Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen traveled to Poland this week to urge support for a 15 percent global minimum tax on corporate income. These negotiations are slow going, but the Poles will be pushovers compared to the United States Senate. The same Senate Republicans who wish to impose a minimum income tax on people refuse to impose one on corporations.

“All Americans should pay some income tax,” says Senator Rick Scott of Florida, chairman of the National Republican Senatorial Committee, in his Rescue America plan. In practice, that means someone making, for example, $30,000 annually should pay the IRS more than $1,000 in income tax. A thousand bucks is an awful lot of money to someone living on $30,000 a year. But it’s necessary for this person to pay something, Scott insists, so that he or she will “have skin in the game.”

It’s a matter of behavioral conditioning—Pavlov’s dogs, B.F. Skinner’s box, that sort of thing. Without skin in the game, the editorial board of The Wall Street Journal explained 20 years ago (“The Non-Taxpaying Class”), people who are too poor to pay income tax become “that much more detached from recognizing the costs of government.” (Never mind that our friend making $30,000 already pays $2,295 annually in Federal Insurance Contributions Act tax to pay for Social Security and Medicare.) Instead, this person thinks of the government merely as an automated teller machine that spits out food stamps and welfare checks.

Should all American corporations pay income tax, Senator Scott? They don’t right now. A report by the nonprofit Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy that is cited a lot by President Joe Biden identified 55 large corporations, more than 10 percent of the S&P 500, that paid no income tax in 2020. These included FedEx, Nike, and Archer Daniels Midland. A report by the congressional Joint Committee on Taxation that sampled tax returns from 50 large corporations covering the years 2014 to 2018 found the percentage that paid no income tax was more like 20 percent.

Applying Scott’s logic, and that of the Journal’s editorial page, FedEx, Nike, and Archer Daniels Midland don’t have skin in the game. Ten to 20 percent of the biggest corporations in America have become “that much more detached from recognizing the costs of government.” Instead, they think of government merely as an automated teller machine that spits out accelerated depreciation schedules and opportunity zone tax credits.

Yet Scott and the Senate GOP’s Rescue America plan make no mention of President Joe Biden’s proposed minimum income tax on corporations; the Journal’s editorial page fervently opposes it; and various Senate Republicans pledged to oppose it, too. Senate Republican leader Mitch McConnell called it a “red line.”

The ranking members of the House Ways and Means Committee and the Senate Finance Committee, Representative Kevin Brady of Texas and Senator Mike Crapo of Idaho, wrote Yellen last June about the minimum corporate tax. “Other countries have shown that they will aggressively seek to gain market share and strip away our tax base,” they said. “The administration should not surrender jobs, growth, or tax revenues to other countries in order to advance a partisan tax increase agenda at home.”

That was grandstanding. As Brady and Crapo well know, the minimum corporate tax proposed by the Biden administration is a global minimum worked up by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development to halt an international arms race of tax cutting. A corporate minimum tax is necessary precisely because tax havens are slashing tax rates to attract U.S. corporations. In 2017, President Donald Trump entered this game of limbo by dropping the top corporate tax rate from 35 percent to 21 percent.

Before we proceed, allow me to share a couple of charts from a 2020 report by Harvard economist Jason Furman for the Brookings Institution’s Hamilton Project.

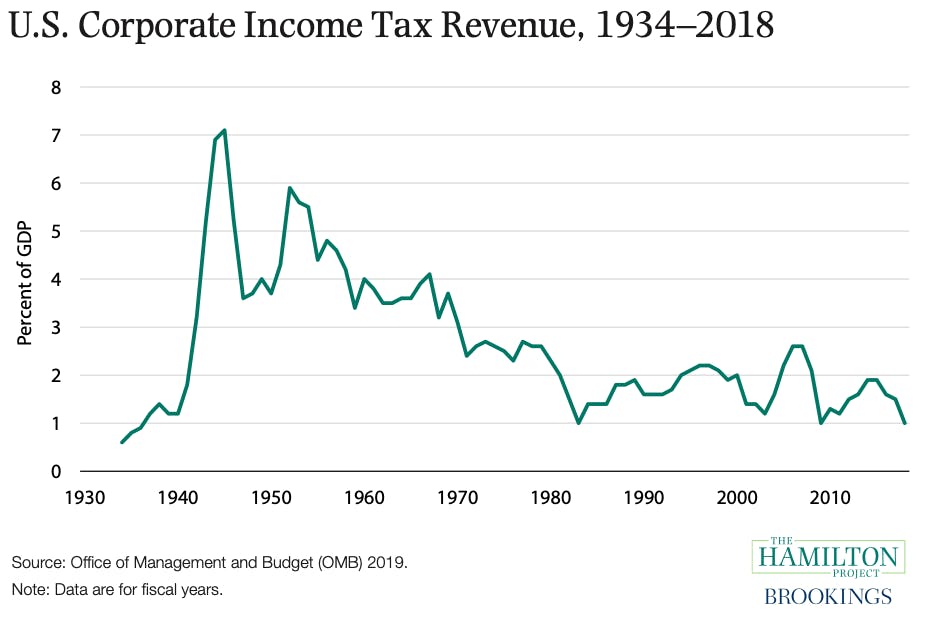

The first chart shows revenue from the U.S. corporate income tax since 1930 as a percentage of gross domestic product. Note its downward slope. Corporate taxes, Furman writes, “are less than half their historic average.”

