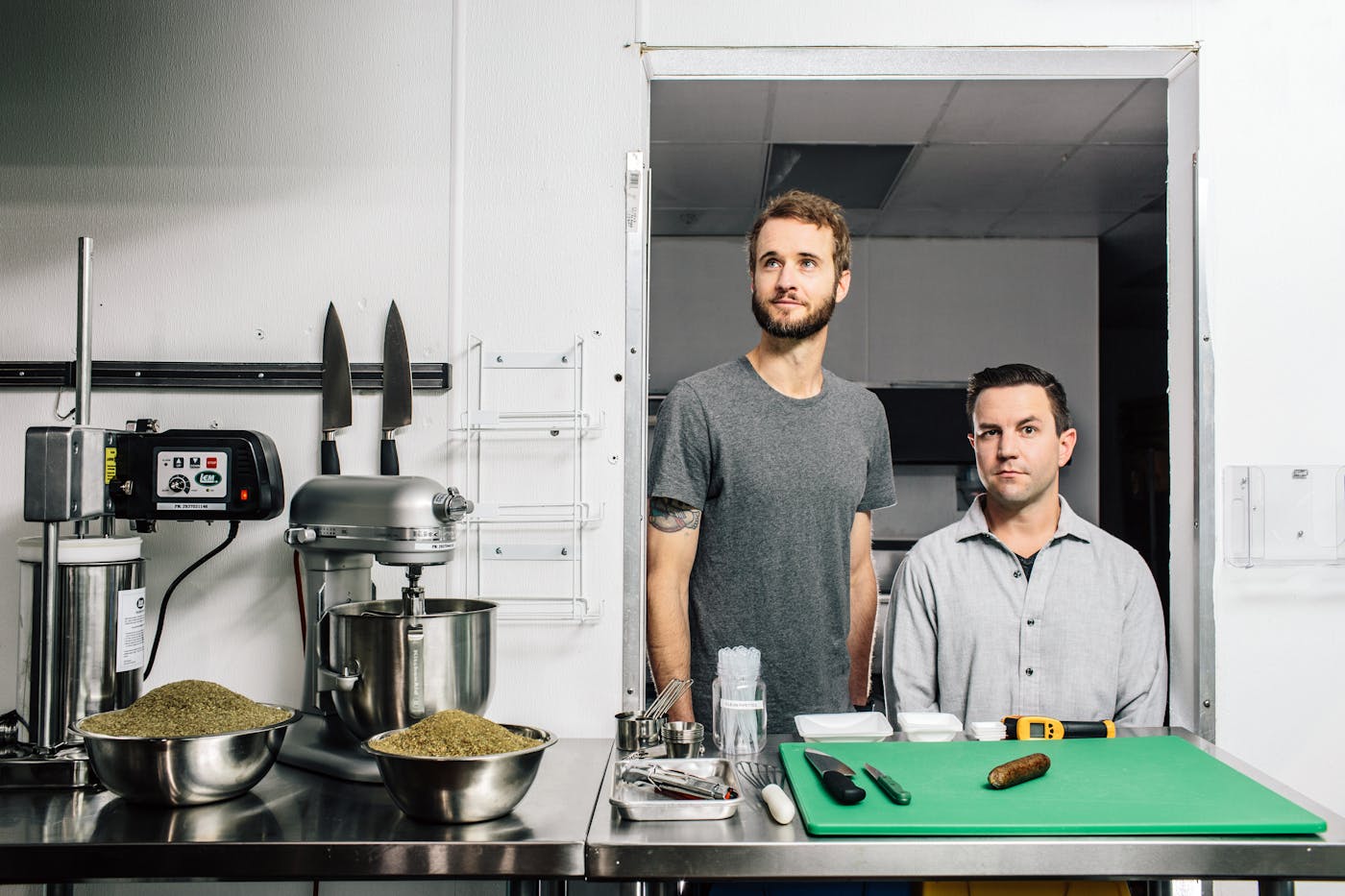

“Why haven’t you eaten cultured meat today?” That was the question posed to me on a breezy spring day by Brian Spears, the wiry, boyish CEO and co-founder of New Age Meats. We were sitting just outside his company’s food-science lab in Berkeley, housed—appropriately enough—in a shuttered burger joint. The company’s debut product will be an Italian pork sausage, layering the proteins the start-up grows on to plant-based “scaffolding.” You might know cultured meat as lab meat, animal proteins cultivated from cells rather than slaughter. But as New Age chief operating officer Derin Alemli amiably informed me early in my reporting, the first rule of lab meat is “don’t call it lab meat.”

In the last decade, cellular agriculture—the preferred term for New Age’s nascent sector—has attracted $7 billion worth of investor and venture capital funding from the likes of Bill Gates, SoftBank, Merck, and Tyson Foods. Much of that money has gone to companies producing cultured chicken, pork, and seafood. Others are hard at work making dairy, leather, or gelatin. A company called Ceratotech even tried its hand at rhino horns. There are now more than 70 cultivated meat start-ups worldwide. Late last year, after Singapore’s Food Agency granted regulatory approval, a private members club in the city started selling $17-a-plate chicken nuggets made by the San Francisco–based Eat Just.

The simple answer for why I had not eaten cultured meat that day was that I was not in Singapore, and Spears had not offered me a sample. The real answer is a bit thornier.

Like most Americans, I do eat meat, if a good deal less than the nationwide average of 274 pounds per year, not including fish or seafood. That figure is a problem for the planet: Meat production spews out methane and carbon and snaps up tracts of forests that once captured carbon from the atmosphere. Altogether, meat and dairy production is responsible for 14.5 percent of the planet’s greenhouse gas emissions. A February 2019 report from EAT-Lancet finds that to keep warming below 2 degrees Celsius, the United States needs to decrease meat consumption by 86 percent.

