In the fall of 1962, William F. Buckley Jr. befriended a convicted killer. Seven years earlier, Buckley had founded National Review. He and its editors—an idiosyncratic coterie of hypergraphic libertarians, ex-Communists, and Christian traditionalists—had succeeded in reinvesting the hoary, quietist, vaguely continental term “conservative” with American vim, vigor, and revolutionary flair. But Buckley, a few years shy of his run for mayor of New York City and the debut of his television program Firing Line, was not yet a household name. And National Review, its pages filled with stylish reactionary chatter well to the right of the Republican mainstream, remained a relatively parochial concern.

And so Buckley was bemused to discover—via a brief column, flagged by an NR underling, in the Ridgewood, New Jersey, Herald-News—that his little magazine had found a reader inside the Trenton State Prison death house: a 28-year-old autodidact by the name of Edgar “Eddie” Smith, sentenced to the electric chair in 1957 for the murder of a teenage girl named Victoria Ann Zielinski. Smith described himself as an “ardent Barry Goldwater fan” and mentioned that his source of NR issues—a Roman Catholic prison chaplain—had relocated to another facility. Buckley, ever curious and impishly attracted to the incongruous and odd, wrote a letter to Smith offering a “lifetime” subscription to NR.

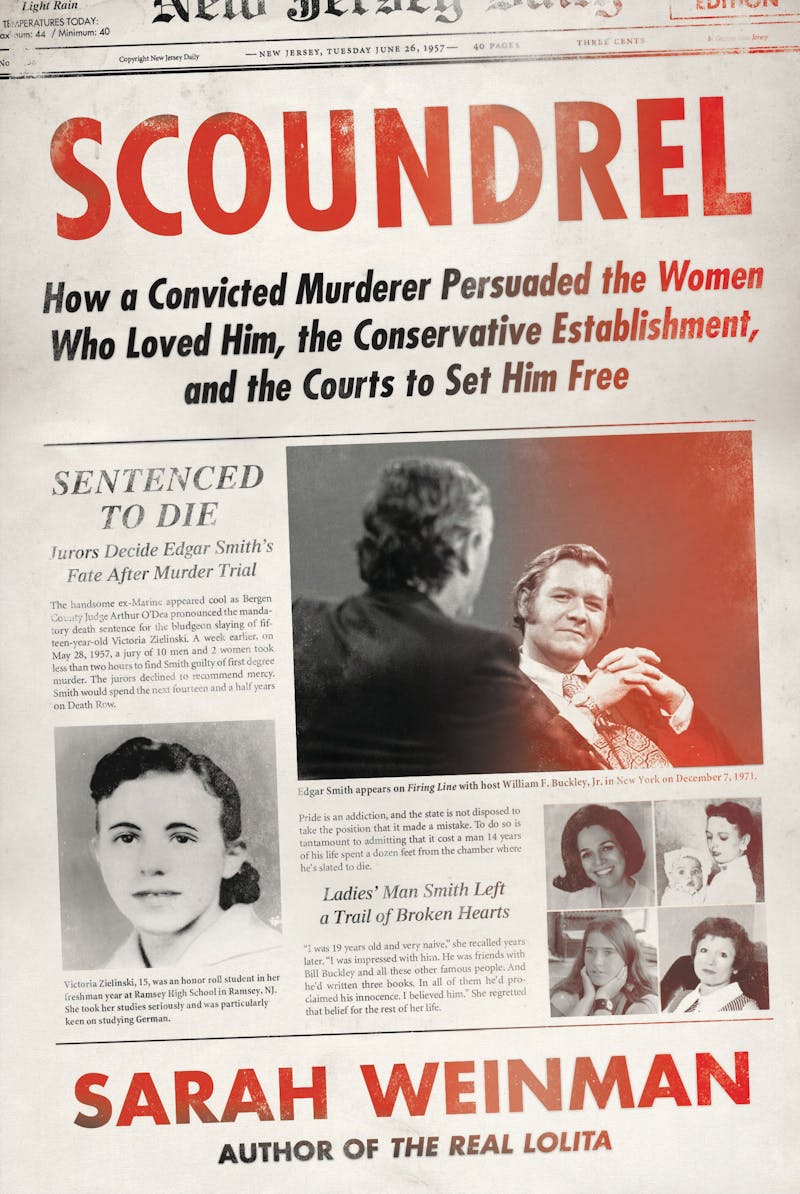

The tragic and gripping saga that ensued is the subject of Sarah Weinman’s new book, Scoundrel: How a Convicted Murderer Persuaded the Women Who Loved Him, the Conservative Establishment, and the Courts to Set Him Free. As in her previous book, The Real Lolita, Weinman tells this lurid tale with all the narrative texture and tempo—and only some of the tawdriness—of a true-crime genre classic. Relying on original reporting, court documents, and thousands of pages of letters exchanged between Smith, Buckley, and an editor named Sophie Wilkins, Scoundrel is an agonizingly intimate depiction of an unlikely epistolary love triangle—the bloody consequences of which would haunt its besotted principals for decades to come.

In Weinman’s telling, Buckley’s peculiar dedication to Smith had little to do with his politics: Buckley was and remained a champion of police, prisons, and the death penalty. It was instead Buckley’s character—his credulity, loyalty, and self-regard—that allowed Smith to ensnare him. In this way, Scoundrel is a bit like Janet Malcolm’s The Journalist and the Murderer in reverse: with Smith in the position of the journalist (the “confidence man, preying on people’s vanity … and betraying them without remorse”) and Buckley in the position of the journalistic subject, who is made a fool.

With Buckley, however, the apparent contradiction is the point. If the Edgar Smith case suggests anything about Buckley’s brand of politics, it is precisely his comfort with self-serving paradox—with incoherence, mutability, and ironclad rules that apply everywhere except for where they don’t. “Conservatism,” as the composer Frank Wilhoit once put it, “consists of exactly one proposition, to wit: There must be in-groups whom the law protects but does not bind, alongside out-groups whom the law binds but does not protect.” It was Edgar Smith’s extraordinary fortune to find himself warmly invited—by Buckley himself—into the former category.

