which allows almost anyone to sue anyone who “aids or abets” an abortion in that state for at least $10,000 in damages, revealed an even deeper fissure between Roberts and the other conservatives. Federal courts had routinely struck down abortion bans in the years before Roe was overturned. To get around this hurdle, Texas lawmakers structured the law to make it virtually impossible for anyone to challenge it using the typical causes of action in federal court. The result was a broad chilling effect on abortion access in the state—and a blueprint for nullifying what was then a federal constitutional right without a feasible way for the courts to prevent it.

Roberts, perhaps recognizing the broader dangers of this tactic, wanted the court to enjoin the bounty law while legal challenges against it unfolded, only to be outvoted. “I would grant preliminary relief to preserve the status quo ante—before the law went into effect—so that the courts may consider whether a state can avoid responsibility for its laws in such a manner,” he said in a dissenting opinion when the case reached the court’s shadow docket last September. But the court’s other five conservatives voted the other way and effectively nullified Roe v. Wade, at least for one state, roughly nine months before they finished the job.

Dobbs may represent the nadir—so far—of Roberts’s influence over his colleagues to steer a middle-of-the-road outcome. He argued for the court to decide the case on narrower grounds, upholding the Mississippi law but leaving the court’s abortion precedents largely intact. “I would take a more measured course,” Roberts declared. “I agree with the Court that the viability line established by Roe and Casey [which upheld Roe] should be discarded under a straightforward stare decisis analysis. That line never made any sense. Our abortion precedents describe the right at issue as a woman’s right to choose to terminate her pregnancy. That right should therefore extend far enough to ensure a reasonable opportunity to choose, but need not extend any further—certainly not all the way to viability.”

His fellow conservatives rejected both his outcome and his approach outright. “In sum, the concurrence’s quest for a middle way would only put off the day when we would be forced to confront the question we now decide,” Alito wrote for the court. “The turmoil wrought by Roe and Casey would be prolonged. It is far better—for this Court and the country—to face up to the real issue without further delay.” We are going to overturn Roe one way or another, Alito and his colleagues may well have thought, so why not do it today? The three dissenting liberal justices did not join Roberts, either; they chose instead to release a joint opinion that lamented the majority opinion while ignoring Roberts’s concurrence.

There are some indications that the outcome in Dobbs may not have been completely preordained. CNN’s Joan Biskupic, a veteran Supreme Court reporter, wrote in July that Roberts had tried to persuade some of his fellow conservatives, most notably Kavanaugh, to adopt the more incremental approach laid out in what became the chief justice’s concurring opinion. Those efforts were apparently serious enough that other conservatives on the court started talking: An April editorial in The Wall Street Journal warned that Roberts was lobbying the others behind the scenes. Then someone—a clerk, a court employee, or maybe even one of the justices—leaked a draft of Alito’s majority opinion to Politico. Roberts publicly denounced the leak the following day and opened an investigation into the unprecedented breach. According to Biskupic, the leak also firmly shut the door on any possible compromise from the chief justice.

Perhaps the most ominous aspect of the ruling was a concurring opinion written by Thomas. In it, he took aim at a broader assortment of constitutional rights beyond abortion. Under a doctrine known as substantive due process, the Supreme Court has previously ruled that certain constitutional rights exist even if they are not explicitly protected by the Constitution’s text or structure. This approach was part of the basis for the court’s abortion rights jurisprudence. It also influenced rulings that protect contraceptive access, sexual intimacy, marriage equality, and more.

Alito stated at multiple points in the court’s majority opinion that the Dobbs ruling did not itself unsettle any of those precedents. Thomas, writing in his concurrence, agreed but said the justices should unsettle them next. “For that reason, in future cases, we should reconsider all of this Court’s substantive due process precedents, including Griswold, Lawrence, and Obergefell,” Thomas explained. “Because any substantive due process decision is ‘demonstrably erroneous,’” he continued, “we have a duty to ‘correct the error’ established in those precedents.”

It remains to be seen whether the rest of Roberts’s colleagues are on board with “reconsidering” these rulings, or even if cases will be brought to the Supreme Court that could give them the chance. Though he strenuously dissented from Obergefell in 2015, Roberts does not appear to be dogmatically opposed to LGBT rights: He gave a sixth vote to Justice Neil Gorsuch’s landmark ruling in 2020 that extended federal workplace-discrimination protections to gay and transgender workers. And his abortion votes since 2020 also showed some deference to precedent in the face of a resurgent conservative bloc that sought to overturn them.

It may be more accurate to describe this upcoming era not as the Roberts court, but as something else. Perhaps it will turn out to be the Alito court, reflecting that justice’s role at the forefront of publicly defending the court on the shadow docket and in religious freedom cases, as well as for writing Dobbs itself. Maybe future scholars will label it the Thomas court for his role as the conservatives’ intellectual leader who had prepared for this moment for almost three decades. Some observers might even be tempted to call it the Leonard Leo court, in recognition of that Federalist Society official’s central role in nominating and confirming most of the current conservative members of the court.

The right’s successes, however, could produce a backlash from the left similar to the post–Warren court one that helped birth the conservative legal movement a half-century ago. “The history of the Supreme Court getting way out of step with public opinion is a history of the Supreme Court getting its ass kicked, not the other way around,” Wittes told me. “Everybody forgets this, but the famed court-packing battle which Roosevelt lost in 1937; but by 1939 and 1940, [those he had appointed] had taken over the court. There are some young people on the Supreme Court, but the actuarial tables never favor the longevity of any group of nine adults sitting together.”

Until then, Roberts will still ultimately be an active participant in conservative victories at the court for the foreseeable future, especially when it comes to race, religion, and regulatory power. But if the Supreme Court’s other conservatives are undeterred by the decline in public support for the court and eager to reshape Americans’ privacy and intimacy rights, then Roberts may be helpless to stop his colleagues from turning the institution into one of the most unpopular and revanchist iterations of the high court in U.S. history.