Randolph Bourne, the brilliant young New Republic writer who died in 1918, is now best known for his bold claim: “War is the health of the state.” It’s an unnerving thing to contemplate, and it’s not hard to imagine the dizzying extremes that have been realized in the decades that followed his death. They couldn’t have been far from the mind of President Dwight Eisenhower when he warned of the “military industrial complex” and its ambitions, which—as Rosa Brooks chronicled in her 2016 book, How Everything Became War, and War Became Everything—have all but devoured the state. But is it impossible for these dire visions to be transformed or repurposed into some more hopeful, productive end? It may indeed be the case for “the moral equivalent of war,” the nonmilitary form of war once envisioned by William James in a 1906 essay.

It’s all the more worth contemplating today, because in the case of Ukraine, the United States is engaged in the biggest war of our time, and war’s “moral equivalent” is precisely what the U.S. is waging. The military, far from being “everything,” has had little to no role in it at all. This version of warfare is helping to pull the country together, as James hoped it could, even without an army in the field. Here is the lesson: If the military is not everything, or even nothing much at all in the most critical war of our time, then for our own security we should commit to building up even more of the moral and psychological weapons for conducting it.

William James was not proposing to do away with war. As he admitted, “So far, war has been the only force that can discipline a whole community, and until an equivalent discipline is organized, war must have its way.” What he meant by that was that war was—regrettably—still the best way to instill ideals of honor, or as he put it, the “manly virtues which the military party is so afraid of seeing disappear in times of peace.” These words were somewhat prophetic: Since the end of the Cold War, an authoritarian right has commandeered the manly virtues that had once been organized in defense of democracy, not just in the U.S. but in Europe as well.

James envisioned a moral equivalent of war like so: “We must make new energies and hardihood continue the manliness to which the military mind so faithfully clings.” What James had in mind was “a conscription of the whole youthful population,” to form a “party of the army enlisted against Nature,” going into coal mines, working freight trains, so his Harvard students could see what it was like. One might say that we now need such youthful conscription for an army on the side of Nature, in favor of it, to limit the carbon that is setting fire to the world. President Jimmy Carter once called for the moral equivalent of war, a term he directly borrowed from James, just for the sake of urging people to use less energy, wear sweaters, and accept higher oil bills. But this was not so much like a “war” as it was a call for the top-down disciplining of the nation; in that way it did not meet the Jamesian test: “We should be owned, as soldiers are by the army.”

James could not have imagined that the moral equivalent of war could be carried out in an actual war, or that there might be an opportunity to conduct war in an intensively globalized world by other than military means. But in the case of Ukraine, the odd combination of a desire to fight for democratic ideals without an army, to take risks but not to shoot, might now have encouraged James to imagine the possibility. Ukraine has, in fact, already been a discipline for the country, or a way of organizing our politics. In particular, it has been a release for the GOP—a chance to go back to being the military party. At some conscious or unconscious level, many of these Ukraine hawks grasp that they are, at last, breaking free from Trump’s “America First” vision. Now they have an alternate means of directing what James called the “manly virtues,” this time not against our own country internally but against a new external actor, and against an invasion that could escalate and become, for us, an existential threat. In our moral equivalent of war, it helps that—so far, we hope—this army of Putin’s Russia is so much crueler and weaker in the field.

To capitalize on this momentum, we should continue to build up the institutional capacity for the moral equivalent of war. The chief way to do so is to create a new kind of alliance to replace NATO, which has done so little to aid in this regard: It is not the unity of NATO but of the European Union itself that is the bigger threat to the security of Russia and the success of its invasion. The U.S., for its own security, should figure out every possible way to engage with the EU, which is, in this case, the real bulwark of our own security, thanks not just to the economic sanctions it can levy but their moral and psychological equivalents. The U.S. should seek every possible means to be part of the shaming that the EU can potently mete out on Putin and his regime; this is much more effective in a globalized, wired-up twenty-first century world than in a shooting war.

The U.S. should also be angling to play a bigger role in global institutions such as trade organizations, and even the International Criminal Court, which can discipline countries like Russia and China for their repudiation of the values of liberal pacific civilization. Even Lindsey Graham is lately cheering on the ICC, even if in the same breath he would oppose it. It seems to be a manly thing to have Putin indicted as a war criminal by the ICC, but not a manly thing for the U.S. to join it. But the more we remain aloof from these institutions, the more we weaken our ability to conduct the moral equivalent of war in circumstances where a real war is not an option.

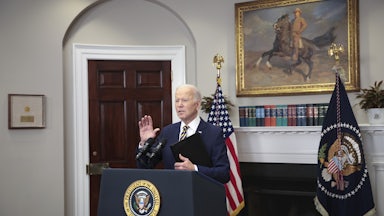

This is not nearly enough, however, to realize James’s hope to have a moral equivalent of war, or to discipline our own country to fight one. The Biden administration is making a mistake by thinking it is just a matter of asking people to pay more to fill up at the local gas station: It must provide a release to the warlike impulses that so many millions in the country are feeling as they watch the emerging atrocity in Ukraine. Someone in the administration should familiarize themselves with Gandhi’s letters and editorials, or pick up Crowds and Power, the great European classic by Elias Canetti. The moral equivalent of war—outside of the military—is a matter of creating crowds and creating networks to fight it. We all—not just the administration, but business, universities, the labor movement, everyone—need to build these crowds, and keep them growing.

As Canetti wrote, “The more fiercely people press together, the more certain they feel that they do not fear each other.” In this way, crowds create a feeling of equality and multiply the force of civic virtue; being a part of something bigger abolishes the distance that people ordinarily keep with each other; it inspires some of the same feelings as being in the army. Crowds can be forged in the fire of crisis—we are witnessing this now as opposition to Putin’s invasion becomes a larger global cause. And since the moral equivalent of war can only be waged on a worldwide basis, we should have a hand in building crowds in all the countries of the world, to protest not just the slaughter of Ukrainian men, women, and children but the hapless teenagers serving in the Russian army, as well.

Likewise, along with bigger crowds, there should be more “packs,” to use the Canetti phrase, referring to the ancient human instinct to form into small groups that are in the hunt together, and have a military character. Here, too, in the U.S., we should have what is already happening in Europe—volunteer networks, encouraged and sponsored by society. These networks are facilitating the resettlement of refugees; and providing emotional, medical, and psychological care; and even going into Ukraine to provide it. Wherever the martial virtues are on display, people tend to do more, and find ways to care for one another. We need to keep these tendencies, the possibilities they create, and the pragmatism of William James alive, now more than ever, for we are finally in the early stages of learning how to actually fight the good war. This truly is a war that can become everything; one that never needs to end.