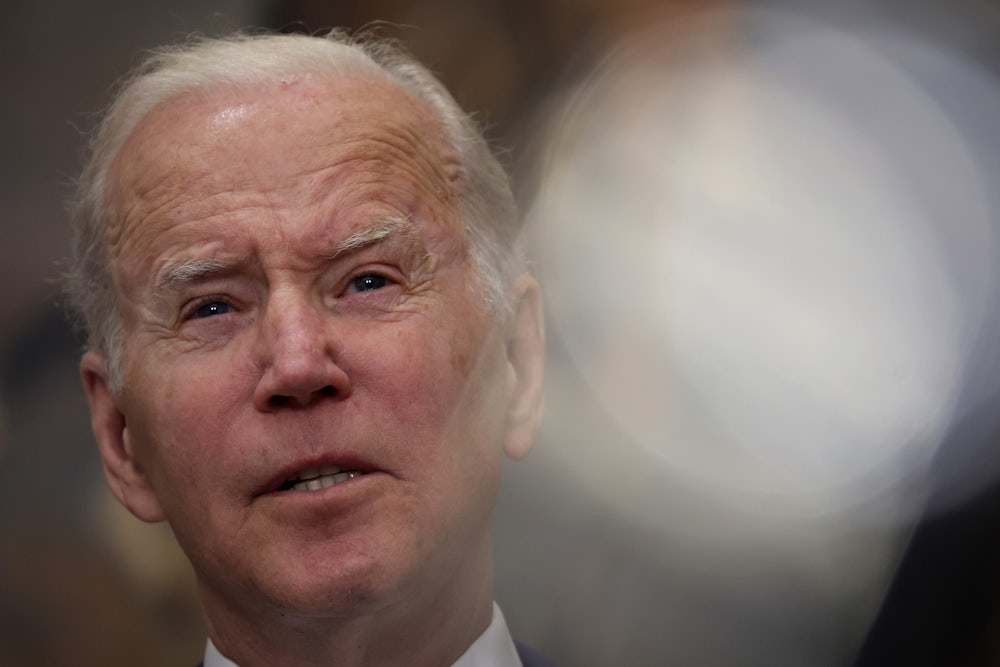

If the Supreme Court follows through with its plans to overturn Roe v. Wade in the next two months, what could President Joe Biden do about it? The short answer: not much. Biden has no power to countermand a Supreme Court ruling on abortion, and he cannot rewrite the flurry of state laws that seek to effectively outlaw the procedure.

That hasn’t stopped the administration from thinking about ways to push back. In a statement on Tuesday, after Politico published Justice Samuel Alito’s first draft of Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization, Biden claimed he had unspecified “options” to use if the court overturns Roe. “Shortly after the enactment of Texas law S.B. 8 and other laws restricting women’s reproductive rights, I directed my Gender Policy Council and White House Counsel’s Office to prepare options for an administration response to the continued attack on abortion and reproductive rights, under a variety of possible outcomes in the cases pending before the Supreme Court,” he said on Tuesday. “We will be ready when any ruling is issued.”

What those options might entail isn’t yet known. The White House Gender Policy Council does not have any lawmaking or regulatory power, though it could advise Biden and the White House counsel’s office on potential policy steps they could take. But some reproductive rights advocates have nonetheless laid out ways that the Biden administration could concretely push back against the overturning of Roe. With this week’s historic leak, calls for aggressive action likely will grow.

The most forceful response would be a legislative one. Some Democrats have renewed calls for legislation to codify Roe at the federal level. In theory, that could preempt state laws that severely restrict or ban the procedure. The House passed the Women’s Health Protection Act last September, which would supersede a wide range of state-level restrictions, but it failed in a 46–48 vote in March. Maine Senator Susan Collins and Alaska Senator Lisa Murkowski introduced the Reproductive Choice Act in February to pursue that same goal more narrowly. It would simply require states to follow the undue-burden standard that currently exists.

Both bills stand almost no chance of becoming law even if Roe falls this summer. Not enough Republican senators would support either bill to overcome a filibuster, and Democratic Senators Joe Manchin and Kyrsten Sinema have said they wouldn’t nix the filibuster to pass them. Even if the bill could get through Congress and receive Biden’s signature, it’s also doubtful whether the Supreme Court would, when Republican-led states inevitably sued to challenge the law, uphold it as a valid exercise of Congress’s powers. The court’s 6–3 conservative majority is already skeptical of federal power over the states and is generally hostile to abortion rights.

With Congress unable to achieve anything significant, that just leaves Biden with the usual grab bag of executive powers. Alito’s draft opinion signals that the court will leave abortion laws to the states to decide, which in practice means that the procedure will be mostly or wholly unavailable in at least half of the states. Without Roe and Planned Parenthood v. Casey establishing a constitutional right to obtain an abortion, Biden and the Justice Department likely won’t be able to intervene when states start enforcing their restrictions, as they tried to do last year when the Justice Department sued Texas over its bounty law.

That does not necessarily mean that the Biden administration will be powerless to protect access to abortion in the restrictive states. But it does mean that the White House will have to be a little imaginative about it. Three law professors—David S. Cohen, Greer Donley, and Rachel Rebouché—have argued that the federal government could use its powers creatively to expand access to abortion, even in states that are otherwise hostile to it. In a New York Times op-ed last December, they urged Biden to rely on the general primacy of federal law over state law.

Perhaps the most efficacious area where the Biden administration could intervene is on abortion pills. One of those drugs, mifepristone, is approved by the Food and Drug Administration for abortion, but its use is further restricted by more than a dozen states. There are precedents, the professors argued, for the government to intervene. “When Massachusetts attempted to regulate a new opioid more stringently than the FDA did, a court invalidated the law because it was inconsistent with the purpose underlying federal drug law,” the three law professors argued. “If Roe is overturned, federal pre-emption may even provide a way to challenge general state abortion bans, to the extent that they effectively prohibit the sale of an FDA-approved drug.”

Their proposals do not begin and end with mere legal challenges. One of their more assertive proposals is for the Biden administration to “lease federal property to abortion providers—for instance, allowing a clinic to operate out of a federal office building or a mobile clinic on federal land.” In many circumstances, state governments have far less power to regulate and enforce their own civil laws on federal property. The professors noted in a recent unpublished law-review article that while the Assimilative Crimes Act generally incorporates state criminal laws for crimes committed on federal property, it would be up to federal prosecutors to decide whether to bring charges for any state-law crimes committed on that property.

One major obstacle to the Biden administration’s potential efforts to protect access to abortion would be the Hyde Amendment, which generally blocks the use of federal funds to pay for an abortion in most circumstances. Biden’s latest budget proposal excluded the amendment, but it has not yet been repealed by Congress. That barrier may not be insurmountable, though. The leasing proposal, the three professors argued, “would not be governed by these rules because the abortion provider would be paying the federal government, not the other way around.”

Whether the Supreme Court will allow any of this is unknown, but anti-abortion activists never let that question stand in their way. They have shown themselves to be remarkably creative when it comes to curtailing the procedure at the state level: Texas Senate Bill 8, which set up that state’s bounty scheme to target those who aid and abet abortion providers, was built entirely around exploiting a theretofore unknown gap in federal civil rights laws—and it worked. If the Biden administration is as committed to protecting abortion access as anti-abortion groups are to limiting it, then the White House may have to get as clever and bold as its adversaries are.