And the consequences of our overreliance on meat aren’t solely environmental. Premised as it is on both deforestation and antibiotics, industrial animal agriculture, which crams species and their pathogens up against one another, is a prodigious vector for all manner of diseases. In 2019, for instance, African swine fever is estimated to have killed up to 40 percent of the world’s pig population. Meanwhile, worker abuse is ubiquitous. Horror stories have emerged from meatpacking facilities of employees—disproportionately immigrants and women of color—working shoulder to shoulder with scant protections at the height of the pandemic. According to one study, livestock plants accounted for between 3 and 4 percent of all Covid-19 deaths in the United States up through July 2021. Of course, meat production has long been grueling, bloody work, requiring intimate contact with tools built to rip through flesh. Workers regularly report injuries more severe than those in sawmills, construction, and oil and gas drilling combined to the Occupational Safety and Health Administration. Human Rights Watch found that, between 2015 and 2018, meat and poultry workers lost body parts or were hospitalized for in-patient treatment every other day.

Its many ugly repercussions notwithstanding, meat consumption is exploding, including in those low- and middle-income regions that have historically consumed less meat-intensive diets, such as Southeast Asia. Global meat consumption is projected to grow by 1 percent this year. Even conventional factory farming will struggle to keep up with ballooning demand.

In the absence of an explosion of sustainable animal husbandry, global meat rationing, or a collective vegan epiphany, it is welcome news that cellular agriculture has grown up so fast. A now decade-old and somewhat controversial life-cycle analysis of cultured meat estimated that its widespread adoption could reduce greenhouse gas emissions, land use, and water use by up to 95 percent each compared with conventional meat production. And the sector’s growth has been astonishing; the first bovine embryonic stem cell was isolated only in 2018. Indeed, my tour of the Bay Area’s burgeoning cell ag scene inadvertently ended up mirroring the trajectory of the field itself: On my first site visit, I slipped into sterile Crocs and a lab coat to peek at shake flasks and under cell culture hoods. By the end, I was handed a hard hat and a high visibility vest to tour the buzzing construction site of what will be the world’s largest cultured meat production facility.

