“I want to play, but I have to send an email,” my preschooler announced, tapping urgently on his toy laptop. Something wrenched and snapped inside me, just like that. I thought of all the times I had shushed him, telling him we could play right after I finished this email or taped this interview, and I wondered: Was this how he saw me? Was this what he’d remember from his childhood?

Being a working mother is an exercise in balancing irreconcilable tensions. It keeps me up at night with a soul-deep certainty that I am missing too much. When I have childcare, I worry that I’m missing my son’s only childhood. When he’s at home for long stretches, usually because of the pandemic, I worry that I’ll never feel creatively or professionally fulfilled again. I am constantly torn between two opposing and painfully urgent truths: I want to be present for the moments and milestones that make up my son’s childhood, the tiny everyday miracles of becoming a person; yet forgoing the work I love to be a full-time mom makes me feel like my soul, who I am as a person, is slowly atrophying.

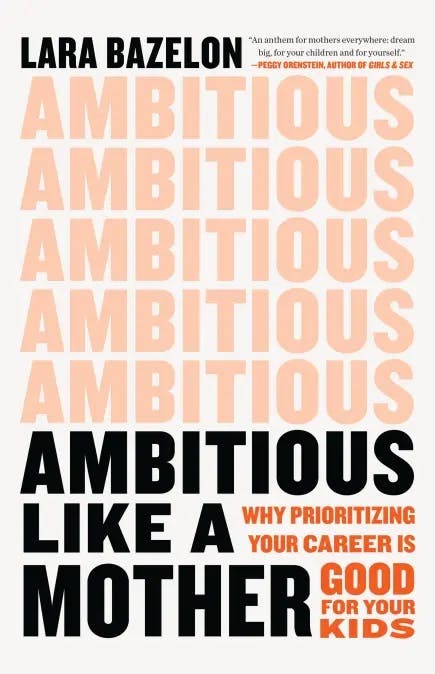

A new book by Lara Bazelon, Ambitious Like a Mother: Why Prioritizing Your Career Is Good for Your Kids, flips the script. What if these decisions aren’t so binary—what if I’m not choosing every moment between being a caring parent or a brazen careerist? What if I’m actually a better mom because of my decision to work?

Bazelon’s thesis is deceptively simple: Happier mothers are better mothers, and our children benefit both from our sense of fulfillment and from seeing powerful women changing the world, even in the smallest ways. Bazelon discards the idea of balancing work and life, as though they could be neatly disentangled, and makes the compelling argument that “work and parenting are compatible, not antagonistic.”

For most people, work is a practical, not a philosophical, issue—an imperative rather than a choice. But regardless of the extent to which work feels like a decision, some of us still feel bad about it, wondering if working motherhood has simply opened whole new ways for feeling like a failure. It is impossible for us to do it all, or to do it all well. Our feelings on the matter are undoubtedly influenced by dramatic social differences in how working parents are viewed. Three-quarters of Americans think it’s ideal for the fathers of young children to work outside the home full-time, while only 33 percent think the same of mothers with young kids, according a 2019 survey from Pew Research. One-quarter of the American public still believes a working mother cannot have as good a relationship with her children as a stay-at-home mom does with hers.

Bazelon proposes a subtle but radical reframing, attempting to “redefine what it means to be a good mother” and in so doing shifting this area of feminism forward. She doesn’t offer practical advice on how to balance what sociologist Arlie Russell Hochschild called “the second shift” in her revolutionary 1989 book by the same name. Instead, Ambitious Like a Mother is a fiery defense of the centrality and importance of women working.

Studies and interviews with grown children of ambitious women, she reports, show that families tend to understand that a woman valuing and prioritizing career doesn’t detract from her love for them—just the same as with working fathers. In fact, working women can influence the course of their children’s lives for the better. The daughters of working mothers are more likely to work as adults themselves—and they’re more likely to have leadership positions, to work longer hours, and to earn more money, according to a 2018 study. There appears to be no link between working mothers and sons’ employment situations, the researchers found—but the sons of working moms are more likely to take on caregiving duties in the home. While working mothers spend less quantitative time with their kids, the quality of their interactions is greater, research shows.

I have been a working mother for most of my son’s life, but I have struggled against deeply ingrained notions of what a good mother does. The ideal mom doesn’t just stay home with her kids, she thrives on it; she finds purpose and fulfillment in childcare and education. I want to be that kind of person, but I am not. In general, I find childcare painfully monotonous. I can handle it for a few days, but after that, I am desperate for adult interaction, for intellectual stimulation, for the thrill of a job done once and well, rather than the unending cycle of diaper changes and mealtimes and imaginative play. Caregiving is a vital profession, a hard-earned skill, a job that deserves much more recognition than it receives. I wouldn’t expect everyone to be good at journalism; why would I have the blind hubris to expect myself to take naturally to full-time childcare?

