Speaking at the annual meeting of the Association of American Publishers on Monday, AAP president and CEO Maria Pallante addressed what may be the most pressing issue facing publishers in 2022. It “would hardly be a meeting of publishers,” she said, “if we didn’t address the First Amendment.”

“As we all know, across the country, thousands of books are being questioned with a scrutiny that’s newly chilling,” she said, per a report from Publishing Perspectives, “from novels to math books. This is not to say that parents and communities don’t have a say in public education, as the law is clear that they do. But that role has constitutional limits. It does not extend to capricious actions that cross the line and amount to censorship. In fact, the line is important.”

Michael Pietsch, CEO of Hachette—one of the “Big Five” publishers—and the AAP’s current board chair, largely concurred. “There are fires raging in our industry, and in the world at large,” he said. “We’re confronting many serious issues—what I would say is the biggest set of simultaneous challenges our industry has faced in a generation.”

“Not just a global virus but also sensational and outrageous book bans, an unprovoked war in Ukraine, unprecedented supply chain disruptions, a persistent shortfall in diversity in our offices and publishing programs, climate challenges, and unrelenting efforts to weaken the copyright framework that has protected and promoted publishing since the earliest days of the nation,” he continued.

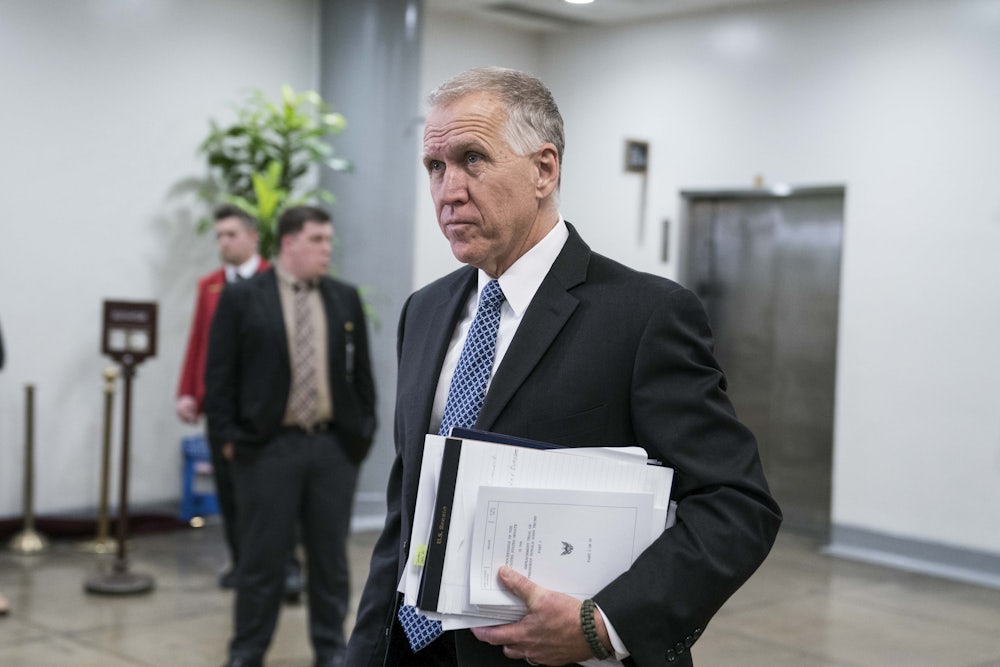

This is a tricky set of priorities in this age, one balancing the necessity—and politics—of the moment on issues like race and censorship with the typical concerns of a trade group. Nevertheless, the AAP’s delicate balancing act seemed to come completely undone during this most recent meeting. When it was time to hand out an accolade for Distinguished Public Service, the group chose to honor Senator Thom Tillis. What is the case for Tillis? Well, on the one hand, the North Carolina Republican is a copyright hawk who is co-sponsoring, with Vermont Democrat Patrick Leahy, a new copyright law that the AAP is backing vociferously. However, on the other hand, Tillis is also the co-sponsor of another bill, one that as reporter John Maher pointed out on Twitter earlier this week, would “prohibit the use of federal funds to teach the 1619 Project by K-12 schools or school districts.” The First Amendment, in other words, was the second banana.

The AAP’s Distinguished Public Service award has gone to political figures before. Democratic Senator Amy Klobuchar received the honor last year, in part for her efforts fighting economic concentration (she took the moment to, among other things, decry consolidation within the publishing world). Former Republican Congressman Doug Collins, who subsequently made unfounded claims of voter fraud in the 2020 election, is a previous recipient, while Bob Goodlatte, who was previously most famous for gutting the Independent Ethics Office, has been retained as a lobbyist by the Association of American Publishers for several years and has already been paid $40,000 in 2022 by the organization per data from Open Secrets.

The award for Tillis is narrowly focused on what the AAP deems his “outstanding contributions to the public good by advancing laws or policies that respect the value, creation and publication of original works of authorship.”

“Throughout his tenure as Chair and Ranking Member of the Senate Intellectual Property Subcommittee, Senator Tillis has been a steadfast supporter of the copyright framework that is foundational to an informed and inspired society,” Pallante said in a statement. “He has elevated the discussion of copyright issues in important and meaningful ways because he understands that authors, artists, publishers, and producers are essential to the public interest and our modern global economy.”

There is no mention, at any point, of Tillis’s efforts to block federal funds being used to teach the 1619 Project in public schools. This is perhaps especially notable because the CEOs of all “Big Five” publishers—Penguin Random House, Hachette, Macmillan, HarperCollins, and Simon & Schuster (which is on the verge of being acquired by Penguin)—all sit on the group’s board, and Markus Dohle, the CEO of Penguin Random House, published a bestselling book edition, The 1619 Project, which first appeared in The New York Times. (Representatives from PRH and the AAP would not comment on the record for this story.)

The AAP tends to switch between honoring Democrats and Republicans—a typical move for an industry group whose primary focus is its own economic well-being. Copyright policy is understandably among the group’s most important priorities; pro-business Republicans like Tillis and Goodlatte are valuable allies. And yet by honoring them, the industry also cheapens its stated commitment to fighting censorship and supporting diversity. Instead of pushing Tillis on the matter of First Amendment protections, the AAP has opted simply to ignore the parts of his political profile that go against its professed values. It’s dispiriting but not unsurprising: Even after the tumult of the last two and a half years and the rancid ideology that’s driving this next great wave of book banning, the publishers only have eyes for their balance sheets, only paying lip service to their supposedly deep commitment to free expression.

Publishers have long cast themselves as protectors of the First Amendment and have in recent months organized initiatives to push back against the book bans that have gone into effect on works relating to race, gender, and sexuality across the country. The AAP itself has recently filed an amicus brief challenging the removal of books from libraries in one Missouri school district. But the industry often falls short on the kinds of standards to which it would hold others—diversity in hiring practices and salaries have been vexing labor issues that publishers have only recently started to address. Naturally, the industry has a vested interest in protecting its bottom line as well: The AAP, in particular has advocated for strengthening copyright protections and updating the Digital Millennium Copyright Act; it argues that not enough is being done to protect intellectual property in the internet age.

Handing Tillis an award he plainly doesn’t deserve is just part and parcel with the larger tumult that has engulfed the publishing industry. Over the last five years, but particularly since the end of the Trump administration, publishers have tried to walk a fine line, decrying authoritarian efforts to subvert American democracy, attempting to live up to stated values about diversity and free expression, while also continuing to publish—and profit from—books by figures who are increasingly opposed to those values. The result has been an awkward dance, one in which the industry is constantly grandstanding about its civic commitments while violating their spirit anytime its profits are on the line.