Almost none of that progress has been thanks to the U.S. government. While the Netherlands, Israel, and Singapore have all thrown considerable state support behind alternative proteins, the sector here—the world’s largest—has sprouted up with precious little support for basic research, let alone the generous subsidies that flow to conventional agriculture. Yet what could be seen as a shining example of private-sector dynamism is cause for concern among some of the field’s most enthusiastic supporters.

“Because of the lack of public funding, companies are making claims that they’re going to put products on the market in two or three years,” said Isha Datar, the executive director of the nonprofit New Harvest. “Meanwhile, there is no infrastructure to support determining the safety of the product, and no public literature on the safety of cultured meat.” The small team Datar oversees provides grants to generate a body of independent, peer-reviewed, public-domain research on cellular agriculture, furnishing funds that might ideally come from federal agencies. Datar envisions New Harvest as building “the infrastructure for a new field” that won’t, she hopes, start to resemble the industries it aims to disrupt. “Historically, the introduction of technology into agriculture has only led to more consolidation, and that only leads to less transparency,” Datar added. “Part of me wanted to be in this field to see if it can be steered in a different direction.”

Building out public-sector support for cellular agriculture in the United States—from research funding to rigorous regulations to industrial policy—isn’t just key to building a better cultured meat industry. It could also be a deciding factor in whether this desperately needed climate innovation takes off at all.

San Francisco’s Dogpatch neighborhood was reportedly named for the packs of strays that hunted for scraps from a now extinct row of nearby slaughterhouses, where industrial meat operations could discard entrails into marshes and mudflats. Butchertown, just south of Dogpatch, was home to tanneries, fertilizer plants, and tallow works as well—factories housing processes too fetid and violent for the city center, which fed it nonetheless. Today, the strays are long gone. The factories and ironworks that once populated working-class Dogpatch have been replaced by luxury condos, Third Wave coffee shops, and office space for the tech and creative industries that exploded in the Bay Area after the dot-com boom of the 1990s. It was in one such building that I met Justin Kolbeck and Aryé Elfenbein of Wildtype Foods, a cultured salmon start-up. “It wasn’t always our first choice to go get venture capital,” Kolbeck said of the company’s early days. In 2015, when they were first getting started, the pair spent weeks applying for several government grants, to no avail. A comment from one National Science Foundation reviewer stood out. While the proposed technology looked “very interesting,” the reviewer’s opinion was, “we still have enough resources and land to provide natural food for everybody on our planet.” (The NSF has not responded to a request for comment.)

Kolbeck and Elfenbein are happy with where they ended up. Wildtype’s investors have been supportive, and they’re in the process of building a pilot production facility a few floors below the combined lab and office space where we talked. Still, they wonder how things might have been different had those initial grants they applied for come through. “We would have taken some bigger risks scientifically early on,” said Elfenbein, a soft-spoken M.D./Ph.D. who still works one day a week as a cardiologist at a nearby hospital. He said it was helpful, now, to be under pressure to create a product: “With every day that goes by, our environment is in a slightly worse place.” But starting out with that pressure discouraged some of their wilder ideas, “in favor of very quickly minimizing the risk at every stage.”

“There’s an alternative universe,” Kolbeck added, “where government and philanthropy fund enterprises like ours, and the products are to benefit everybody. That model just doesn’t really exist in the U.S.”

Since rejecting Wildtype’s initial applications, the National Science Foundation has warmed up to cellular agriculture. Last year, the government awarded its largest grant to the field. As part of a program dedicated to what’s known as convergence research, which brings multiple disciplines together to address urgent societal problems, the NSF awarded $3.5 million to the Cultivated Meat Consortium, housed at the University of California, Davis.

