Like many observers of Russia, I spent part of March 18 watching footage of President Vladimir Putin’s rally at Luzhniki Stadium in Moscow. There was a lot to take in: the call for Russian unity, the banners promising “a world without Nazism,” the Russian flags, and the now-ubiquitous letter Z, which has become a symbol of support for Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. There was also the crowd—the tens of thousands of smiling young people swaying to patriotic songs.

Was the enthusiasm real? That’s what we all wanted to know. The Russian media played up the crowd’s excitement. But some Western journalists were not so sure. The BBC and other news outlets reported that Russians had been forced by their schools or employers to attend the rally, and it seemed, based on interviews outside the stadium, that some people couldn’t wait to leave. A few people took off right after getting their tickets punched.

Meanwhile, something unexpected was happening on YouTube. The Federation Council of Russia’s Parliament ran a livestream of the rally—and the person who set it up did not disable the comment feed. People began to express themselves, many using pseudonyms. They wrote about Putin, the war, and the future of Russia. Some were supportive. But many more were critical. In all, some 11,000 comments were posted.

The recording of the livestream with the comment feed stayed up on YouTube for more than 24 hours before being removed. Some people took screenshots. A Russian activist living temporarily abroad managed to export 4,892 comments into a Google Doc, which he named “Vox Populi-Vox Dei, People’s Comments on the Video.” He sorted these comments according to the number of “likes” and shared the document on social media.

A colleague in Russia shared the document and screenshots with me. As a historian of the Soviet Union, I understood the potential significance of these materials immediately. In a time of extreme state censorship and mass repression, public opinion polls are useless, and unofficial sources are a rarity. Could an analysis of this comment feed tell us something useful about Putin’s wartime Russia?

The document is a fascinating read. Almost all of the comments were written in Russian; a few were in Ukrainian or in English. There were thousands of emojis, including Ukrainian and Russian flags. Words of support for Putin and Russia were interspersed with comments harshly criticizing the war. A number of the comments were from self-identified Ukrainians, some in Ukraine and some in Russia. Many comments spoke of the “unreality of the moment.”

The comments expressing the strongest criticism focused on three key themes. (While the Google Doc with full names is publicly available on the internet, I decided to use initials instead.)

Comments about the spectacle

Many people criticized the rally while watching it in real time. A number of people spoke of the hypocrisy of holding a celebration in the middle of a war, while Russian soldiers and Ukrainians were dying. Some commented on the spectacle itself and compared Putin with other demagogues, such as Hitler.

- “Hypocrites, everyone who participated in this hellish performance, from artists to every state employee, who, for an extra day off and a free hot dog, turn away from the fact that there is a war going on and we are the aggressors in it.”—sassynails S.

- “The tsar probably believes that all people have gathered there of their own free will and sincerely rejoice, but this is an illusion, it’s worth saying that many were driven there under the threat of dismissal and deprivation of bonuses.… He is already not right in the head and his circle only indulges him, organizing this kind of circus of pseudo-supporters of his actions. It’s vile.”—A.R.

- “It was like that in the 30s of the 20th-century in Germany. They yelled, they were happy, [they] greeted their Führer exactly like that, well, one to one. What a horror. Is it really the end?”—D.A.

- “This is the apogee of shame and madness. Someday this video will be shown in history lessons as an example of mass insanity. I live in Russia, but SUCH a Russia I don’t want anything to do with.”—M.O.

Comments about the war

It is illegal in Russia to talk about a war against Ukraine, to refer to the invasion as anything other than a “special military operation.” The majority of comments openly discussed the war, and many described it as a brutal war of aggression. There were numerous calls for justice, with people invoking Nuremberg and the International Criminal Court.

- “People WAKE UP, PLEASE! Those who remain human in their hearts, please realize WHAT WE ARE DOING!!! No war! Peace to Ukraine! Freedom to Russia and Belarus! Putin to The Hague! Nuremberg for everyone involved in this dirty war. I’m ashamed to live in the same country with those who support this lawlessness.”—L.P.

- “Stop Putin! Do not be silent! Spread information about the war in Ukraine. To all of us: do what you must, I will add: do all you can.”—M.F.

- “13,000 dead Russian soldiers died in this war, not [special] operation!!!”—S. R.

- “PEACE TO THE WORLD! Now even this Soviet slogan of a sane person is prohibited, hello dystopia. NO WAR!”—A.V.

Comments about the comment feed

Finally, some of the most popular comments, those with the most “likes,” were expressions of joy and relief at having found like-minded people on a YouTube comment feed. People marveled at the fact that the comment feed was running and that they were able to freely express their views. As people responded to one another, a dialogue emerged between like-minded Russians and Ukrainians.

- “In the comments, as I see it, is the biggest protest in recent years. At least somewhere people can say something, before they turn the comments off.”—Y. S.

- “What’s going on? They forgot to turn off the comments?! Thinking, smart people, I’m proud of you! ❤️”— PRO EGO

- “I am so glad to see so many sensible people in the comments. Recently, I had already begun to lose hope and think that the overwhelming majority supports all this.… But now I look at the huge number of cool comments and I believe that there is hope and we will have a future that we will build ourselves and in which there will be no place for someone like Putin.”—P. S.

- “Beloved, dear, thinking, feeling [people who are] aware of what is happening! Thank you for being, for I had already lost faith, I thought Russia had become a country of slaves, but it’s not! You exist and you also suffer, even if not like we in Ukraine, but it hurts you too and you yourselves don’t know what awaits you. I don’t want to hate you, I wish you well, as well as us, despite the horror that is happening!!! I believe that the old tyrant sick with greed will fall and we will remain free and you will be Finally Liberated yourselves!!! Glory to Ukraine! And glory to those of you Russians who are free in your souls from the power of a tyrant!”—T. D.

