During the early days of the pandemic, humorist Fran Lebowitz made a shrewd point about Covid-19. “The upside of being old … is that almost everything that happens reminds you of something else,” she said in an interview. “This is the first big thing that has happened in my adult life that didn’t remind me of something else.”

Now during this winter of our discontent—when it feels as if our lives will be governed for decades by new variants with Greek letters—Lebowitz’s observation has become truer than ever. The pandemic has universally shaped the national mood and dominated our collective psyches like nothing since World War II.

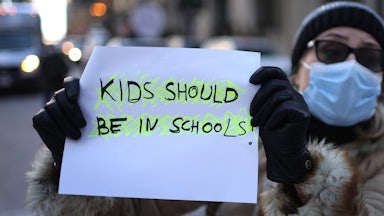

In sharp contrast to everyone else doomscrolling about the pandemic, political handicappers seem determined to treat 2022 as an ordinary election year. As a result, we are awash in glib forecasts about how the inflation rate, Biden’s approval numbers, or the Democratic stalemate on Capitol Hill will determine the congressional elections. But that’s like ignoring the Depression in making political predictions about 1932. So much depends on whether we will be fighting over remote learning and mask mandates this fall. All the experts bloviating on cable TV have no idea whether the pandemic will be raging or waning as Americans vote.

Lee Miringoff, the director of the Marist Poll, decried “the growing tendency to predict elections earlier and earlier, even as the reality of events hits later and later.” He believes that the national mood about Covid in late September and early October will play a major effect in determining voter behavior. “Remember,” he said, “that the pandemic affects almost everything—the economy, health care, education, employment, and family finances.”

If the pandemic becomes endemic (with each variant less severe than the last), it could boost the Democrats’ prospects in 2022 and beyond. I will confess to believing last summer that Biden would get major political credit if Americans continued to revel in “the return to mask-less, Zoom-free, hug-filled lives.” Biden, too, was swept up in this premature euphoria as he declared at the White House in early July, “The virus is on the run, and America is coming back.”

Since then, of course, it has been the Biden White House that has been on the run as the virus keeps coming back.

The return-to-almost-normal fantasies of the summer did not anticipate the gravity of the delta variant and the omnipresence of omicron. The administration’s failure to plan for the current heavy demand for instant test kits and high-quality masks was an unforced error that has not been wiped away by Biden’s lame who-knew-omicron-was-coming explanations. Last week, Kamala Harris offered a gibberish response about the nature of time when asked a simple question about what quality masks Americans should be wearing. And unlike a year ago, when Democrats could blame incoherent guidance on quarantines and masks from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention on the incompetence of the Trump administration, they have no excuse now that the agency is headed by Biden’s beleaguered appointee, Rochelle Walensky.

A strong case can be made that Biden won the 2020 election in large measure because of Donald Trump’s tragically and typically erratic response to the pandemic. As Democratic pollster Zac McCrary told me, “Our brand on Covid was that we were the sober, serious people. But two years into the pandemic, with as much uncertainty as ever, the Democratic brand has been damaged.”

In defense of Biden, no foreign leader—except in authoritarian countries that can impose extreme lockdowns or island nations that can better insulate themselves—has figured out a lasting formula to contain Covid-19. For all its lockdowns and sky-high vaccination rates, Europe too has been devasted by omicron. The World Health Organization, in a chilling prediction, anticipated that half the population of Europe would be stricken with Covid by the end of February. Trying to stress the importance of vaccination, Anthony Fauci also sounded a downbeat note last Wednesday at a White House briefing. “Virtually everybody is going to wind up getting exposed and likely get infected,” he said. “But if you’re vaccinated, and if you’re boosted, the chances of you getting sick are very, very low.”

The polls reflect this pessimism about the pandemic. A new Axios/Ipsos national survey found that 52 percent of Americans believe that a return to something resembling normal is more than a year away. According to overall calculations last week by FiveThirtyEight, “Biden’s approval rating on COVID-19 dropped below his disapproval rating for the first time.” Since mastering the virus had previously been one of Biden’s strongest suits, continued negative numbers on the pandemic would mean that a dismal November was in the cards for the Democrats.

After two years of vicious infighting over the virus and vaccines, it is harder than ever to separate Covid from its political context. Republican strategist David Winston, who has long worked closely with the congressional wing of the party, said, “In too many cases, the country is looking at scientists through a political lens and not a science lens—and that creates significant problems.” Or as pollster Andrew Smith, who directs the University of New Hampshire’s Survey Center, put it, “Covid has become a political issue rather than a public health issue.”

Part of the problem is that victory over the virus has become hard to define—especially since no major scientist believes that it can be eradicated like smallpox. In a speech last Thursday, Biden admitted, “I know we’re all frustrated as we enter this new year.” Stressing the importance of wearing masks, the president reflected reality as he said, “It’s not that comfortable. It’s a pain in the neck.”

But apocalyptic fears that the full-blown pandemic will be eternal are, at their core, irrational. Pandemics end. There could always be a new variant that proves as contagious and more deadly, which emerges before the election. But it is more likely that things will get better in the months ahead rather than become worse. Putting it in political terms, Marist’s Miringoff pointed out, “Some of the current predictions about Biden have been made at the height of a spike in cases. A month from now, things may be entirely different.”

Given the missteps of the last few months, Biden may personally never receive full credit if the pandemic recedes into the background. But the Democrats’ fortunes may rebound as the national mood lightens. Back in June, according to the Gallup, 89 percent of Americans believed that the coronavirus crisis was getting better. By December, that number had dwindled to a stubbornly cheerful 31 percent. A few months of sharply dropping caseloads and no frightening new variants could restore much of the optimism of mid-2021.

As Fran Lebowitz pointed out, no one living has been down this road before, unless you count the centenarians who were just squalling babies during the 1919 influenza epidemic. There are no guarantees about anything in a post-Covid America, other than that the blessed moment should arrive eventually. The height of folly would be to fail to appreciate that sooner or later there will be a collective burst of euphoria unlike anything America has experienced since V-J Day.