The aim of the cross-disciplinary program—spanning biotechnology, agriculture, food science, and bioprocessing—is to better understand cellular agriculture, and work out the many remaining kinks standing in the way of widespread adoption. The basic mechanics aren’t complicated. A biopsy is taken from a live animal—New Age took one from a pig named Jessie—and brought back to a lab. Under sterile conditions, scientists feed proteins, salts, and growth factors (“media”) to isolated cells from that sample, either at the small scale in a lab, or in a gigantic steel tank known as a bioreactor, where they can propagate en masse. The result won’t be a chicken cutlet or baby cow, but tissue from whichever stem cells the engineers have chosen. The result is meat, although not—in its raw form—the kind that you would want to eat. Plant-based ingredients and spices need to be added in order to transform it into the concoction of preservatives, starch, and animal proteins that combine to make a chicken nugget, for instance. It’s easier to create something that is biologically chicken, in other words, than to make the stuff taste like it. Done right, the results are reportedly indistinguishable from the real thing. Raffaella Boulter—the events and programming manager of 1880, the Singapore club where Eat Just launched its chicken—said guests who tried it “could barely tell the difference.” 1880 has now stopped offering the chicken nuggets, owing to “delays in production,” but hopes to put them back on menus by the end of the year.

Despite the number of times company founders used the word “inevitable” while talking to me, there’s still no guarantee that the average American will be chowing down on cultured surf-and-turf anytime soon. “As an academic, I have to be a healthy skeptic,” the chemical engineer David Block told me, “and I don’t think that we know for sure yet that this is going to happen.” Major technical hurdles remain. There is still no dedicated cell bank of isolated animal or seafood cells. Costs remain prohibitively expensive, stemming largely from the media used to feed ever-multiplying armies of cells. Muscle fibers formed from use are especially difficult to replicate, because they require some physical exertion to develop. And some of the more unseemly elements of the cell ag process are also its most cumbersome. In 2018, New Age Meats celebrated having eliminated fetal bovine serum—extracted from the blood of cow fetuses—from its “stem cell and fat cell culture medium.” But there is currently no cost-effective alternative to other animal-derived growth factors, although a few companies are working to scale up a serum-free culture medium that as of last summer cost $376.80 per liter. Until such projects take off, Block explained, building a cellular agriculture industry will require simultaneously building out an animal-reliant growth-factor industry that isn’t currently producing the quantities that would be necessary.

There are large and small ways the government could help with these sorts of problems. A proposed wish list from the Good Food Institute, a nonprofit booster of cellular agriculture, requests $2 billion for research and development, redirecting $50 million of existing NSF and USDA funds toward alternative proteins research. At a time when Democrats are floating a $3.5 trillion infrastructure package, there’s arguably room to think bigger. Simply adding line items for cellular agriculture into the request for proposals put out by different agencies could go a long way, Block reasons. Any number of agencies could get involved. Basic research of the sort the NSF is funding at UC Davis could be expanded. Companies working on infant health and nutrition could be eligible for grants from the National Institutes of Health. The USDA regularly hands out grants for increasing the food supply, and NASA has a keen interest in learning how to create meat without animals in conditions where they can’t survive.

Beyond research is the challenge of building up a talent pool that could staff a thriving cell ag sector. Several companies have had trouble recruiting employees from extremely niche fields like tissue and bioprocess engineering, and as difficult as it is to find people with high-level skill sets, finding people who know how to apply them to food is more challenging still. Those labor pools take time and money to build, and for now Davis’s and Tufts University’s programs remain among the only ones with more than a single interested faculty member. A grant program announced tomorrow wouldn’t begin handing out funds until after a three- to six-month evaluation period. Faculty then need to recruit students, who in turn have to actually do research and go through extensive peer review processes. That leaves roughly two to three years before grants will bear any fruit, and none are on the immediate horizon. House Appropriations Committee Chair Rosa DeLauro has argued that research into alternative proteins should receive funding from the USDA that’s at parity with research into conventional agriculture. “The United States can continue to be a global leader on alternative protein science,” she told Secretary of Agriculture Tom Vilsack in April, “and these technologies can play an important role in combating climate change and adding resiliency to our food system.”