In 1962, Buckley had not the slightest premonition of the treacherous romance ahead. He was merely intrigued by the learned, blue-collar convict and his apparent composure in the face of extinction. Buckley assigned a young NR staffer named Donald Coxe to investigate Smith’s case. Over the course of several years of correspondence—Smith’s appointment with oblivion (and thus the expiration of his National Review subscription) was delayed by repeated judicial stays—Buckley was seduced, becoming convinced, first, of his pen pal’s legal acumen, then of his literary talent, and, eventually, of his innocence.

The letters between the two men were variously philosophical, political, and quotidian. Buckley often encouraged Smith to pray. (December 1962: “I hope … that during this season especially you will be comforted by a close relationship with God.”) Smith chided Buckley for his sesquipedalia: “Only a guy with a secretary to do all the work would use a word like THAT!” (The word was imperturbability.) Gradually, ease and affection seeped into their cordial but guarded discourse. It was in the course of a tortured exchange over Smith’s alleged crime—“My God,” wrote Buckley, “I wish I could be absolutely certain you hadn’t [written as haven’t in the letter, then struck through] killed that girl”—that Edgar first referred to Buckley as “my friend.” Smith replied that he wished Buckley “could be absolutely certain,” too, but would settle for his reasonable doubt. Then, explaining the stoicism Buckley had so frequently admired, Smith wrote, “I assure you, my friend, if I thought soap-box oratory would serve me any good purpose, I would climb onto the closest box handy, and put George Wallace to shame … [but] my situation is not going to be improved by breast-beating and lamentations, however loud or sustained....”

Smith’s tone was self-conscious and ingratiating—at times, obsequious. His writing, which Buckley once called “Victorian to the point of prudery,” is full of name-dropping, chatty interior clauses, and wry little jokes; more than anything, it resembles the prose of William F. Buckley Jr. Whether Buckley ever noticed his protégé was writing to him in what amounted to a low-rent impression of his own style, the record does not show. (Weinman includes an apt epigraph from Dostoyevsky’s Raskolnikov, but Smith more frequently reminded me of Patricia Highsmith’s Tom Ripley; before 1962, Smith was known as “Eddie Smith,” but by 1970, he began to use the byline “Edgar Smith Jr.”) Buckley, alas, was a man acutely susceptible to flattery. He coveted the esteem of those he admired and relished the loathing of those he did not. He was notoriously generous and loyal to his friends and, as Garry Wills once put it, “too trusting of people he liked.” Eddie Smith, meanwhile, was a consummate charmer, equal to the task of beguiling one of history’s great beguilers. He praised Buckley and mocked his liberal rivals in the same breath. As he wrote to Buckley early in their courtship, “I am very much thankful for the fact that since I have been in contact with National Review I have been quite fortunate to become acquainted with some very nice people. I wonder if New Republic would have been as good to, or for, me.”