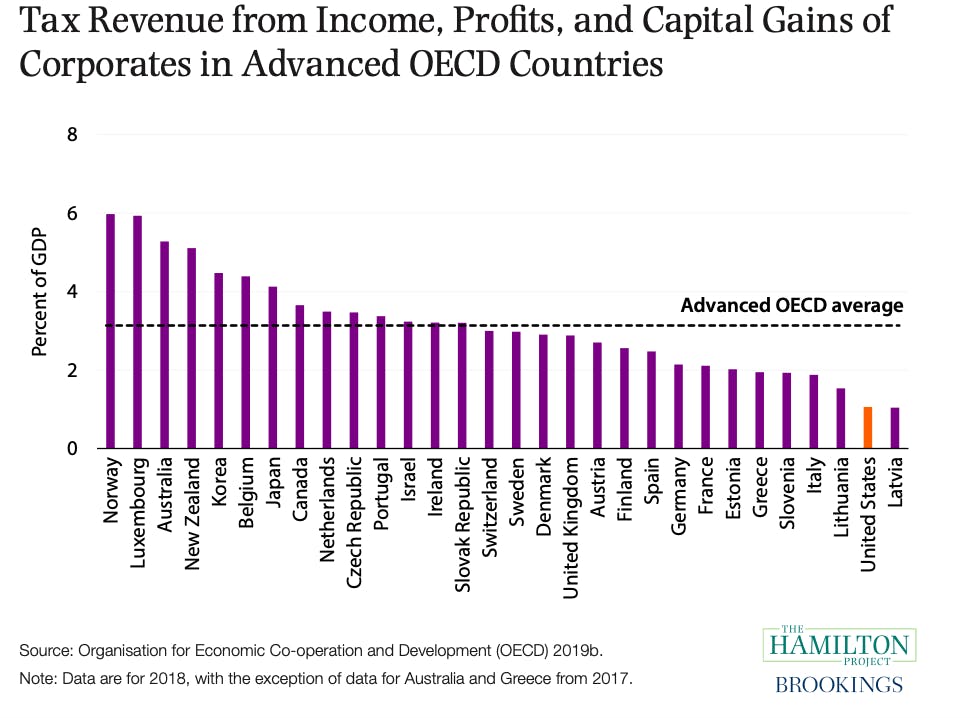

The second chart compares tax revenue from U.S. corporations, as a share of GDP, to that in other advanced industrial democracies. Even before the 2017 tax cut, the effective corporate tax rate in the U.S. was, when you figured in various exemptions and deductions, about the same as in other comparable nations. But as a share of GDP, it wasn’t about the same; it was way behind—indeed, one up from dead last, just ahead of Latvia.

Don’t let anybody tell you corporate taxes are high in the U.S. By historic standards and by international standards they are very, very low. As Scott would say (but doesn’t), corporations don’t have a lot of skin in the game.

Unlike Scott’s anxieties about the working poor who don’t pay income tax, the shortfall of corporate tax revenue is not an abstract concern. Low corporate tax revenue is a major reason why the U.S. Treasury is starved for cash. In 2018, Furman observed, overall tax revenue for the federal government was, omitting cyclical downturns, at a 50-year low relative to GDP. And that was before Congress spent $4 trillion on Covid relief (most of it on a bipartisan basis).

There are two reasons for the downward trend in corporate revenue. One is that tax havens like Bermuda and the Cayman Islands have much lower tax rates (or, in the case of the Caymans, no corporate income tax at all). Hence the OECD proposal for a 15 percent minimum corporate income tax. As Yellen’s Poland trip shows, there remain some obstacles abroad to implementing the minimum tax. But after the G-7 nations endorsed it last year, 130 nations, representing more than 90 percent of global GDP, signed on, including, in principle, Poland. Even the Caymans signed on! Congressional Republicans, by contrast, won’t endorse an international minimum even in principle.

The second reason for the downward trend is that tax laws, both here and abroad, make it laughably easy for corporations to lower their tax bills by allocating profits to foreign tax havens. Before the Trump tax cut, this practice cost the Treasury more than $100 billion annually, according to congressional testimony last year by Kimberly Clausen, deputy assistant secretary for tax analysis at the Treasury Department. The loss was less after the Trump tax cut, but only because the U.S. corporate tax rate was lower.

The 2017 tax cut included a couple of provisions intended to reduce profit-shifting, including a tax on intellectual property and other “intangible income” when it’s assigned to other countries. But the 2017 law also included a couple of other provisions that made profit-shifting easier. The net result, Clausen observed in her testimony, was that the share of U.S. corporate income in the seven biggest tax havens (Bermuda, the Caymans, Ireland, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Singapore, and Switzerland) remained about the same after the 2017 law was enacted.

The OECD plan would go after the profit-shifting problem more aggressively, in part by shifting tax jurisdictions to places where customers actually reside, which is mostly in wealthier nations with higher corporate tax rates. Because it’s more complicated, the details of the profit-shifting proposal are taking longer to produce. They will also be harder to implement, because they’ll require alterations to various existing international treaties.

In the U.S., that poses the biggest obstacle. At least in theory, the 15 percent minimum corporate tax can be folded into a reconciliation bill—it was included, for instance, in the Build Back Better bill—and therefore would require only 51 votes in the Senate. But the profit-shifting changes alter U.S. treaties and therefore require 67 votes in the Senate.

Don’t Republicans want corporations to pay their fair share? Not on your life. If anything, Republican opposition is hardening. “I certainly hope that the deal does not get implemented by the U.S.,” Crapo told Bloomberg reporter Laura Davison on Wednesday. “That would be a terrible mistake.” Corporations don’t want to pay a minimum income tax, and therefore Senate Republicans (and, to be fair, a few Democrats) don’t want to impose one. I doubt your cleaning lady wants to pay a minimum income tax, either. But as far as Senate Republicans are concerned, she’ll just have to suck it up.