There is a certain type of reader who, working her way through Proust, can think only of her own most recent heartbreak. She might be shy and bookish; certainly she is young. This reader might of course just as easily be a sad, literary boy, finding his ex refracted back to him in Goethe or Henry James. Nowhere are such readers easier to find than on college campuses, where heightened romantic sentiment and intellectual discovery are intertwined, and where people still in the process of forming a sense of self can meet, read the same books, talk about them at length, fall in love, break up, and then look for themselves in the pages of other books.

Selin in Elif Batuman’s new novel, Either/Or, reads in just this way—to learn about herself. For Selin, everything is laden with possible meaning. Entering her sophomore year at Harvard, she happens upon a class called “Comp Lit 140: Chance,” in which students are to consider artists inspired by the unexpected and unbidden. They will study the figure of the flâneur, who finds meaning in wandering the streets; they will read works of surrealism, including Andre Breton’s novel Nadja. The class and its syllabus strike her as if designed solely for her. Her boyfriend Ivan had, after all, gone to California to study chance itself! His thesis “was about random walks!” And they had bonded over a line from Nadja!

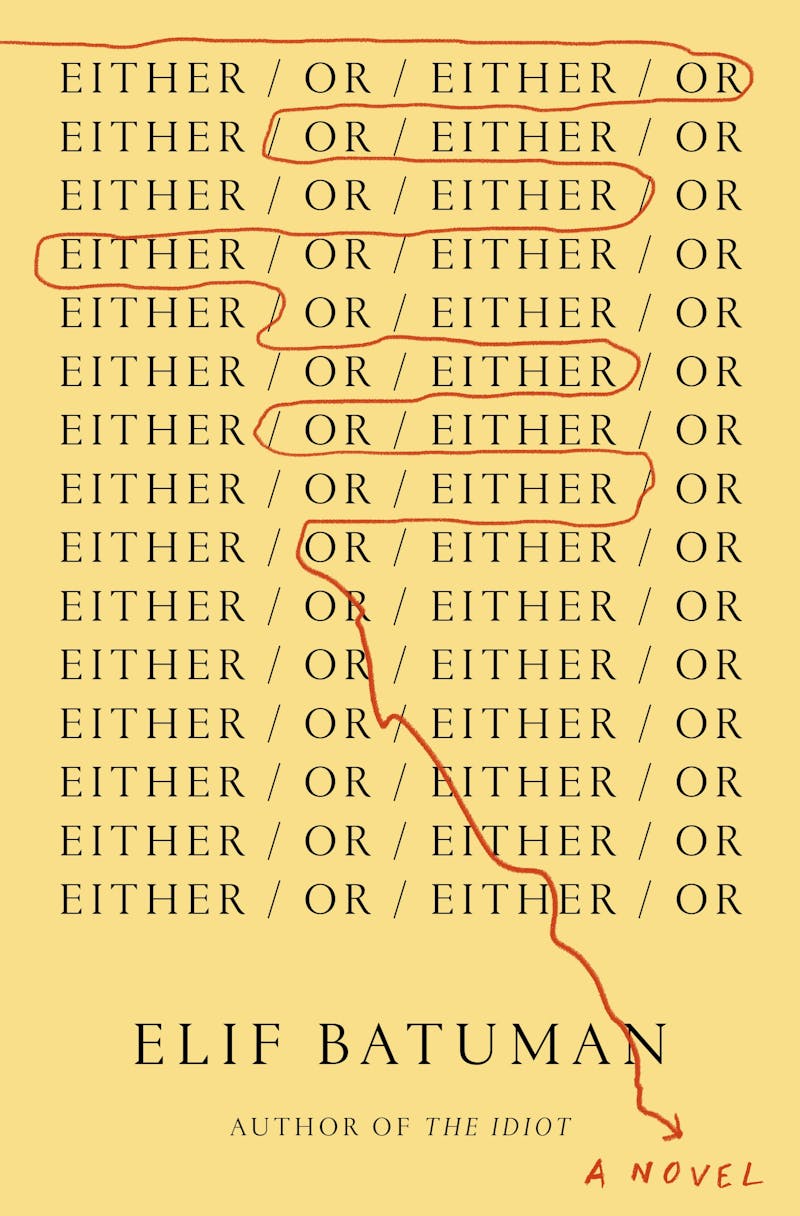

As it happens, one of Batuman’s abiding preoccupations is how literature intersects with life. She has expressed a general preference for nonfiction over contemporary fiction, for its ability to engage with reality. “Non-fiction is about some real thing in the world,” she wrote in the London Review of Books in 2010. “It’s about real people and real books, which are, after all, also objects in the world.” The novel, she proposed, should “expand to include these things, which were once—in Don Quixote, for example—a part of its purview.” Her writing has straddled the two categories: Her first book, The Possessed, was nonfiction, a collection of essays studded with her personal experience, while her first novel, The Idiot, included passages of literary criticism and its narrative bore a strong resemblance to the actual events of her own life as a Harvard freshman in the mid-’90s—like its narrator, Selin, she traveled to Hungary in the summer and had a deep affinity for Russian literature. Literature should be like life, which is also steeped in literature. But then what?

In Either/Or, Selin is now a sophomore, still reading constantly, still overidentifying. And yet suddenly more is happening to her. In writing Selin, Batuman seems to be puzzling out what differentiates a novel from a description of a consciousness reading and thinking and accumulating knowledge. Much contemporary fiction works on the assumption that thought and critical engagement are enough to make a novel work, and that formless, plotless days strung together cerebrally are enough. But Batuman doesn’t seem so sure, and indeed this novel feels like an experiment with eventfulness. We wonder, reading about Selin: Do people have to fall in love and have sex for a novel to work, or can it be more like an extended reading list? Do things have to happen, and if they do, what can we make of them?