Though the prosecution’s case against Smith was somewhat slipshod—Part 1 of Scoundrel covers the crime and trial in detail—there was strong evidence against him: He drove Vickie Zielinski the night of her murder; he tried to hide a bloodstained pair of trousers; and he made several incriminating statements after his arrest (“that’s when it hit me really hard I must have been the one who really did it”)—a confession Smith would later claim was coerced. It wasn’t only flattery and Smith’s legal cunning, however, that won Buckley to his side. As Coxe told Weinman, “We were taken in, I suspect, in part by our unwillingness to believe that anyone who loved NR could be a savage killer.” (One wonders whether Coxe would explain National Review’s fondness for Augusto Pinochet the same way.)

Weinman notes the irony of Buckley going “against his own conservative ideology” to champion Smith’s cause, but she misses the shrewd way in which Buckley used Smith to bolster his own priors. For one, Buckley refused to view Smith’s plight as indicative of a larger social problem; just the opposite. Throughout the ’60s, Buckley remained an advocate of capital punishment and won support from the NYPD during his 1965 mayoral campaign by fiercely opposing a civilian review board. Indeed, when Smith wrote to Buckley suggesting that police brutality might undermine law and order, Buckley replied with rare derision: “For the very first time, I must own I found your comments a wee bit platitudinous.” He went on, “What you don’t have anything to say about is the dilemma of our time, namely, what to do about the evanescing rights of people not to get killed, not to get raped, not to get robbed.”

Meanwhile, in his columns, Buckley frequently cited Smith, his “friend” residing “in the Death House at Trenton,” as an authority on matters of prison and crime—adding a streetwise air to otherwise aloof, academic speculations. (In a piece on Chappaquiddick, Buckley quotes Smith: “Seriously, Bill, I told a better story than Teddy, and I got convicted.”) Buckley’s advocacy on Smith’s behalf, meanwhile, served as a talisman to protect against the charge that his frequent calls for more punitive policing and jailing were overzealous, indiscriminate, or mean-spirited. “The notion that conservatives are less interested in justice,” he told one reporter, “is highly self-serving and highly untrue.” Many conservatives, he said, would like to see “much more justice than in fact we have”— by which he meant more incarceration. “[W]hat we have now is something like 15 percent of malefactors actually ending up in prison. I’d like that figure to be 100 percent,” but, he added, alluding to Smith, “I’m certainly not disposed to put innocent men in jail, let alone execute them.”

In 1965, Buckley visited Smith in person and wrote a feature-length profile for Esquire detailing their unlikely friendship, quoting from Smith’s erudite letters, and making the legal case for a retrial. Buckley used the fee for the article to seed a defense fund and connected Smith with powerful lawyers in Washington. (Buckley would remain Smith’s financial proxy until his release from prison.) The Esquire piece brought Smith some celebrity—not least among literary elites—and he began to take his own writing more seriously. “What I have in mind is an historical account of events, interlaced with my personal impressions and observations,” Smith wrote to Buckley in January 1967. The following year, Buckley connected Smith with Sophie Wilkins, a “loud and passionate,” Vienna-born editor at Alfred A. Knopf with thwarted literary ambitions of her own. Wilkins was desperate to shepherd a bestseller into the world. Buckley cemented their fateful alliance over lunch at Paone’s, a regular haunt near the NR office, charming her in his (nearly) inimitable style. As Weinman writes, “His smile was brilliant, his manner genial. At one point, Sophie quipped, ‘Ah well, let’s not be juvenile.’ To which Buckley replied, ‘Ah, let’s!’” After that, “All her reservations about him dissipated immediately.”