Instead, as Bazelon argues, I work so that I am a better mom. When I have time to pursue the things that make me tick, I can be more present when I’m with family. When I’m happy, I can more easily share in my son’s happiness, his bounteous joy, because I feel it too. This is the person I would rather reveal to my son; this is the mother I want him to have, even if it means we focus on quality, not quantity, in our time together.

/ In honor of Earth Day, TNR’s climate coverage is free to registered users until April 29. Start reading now.

Whether her own children will understand the primacy of their mother’s career, the jury is still out, says Bazelon, ever the lawyer. She is unsparing in recounting the times she has put work first, including the time she scheduled a trial that conflicted with her daughter’s birthday. Despite her daughter’s tears and her ex-husband’s stony disappointment, she pressed on with the trial because it was important to her and had the potential to change her client’s life. Bazelon frequently discusses how meaningful her work is and how that helps justify her priorities, but she also talks with other parents who find pleasure in running a team, excelling in their chosen field, having financial security, and finding an outlet for their aspirations. To hold importance, work need not change the world—only our experience of it.

Ambitious Like a Mother draws on research and interviews centering Bazelon’s own struggles and successes—a personal frame that intimately highlights the tensions of professional ambition and personal relationships, but one that necessarily puts more wide-ranging viewpoints at the periphery. Although she interviews dozens of women (and some of their children) across diverse backgrounds, there’s little mention of the racial inequities at play in workplaces, both historic and modern. Unlike the women of her mother’s generation, Bazelon writes, “twenty-first-century women are encouraged and often financially compelled to have professional careers.” Yet even in her mother’s generation, it was common for women of color to work outside the home. There were surprisingly traditional elements to the book, with an entire chapter on balancing work ambitions with finding a partner and getting married before giving birth to biological children—priorities for some, but certainly not all, of us.

Perhaps unsurprisingly for the book’s thesis, there is a strong focus on the benefits of paid, professional work. For a dissenting viewpoint, she looks to Lillian, a homeschooling mom of three, whom she sees as “open challenge to my thesis.” The two met when they both appeared on a television show about working moms and Lillian recounted how she and her kids spend their days learning three languages and two types of musical instruments. “I feel like it’s the best job in the world,” Lillian said of homemaking and homeschooling. Yet in fact, I think Lillian’s example supports Bazelon’s argument that parents need to find happiness and fulfillment in their work in order to be good parents. Lillian’s childcare and education work just happens to occur outside of the formal capitalistic system (and inside a highly traditional and patriarchal marriage, by her account), but it is nonetheless work—and some parents feel great ambition for it. A broader view of women’s ambition necessarily includes all type of work, paid and unpaid, all of which is valuable. The problems start when we define women’s ambition too narrowly in one direction or the other, toward or away from the domestic sphere.

Yet Bazelon’s main argument about the importance of ambition and accomplishment is a vital and timely call to action as more mothers join the workforce—and face increasingly greater challenges, particularly in the wake of the deeply disruptive pandemic. Bazelon mentions several times the importance of changing local, state, and federal policies to “make workplaces and home lives more equitable,” including by ensuring paid maternity leave—I would expand this to include all types of family leave, including elder leave and all parental leave—and subsidized childcare and universal preschool. It’s not enough simply to say women should be proud professionals without offering the support and services they need, especially parents with lower incomes, for whom the expense of childcare can significantly limit professional opportunities.

Ambition changes, and balance—or, as Bazelon might call it, stability—is a constant exercise in adjustment throughout one’s life. “Ambition is like water—it has different temperatures, pressure levels, and pathways as it navigates around the solid objects that are spouses, family, friends, children,” she writes. It’s a refreshing view of the role that happiness and fulfillment play in being a good mother and person, and it made me think in new ways about ambition of all types, not just professional—artistic, personal, marital. I was, paradoxically, left examining my relationship to work, thinking about what I put into it and what I get out of it, and wondering what activities outside of my career might bring me (and my son) similar fulfillment. Yet I’m left with a greater conviction that the work I do is important simply because I feel the call to do it. As one woman who wrote to Bazelon said, “The world we want for our kids has to be built, brick-by-brick.… In my book, that means you’re always choosing them.”

The day after my son chose his laptop over playing with me, I sheepishly confided in one of the other preschool moms at the playground. She’s the type of mother I wish I could be—she absolutely loves playing with her kids, going on imaginary hunts and zipping down slides, while I sit on the bench during our playdates nodding serenely and surreptitiously checking my phone.

But when I told her about the urgent emails my son needed to attend to, she had a different take. “How wonderful!” she said. “Isn’t that amazing, that he understands how important it is to have your own thing? He’s so lucky to have a mother like you.” And just like that, something wrenched and snapped back into place inside me.