Call it a vibe shift, but after a year of relentlessly bleak news and polling that seemed to confirm that Democrats would suffer the traditional beatdown that the party in power tends to receive in the midterms, the summer has ended with a sense of optimism in the air. The economy may not be as bad as many feared. The party is getting things done. The Supreme Court’s ruling in Dobbs has proven to be massively unpopular. Republicans are overstepping. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine is failing. And relatedly, the polls have started to shift in a more favorable direction.

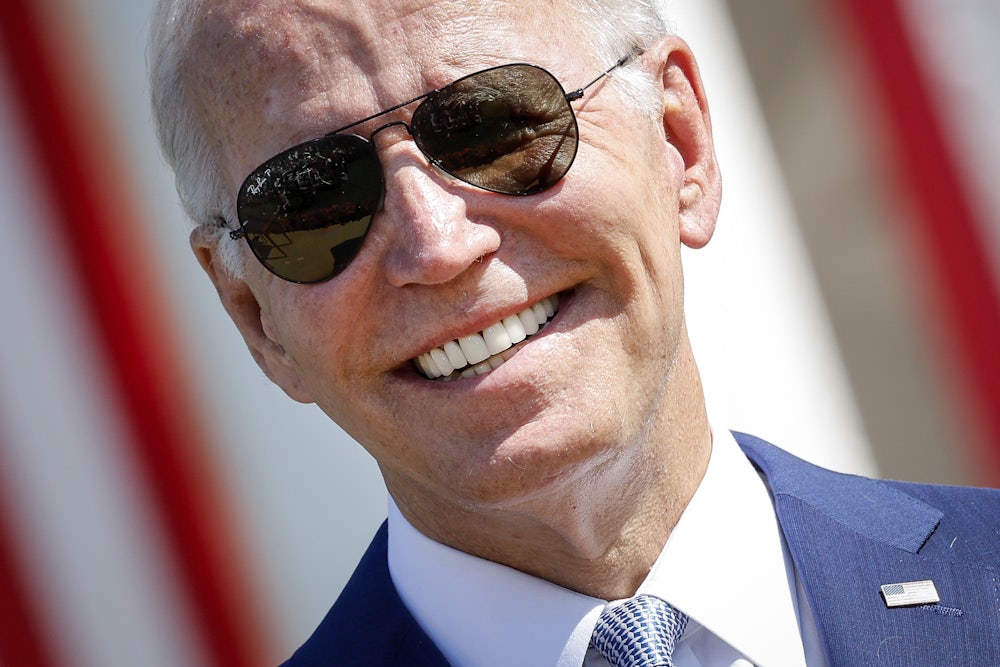

Democrats are performing shockingly well in the generic ballot, which gauges which party voters would like to control Congress, and are benefiting from a slate of weirdos and crazies being pushed by Donald Trump and Peter Thiel. And while they remain relatively dismal, even Joe Biden’s poll numbers have started to inch upward—though Democrats have tended to run ahead of his numbers. Democrats have slowly, if cautiously, found reason to believe that they can hold at least one chamber of Congress.

But let’s not forget that this is the Democratic Party we’re talking about: always ready to channel Chicken Little, especially when it comes to poll numbers. All those things that are going well—are they actually going a little too well? Maybe even suspiciously well? Wouldn’t it be wise to give in to a little pessimism?

It’s not unreasonable to be skeptical of the party’s recent change in fortunes. As Nate Cohn laid out in a recent piece for The New York Times, the polling errors that caused so much chaos in the 2016 and 2020 election have never really been fixed. “That warning sign is flashing again,” Cohn wrote, referring to a tool the paper used to handicap polls in 2020, which was created after noticing the polls during that election were flawed in similar ways to its predecessor. “Democratic Senate candidates are outrunning expectations in the same places where the polls overestimated Mr. Biden in 2020 and Mrs. Clinton in 2016.” The polls may be overcounting Democratic support—activated in part by the Dobbs ruling—and undervaluing Republicans, particularly inconsistent voters who were activated by Trump in 2016 and 2020. The result could be much like it was in 2016 and 2020, with polls showing Democrats leading in key races and states across the country, only for those leads to be revealed as a mirage on Election Day.

For Democrats, the scars of past elections run as deep as the stakes for 2022 are high. As Cohn notes, should a “2020-like polling error” materialize, the “Democratic edge in Senate races in Wisconsin, North Carolina and Ohio would evaporate.” For Republicans to retake the Senate, they would only need to win in two more states: Georgia, Arizona, Nevada, or Pennsylvania. Democratic leads in two of those states—Pennsylvania and Arizona—seem robust. But this isn’t the case in Nevada and Georgia. Given that Democratic chances to hold onto their slim majority in the House are already small, if not infinitesimal, polling errors could mean that Republicans are still on their way to retaking both chambers of Congress in the new year—the result that history teaches us to expect.

But there are tantalizing reasons to suspect these polling numbers aren’t a mirage—that this time, history may take a year off. One of the biggest boons that Republicans received in 2016 and 2020 was Donald Trump’s presence on the ballot: Some voters, it seems, really do only turn out to vote for their guy, a fact that often boosts downstream Republicans. There are, moreover, reasons to believe that Trump’s crown has slipped among some GOP voters amid a wave of scandals—the January 6 commission’s revelations, an FBI raid of his Florida residence, and the usual torrent of chaos coming from rallies and his (admittedly obscure) remaining social media account. Trump’s likely reemergence as the midterms draw nearer may inspire some voters, but it may just as likely suppress turnout among other Republicans, while inevitably reminding certain Democrats of the importance of turning out in November.

Beyond that, the wave of good news for Democrats also isn’t a mirage. The party is enjoying a mix of real political success and some genuine lucky breaks; the gains are real. While Tuesday’s news on inflation was much worse than anticipated, gas prices have continued to fall. Concerns about the country lurching into a recession have abated. Wages are rising, and employers are hiring: Biden’s getting the labor market he wanted. Democrats are passing legislation and, crucially, have also done two things that speak to the concerns of many young voters: pass a bill that fights climate change and provide some student debt relief.

Republicans haven’t been able to associate themselves with big political wins or favorable material conditions. The continued revelations surrounding the January 6 insurrection serve as a steady reminder of the growing authoritarianism of not just Trump but the Republican Party. Most importantly, the Dobbs decision has turned abortion into one of the most pressing issues in the midterm elections. There’s no telling whether all of this will lead to big voter turnout among Democrats in November. But what is undeniable is that none of these conditions were present six months ago.

As my colleague Walter Shapiro noted in Roll Call, the idea that Democrats might hold onto just one chamber of Congress seemed unrealistic not long ago, as all the “smart political handicappers were prophesizing a Republican tsunami.” But if Democrats needed a staggering amount of luck to have a chance, since the latter half of June, luck has broken their way. It may not be enough good fortune to hold onto both chambers; all hot streaks eventually come to an end. Wariness around polls—particularly after Democrats got burned in 2016 and 2020—is sensible. But if there was ever a time for a “this time it’s different” election to happen, you couldn’t do better than right now.