Wilkins needed no convincing, however, to believe in Edgar Smith, whose prose she had so admired in the pages of Esquire. To make an author out of the well-spoken convict struck her as “a once in a lifetime opportunity.” She began writing to Smith regularly. And with startling speed, the seductive subtext of Buckley and Smith’s dalliance was literalized in the union of Edgar and Sophie. Within months, they developed a mutual sexual fascination, exchanging lengthy pornographic fantasies between drafts of Edgar’s book. He called her “Red;” she called him “Ilya.” Smith referred to their carnal flights of fancy—smuggled in and out by his lawyers to evade the prison censors—as “hatkic epics,” an acronym Wilkins devised for “have to keep it clean.” Buckley cottoned on to this salacious development in their editor-writer relationship; he didn’t discourage it. From then on, writes Weinman, “Edgar was their shared experience, one that, like survivors of a war, only the two of them could fully share.”

Edgar Smith’s book, Brief Against Death—which, in addition to its literary aims, Smith told Wilkins, was intended to put “evidence that will be inadmissible in court” before the eyes of potential jurors—was released to near-universal fanfare in 1968. (“For such a review as you got in the New York Times,” wrote Buckley to Smith, “I would go to the chair.”) But not before Wilkins, in the course of routine editorial disagreements, was confronted with Edgar’s rage. After a particularly acrimonious visit in Trenton, Smith wrote to her, “this was the first time I’ve ever found you tiresome. When horses get like that, they are shot and sent to the glue factory.” After a bewilderingly callous letter from Smith, Wilkins wrote to one of Smith’s lawyers, “It is not the first time I have received a vicious slap from this strange man, to whom, and to whose cause, I may well have given myself somewhat too unreservedly.” “Frankly,” she wrote in another letter, “is our friend psycho?” And, perhaps most perceptively, in a breakup letter to Smith—one of several—she wrote, “If you could gain an insight into what it is that causes you, inevitably I am afraid, to hurt yourself by means of hurting those who love you, and serve you, it might all be wonderfully worth while.”

Amid this turbulence, Buckley often played couples counselor, affirming Wilkins’s hurt and coaxing Smith to do the same; at one point, Buckley chastised Smith for his “cruel and unusual punishment” of “someone who all but broke her back” to get his book published. (Buckley’s letters to Smith are scattered with penal language; morbid humor or Freudian slip? Difficult to say.) Meanwhile, Smith’s celebrity grew. In 1970, he published a novel—to similar acclaim—and began receiving letters and visits from other female admirers. (“Did you know that I so bedazzled the ladies?” he wrote to Buckley. “I guess I am just a big, bad wolf.”) In a more pensive mood, Smith summarized the last year of the 1960s thus: “too much work, too little food ... and the usual—the total inability to understand women.”

Good news, however, came in 1971, when a circuit court judge threw out Smith’s confession—retroactively applying the precedent in 1966’s Miranda v. Arizona. (Smith had not been apprised of his right to remain silent, among other violations, in 1957.) He was awarded a new trial, and his lawyers convinced him to plead guilty to second-degree murder. He was credited with 14 years’ time served, and the judge suspended the remainder of his 25-year sentence on account of his “impressive” rehabilitation. Edgar Smith, then the longest-serving death row inmate in U.S. history, was free. “Immediately after the guilty plea and the final ruling,” Weinman writes, “Smith climbed into a limousine, Buckley took the seat next to him, and they went straight to the television studio to record two riveting hours of Firing Line, which aired on consecutive weeks.” On the way, they ate roast beef sandwiches and drank rosé wine.

If only the story ended there—with a taste of freedom, greasy deli-counter meat, and wine from paper cups. Smith enjoyed his celebrity for a few years, wrote two more books, remarried, and moved out West. Buckley rarely heard from his friend, except when Smith wrote to ask for money or apologize for failing to pay it back. Sophie Wilkins turned to other projects. As Buckley reflected later, Smith had “walked out of Trenton into the more incapacitating bonds of anomie. He became, slowly, bored—and then boring.” Buckley saw his friend once more in San Diego, in March 1975, where Smith made a show of paying for the drinks despite owing Buckley thousands of dollars.

A few months later, Smith, driving his wife’s car, abducted 33-year-old Lisa Ozbun from a parking lot in Chula Vista and plunged a knife into her stomach, piercing her liver and diaphragm. She barely escaped with her life. Smith went on the run. Two weeks later, he called Buckley’s secretary, leaving the Las Vegas address where he was staying. Buckley got the message and notified the FBI. Smith was caught, tried, and imprisoned for life.