The Idiot, published in 2017, was a novel about things not happening. It focuses on Selin’s friendship with a girl named Svetlana and her intense, unconsummated relationship with a senior named Ivan. She spends the summer of her freshman year teaching English in the Hungarian countryside, in some ways a period of uneventful drifting. She describes her experience there as a bit like that of reading War and Peace: “New characters came up every five minutes, with their unusual names and distinctive locutions, and you had to pay attention to them for a time, even though you might never see them again for the whole rest of the book.” She rarely sees Ivan, who is in Budapest. Instead they exchange emails, a tortured and high-minded correspondence that forms the core of the book. (These include poetic non sequiturs that Selin tries to close-read like a code: “From your message, I figured out what happened: the snow fell the wrong way (up), slowly until it all disappeared. This is fine if the fresh grass does not hide back in the earth, and what comes is Hello Spring, not Goodbye Summer. Not that again.”) At the end of the novel, Selin has still never been kissed.

Either/Or picks up more or less where The Idiot left off, Selin’s suitcase rattling across cobblestones as she returns to campus after her summer in Hungary. The novel has the same wry tone—with Selin as a conduit for Batuman’s brilliant, funny observations—but it is characterized by a shift: Selin is ready to stop thinking about living and start doing it. An early section, titled “Some Things Svetlana and I Talked About,” consists largely of questions. What would an orgy be like? What is the worst cruelty: personal or political? Are equal relationships possible? Though Selin attends no orgy, there is a sadomasochism-themed party at the literary magazine. (“One particularly tedious editor had a plastic ball strapped in his mouth, but kept taking it out to talk, so then he just had this saliva-covered ball hanging around his neck.”) And while she does not find an equal relationship, she does enter into a variety of new relations with different notions of what equality could be.

For all the activity in Either/Or, however, there still doesn’t seem to be much shape to these events. There’s a plotlessness to Selin’s sophomore year: She goes to party after party. She loses her virginity. She begins drinking alcohol, more or less on a whim. Sometimes Selin’s pursuit of experience feels a bit like her attitude toward philosophy, or learning Russian; she seems to do things in the spirit of intellectual inquiry rather than on impulse. When she loses her virginity, it’s because she decided that it’s past time. When the story starts to come together, it’s through a fluke: At one point, Ivan’s ex-girlfriend logs onto his email; Selin assumes it’s Ivan, so the two of them begin to talk over instant message and the phone, with Zita telling Selin the whole story of her own relationship with Ivan and a love triangle. The interaction feels cosmically charged, a technological mishap of great consequence, but what’s the point of it?

In the absence of a major plot line, Selin goes on a physical journey. In something of a repeat of her freshman summer, she travels. She goes to Turkey, where both her mother and father grew up, though she works as a guidebook writer—a quintessential observer-participant, experiencing things for the sake of recounting them to others. She ambles through the world, meeting people and doing things for reasons that are not particularly clear, other than that she has been assigned to do them. On her travels, there is a whole succession of men and it’s hard to tell who might turn out to be important (the answer is basically no one and everyone—they all fall away, but leave traces). All of this is something like what her chance professor might have called “accretions of chance, randomly piled up, like the cigar ashes that only Sherlock Holmes could parse.”

Batuman seems to be self-consciously piling up these cigar ashes, making things happen to Selin in this “constructed world”—the name of another class Selin takes. This pulling of the strings is, of course, any fiction writer’s mandate, but it stands in contrast to the way that The Idiot was built mostly around the life of the mind, distanced from the mechanisms of the conventional romantic plot, even as it flirted with them. Either/Or might seem less strange at first glance—plotted as a more straightforward story of a young woman coming of age and finding herself—but it is arguably a more unusual work in its attempt to hold onto both this conventional plot and its literary critical bent.

By the end of Either/Or, I found myself wondering if there’s a difference, anyway, between the things we read and the things we do. Reading is an experience, if an artificial one, constructed and simulated—but then so are many of the others we go out in life to achieve in vaguely artificial ways. Selin is always coming back to her texts. Pining for Ivan, she memorizes Tatiana’s letter in Eugene Onegin for Russian class, and ponders how “from an early age, I had seen women I was related to, like my aunts and my mother, prostrated by suffering because of men.” After Ivan, she meets a distant Polish boy she comes to think of as “the Count,” after a Polish character in Iris Murdoch’s novel Nuns and Soldiers, whom the English characters all call the Count because they can’t pronounce his name.

The ending of The Idiot feels like a kind of trailing off, a stepping out of the romantic plot rather than succumbing to it. Either/Or, too, has an ending that we might deem “unsatisfying”—not so much really happens, and Selin is about to begin another journey, this time to Russia alone. And yet unlike The Idiot, there is a feeling of culmination: a plot brought to an operatic climax. Selin has a realization about how art and life are intertwined, one that feels like a “decisive moment” in her life—even as she is simply reading Portrait of a Lady on an airplane.

Experiences or events may not matter in and of themselves but rather because of the way they intersect in this specific consciousness. Maybe the novel can be as plotless as life and still hang together; maybe it can be both a reading notebook and a quest. The dramatic close of Either/Or, after all, is not a big event but a shift in Selin’s mind that would be imperceptible, except that it has been rendered to us as seismic, something big happening in someone’s head.