So what might the YouTube comment feed tell us about Putin’s Russia?

First of all, we need to acknowledge that this kind of unofficial source will always leave questions unanswered. The people who left comments did so through their YouTube accounts, and many did so anonymously. While this may have been what empowered them to speak freely, it also means that we cannot verify their identities or even where they live.

To work with a source like this means to accept uncertainty and to leave our conclusions open. But relying exclusively on official sources in a closed society has even greater risks.

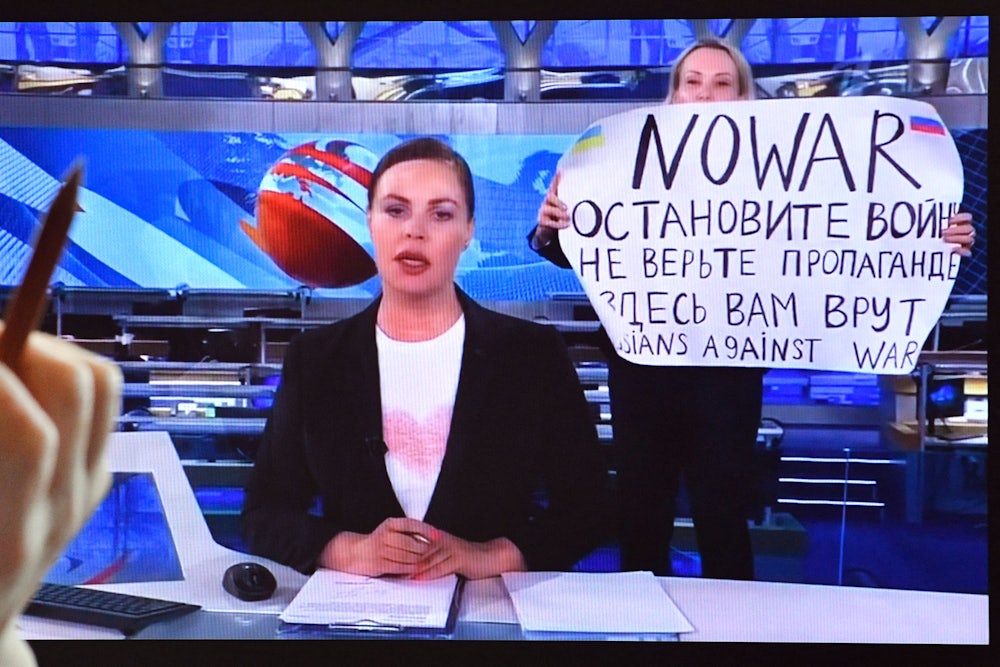

Putin has introduced extreme measures to control the narrative about the invasion of Ukraine. On March 4, the Russian State Duma passed legislation threatening fines and 15-year prison sentences for participating in anti-war demonstrations, expressing opposition to Russia’s military campaign, or even calling it a “war.” Arrests across Russia and criminal cases have followed. The remnants of Russia’s independent media, already under pressure, have almost completely shut down. The radio station Echo of Moscow and the television channel TV Rain suspended operations in early March. Novaya Gazeta, one of Russia’s last independent newspapers, closed its doors on Monday after warnings from the state censor.

Given all this, a source like the YouTube comment feed may be our best shot at examining dissent in wartime Russia.

While we can’t know for certain who wrote the comments on the livestream, we do know that it was viewed by tens of thousands of Russian YouTube users. We also know that it was shared and discussed on social media platforms. Some Russians who posted about the livestream on Facebook and Twitter took solace from the fact that the most passionate anti-war comments received hundreds of “likes.” The Russian colleague who shared the Google Doc and the screenshots with me saw them as important evidence that “not all Russians are bloodthirsty monsters.”

What then might we surmise from the YouTube livestream? It is likely that those in Russia who watched the rally on YouTube and interacted with the comment feed are part of a younger demographic than those who rely on state television for news. They are more likely to engage on social media and to seek out independent sources of information. They are also more likely to oppose the war.

It is highly doubtful that these Russians will rise up in an insurrection. The stakes are just too high in a society where even criticizing the war on social media could be prosecuted as a criminal act. Some are trying to leave Russia. Those who stay will continue to use virtual spaces to find each other. We should continue to look for these conversations to have a better sense of what may be happening behind the scenes.

When I watched the rally, my mind turned to the diaries of Victor Klemperer, a German-Jewish scholar who observed Hitler’s rise to power. In a diary entry from November 1933, during Hitler’s first year as chancellor but before he declared himself Führer, Klemperer described how the “boundless” propaganda and parades created a sense of inevitability, a belief “in the power and permanency of Hitler.”

Putin wants to create a sense of inevitability about his rule and a singular narrative about Russia’s “mission” in Ukraine. Online platforms can provide a means for people to challenge this narrative and express dissent, a place for resistance to grow. They can help Russians who oppose Putin’s brutal war of aggression to know that they are not alone. Russian activists living abroad recognize this, and will likely continue their efforts to transmit accurate information about the war into Russia and support dissent via the internet.

With the banning of Facebook, Instagram, and other social media platforms, dissent may also find its allies in unlikely places. Someone at the Federation Council left the YouTube comment feed on, after all. And it was left up for more than a day. Was this an intentional act or simply carelessness? We may never know.

Finally, is it possible that the YouTube comment feed was part of a concerted effort on behalf of a particular organization in Russia or Ukraine, an “astroturfing” effort? Could Russia’s Federal Security Service or Ukraine’s Foreign Intelligence Service somehow be behind this? The wide range of responses makes this feel highly unlikely, and one would imagine that intelligence agencies have more important things to do at the moment. But anything seems possible in the current environment—which is another reason to leave our conclusions open. Should this turn out to be the case, it will make an even better story.