“What has come of it all?” Buckley wondered in a 1979 Life magazine reflection on the saga. His answer: nothing. “No solutions to the human predicament suggest themselves from the experience.” Later he added, “It is a pity that nothing that is generally useful has been written as a result” of the Smith tragedy. With the publication of Weinman’s gripping book, and the enormous feat of archival sifting and synthesis she achieved to produce it, we can say that’s no longer true. But I find her conclusions somewhat wanting. Weinman writes that Smith’s “wrongful exoneration and the accompanying adulation obscured the damage inflicted upon so many women”—Zielinski and Ozbun, of course, but also Smith’s wives, his doting mother, and his daughter and granddaughter (with whom, later in life, he exchanged menacing letters). Echoing the insights of the #MeToo movement, Weinman writes, “Edgar Smith’s horrible acts, like so many other horrible acts of atrocious men then and now, were overlooked, explained away, or ignored because of his talent—and because women are expendable.”

Surely there is some truth in this—Smith’s talent was an alibi, not merely for himself but for the judge who suspended his sentence and for Buckley and Wilkins, who suspended their doubts to help his cause. Likewise, the extraordinary license and sympathy granted Smith was no doubt a consequence of certain odious social facts—his whiteness, for one, but also an undercurrent of sympathy, among men, for crimes of sexual vengeance. As Smith eventually admitted, he killed Vickie Zielinski after she spurned his advances. Even while protesting his innocence, Smith eroticized his young victim, as if her sexuality itself would exonerate him. In his book, Smith referred to Zielinski as “an exceptionally well-developed fifteen-year-old.” Buckley, in his first piece on the case, called Zielinski “flirtatious,” and, later, a “nubile teenager.” These choices are symptomatic. Violence committed by a man belittled or emasculated by a woman’s disinterest is uniquely legible to the league of men—including upstanding elites, jurists, and writers. Sexual violence exists on a spectrum with their own aggressive impulses, particularly those ignited by rejection, impotence, and shame. And despite considerable progress, the misdeeds of men are still tolerated and forgiven by those who identify with their passions.

But there is also great danger in treating Edgar Smith’s as merely “a story of a wrongful conviction in reverse,” as Weinman puts it. In telling such a story, one would have to take careful pains to avoid vindicating—if not explicitly, then by logical inference—the entire criminal justice system, the impulses of police, prosecutors, judges, and juries, and their capacity to distinguish the guilty from the innocent. These are pains that Weinman does not take. Remarkably, it is Buckley who makes some (fleeting) sense of this matter: “Edgar Smith has done enough damage in his lifetime without underwriting the doctrine that the verdict of a court is infallible.” More, not fewer, prisoners—including those convicted of terrible crimes; including those who are guilty—deserve the sort of humane compassion and dedicated attention briefly afforded to Edgar Smith.

As Wilkins’s son told Weinman, the story of the Buckley-Smith-Wilkins relationship “would have made a wonderful novel or a wonderfully trashy one. The three key characters—the celebrity political columnist (rich, Catholic, but culturally upper-class WASP); the brilliant psychopathic jailhouse lawyer, working class, Protestant; and the sparkling bright articulate Jewish woman editor—could hardly have been more different in background and personality, but they came together in a most amazing interaction.” Scoundrel lacks, however, the psychological sophistication of a great novel, dedicating many more of its pages to minute legal machinations—and the gruesome details of Edgar Smith’s crimes—than to textured analyses of character. Psychology is not the book’s remit. Weinman set out to write a crime story, and she has done so.

It is perhaps a matter of taste that I found it so much more compelling as a love story—a story about what love will make people do and abide, and the harms we find ourselves inflicting in its pursuit. After all, the obligation to political and ethical coherence stops at the moment love starts. As Slavoj Zizek has observed, love is evil in this sense, a selfish revolt against our obligations to the world. Love haunts and bedevils our universal frameworks; the rot in the crossbeams of our carefully crafted moral abodes. As Buckley observed when Smith secured his freedom, “A court of law is many things besides a truth-finding mechanism. It is a chamber in which subtle social and institutional conciliations are effected.” If Edgar Smith had any genius, it was for finding the liminal spaces and fugitive moments where the law betrays its susceptibility to the corruptions of love.

Buckley and Wilkins spent many years brooding over their respective roles in the Smith saga—seeking comfort, if not absolution, from each other. Wilkins was capable of admitting, as Buckley could not, that love drew her to Smith. And yet she remained ambivalent about claiming “biochemistry” (as she termed it, in one letter to Buckley) as her alibi. Rather, Wilkins cites a contradictory—and, therefore, believable—stew of erotic, maternal, and acquisitive desires. In a letter to Buckley in 1979, Wilkins reflects, “Did the fact that Smith’s mother appeared in my office, with the promise of a manuscript, just when my second son had gone off to Stanford and I was ripe for an ersatz ‘son’ in my life ... have anything to do with it?” Perhaps, yes. Wilkins concludes her letter to Buckley: “to this obsessive end”—her entangled desire for a son, a lover, and a book—“I used him, I used Knopf, I used you.” (Wilkins spent the happier latter years of her life translating Robert Musil’s modernist masterwork The Man Without Qualities, a novel whose aimless bourgeois characters become infatuated with a murderous carpenter named Moosbrugger. “Something must be done for Moosbrugger,” one laments. “This murderer is musical!”)

Buckley was never inclined toward such self-reflection. He protected himself from the full weight of Smith’s betrayal by cultivating ignorance about his own motivations—a feat of soothing self-deception he would repeat throughout his life. Buckley held grudges against his enemies, but he always forgave himself. As Wills once remembered Buckley, “He reminded me of one of Wodehouse’s blithe young men—Psmith, say, or Piccadilly Jim—who act forever on impulse…. He wrote rapidly because he was quickly bored. His gifts were facility, flash, and charm, not depth or prolonged wrestling with a problem.” (It was for this reason, too—Buckley’s inattentiveness and lack of discipline—that he never produced a great book.)

In the Life piece, Buckley admits his attraction to Smith, but only in the vaguest terms. “A certain aura attaches to any man sent off to be executed,” he writes. And later: “Here was a romantically engaging vision of a young man, occupying a cell eight feet by eight feet, in solitary confinement.…” In a letter to Wilkins, Buckley concludes, blandly, that there was “a permanent coarseness” in Smith “that seemed to reassert itself almost within minutes of his liberation. A great pity.” Buckley found some perverse consolation in 1981, when Norman Mailer’s own incarcerated literary protégé, Jack Henry Abbott, stabbed a man to death just a month after being paroled. Writing to Wilkins about the Abbott affair, Buckley morbidly mused, “At least ours had the decency to wait a few years, and to botch the job.”

It’s not surprising Buckley weathered the Edgar Smith experience with relative equanimity. Buckley’s conservatism was a revolt against structural thinking: against the liberal notion that individuals are shaped by society and circumstance, and that, therefore, hierarchies of class and race and achievement are contingent historical facts, not artifacts of a God-given natural order. It was Smith’s erudition, his elegant prose—more so than any legal reasoning—that convinced Buckley of his worthiness for freedom. Indeed, Buckley had been troubled, at their first meeting, by the incongruity between Smith’s patrician writing style and his vulgar, “faintly coarse” manner of speaking, which betrayed a “background of football lockers and poolrooms and beer taverns….” Tasked with explaining Smith’s unworthiness for freedom, Buckley returned to this indelible “coarseness,” a primitive streak that neither his nor Wilkins’s edifying ministrations were sufficient to contain. Before Smith attacked Lisa Ozbun, Buckley had considered him an exception that proved a rule (that the crude and common men who reside in prisons and jails are there for a good reason). It required no great feat of worldview reordering for Buckley to accept that Smith was unexceptional instead.

In the 1980s, under the presidency of his dear friend Ronald Reagan (who signed his many letters to Buckley “Sincerely, Ron”), Buckley’s long war against big government liberalism flourished. Reagan-era conservatives dismantled Great Society programs, pairing a deliberately threadbare welfare state with punitive policing and sentencing as their preferred solution to the so-called urban crisis. The prison population boomed. In 1985, as The Washington Post reported, the federal government officially abandoned the idea “that prisoners can be rehabilitated.” Now, the official purpose of incarceration was retribution only; the unofficial purpose was to warehouse the nation’s poor. With the demise of the rehabilitation era, the popular notion that America’s prisons might be full of undiscovered geniuses—Lawrences of Leavenworth and Jameses of Joliet—died, too. America’s romance with the literary prisoner was over. No one was eager to meet another Jack Abbott or Eddie Smith. A coarseness reasserted itself in the country. And Bill Buckley was delighted to see it.