Concordia University political economist Jan Dutkiewicz, who has published extensively on both cellular and traditional agriculture, advocates for what he calls a Green New Deal for Clean Meat. A first step could be simply to redirect the enormous amount of public support that helps stock Costcos around the country with $5 rotisserie chickens. The support comes in the form of direct subsidies, but also academic grants that train up successive generations of Ph.D.s who figure out how to render factory farms more brutally efficient. Beyond the more traditional forms of R&D funding Block described, the government could use its enormous procurement power to become the country’s biggest buyer of cellular agriculture, putting it in Army mess halls and school cafeterias. More ambitiously, the government could build a pilot production facility, housed at a university like Davis, where smaller companies could work out scaling and safety problems alongside researchers. The economist Mariana Mazzucato—who helped design the European Union’s innovation agenda—suggests that setting out missions for the economy can foster a more active and productive relationship between the public and private, where the state helps shoulder the risk of emerging technologies—a role it’s played historically—but also shares in the reward. Though venture capitalists are leading the charge now, a “moon shot” mission for meatless meat may not be out of the question if lawmakers intend to take climate change and food security seriously. “Maybe you don’t need any progressive policy” for cultured meat to take off, Dutkiewicz said. “But will it work to its maximum potential? Unclear. Who will have power in those value chains?”

The Bay Area is a fitting epicenter for cellular agriculture: in the heart of a crunchy farm-to-table mecca and a short trip from Silicon Valley. Founders seem to split the difference. Spears, for instance, discovered his calling in the sector after feeling unfulfilled by his job in industrial automation and spending months backpacking alone in Europe and Asia. He described having found inspiration in the Japanese concept of ikigai, “a four-way convergence of what you’re good at, what you’re passionate about, what the world needs, and what the world will pay you for.” Though understandably more bullish than outside experts about the near-term prospects for getting to market, Spears and the other cell ag entrepreneurs I spoke with weren’t the hard-core libertarians one might expect from tech start-ups. Several want the state to play a bigger role.

Mike Selden, the CEO of Finless Foods, greeted me at his company’s headquarters in Emeryville, an industrial strip between Berkeley and Oakland known for malls and biotech. The 1980s-style building now serving as its home base used to house a company called Cartridge World before Finless created a custom-built lab inside. It’s now cultivating the start-up’s signature product: bluefin tuna, the giant, majestic creatures that can live up to 40 years if they aren’t killed off to make sushi and tender, fatty steaks. Replicating the fish from scratch means taking cells harvested from a real bluefin in partnership with one of the company’s earliest investors, a seafood company based on a remote island in Japan. The cells are then multiplied and scrutinized en route to forming fish. The wooden box lab in the office is currently doing this at a scale that fits on a lab bench. About 10 blocks south, Finless—like most of the companies whose representatives I spoke to—is building a pilot facility that can produce at a far higher scale.

Desks on the upper level of Finless HQ are adorned with mini sea-creature plushies, an ice breaker for Finless employees when they start. (There are now 15 employees in total.) New hires choose a creature and relate their lives to it at their first meeting with the full team. As one of the first employees—along with his co-founder, Brian Wyrwas—Selden was somewhat unoriginally assigned bluefin tuna post-facto once the tradition began. He stumbles through when I ask him to answer the prompt. “I’m very large, just like a bluefin,” said Selden, who’s a bit over six feet. “I am an apex predator just like the bluefin, and not in a bad way, but in a good way.... I think I got a C+ on the assignment.”

Before starting Finless, while still a cancer research associate at New York’s Mount Sinai Hospital, Selden had been planning to do a Ph.D. in cellular agriculture on a New Harvest grant. He ended up working for Datar in New York, and through that experience met investors interested in getting a company like Finless off the ground. He’s also a member of the Democratic Socialists of America, and he doesn’t see his job and his political commitments as being at odds. The project of creating cultured meat is a “very supply-side change,” he said—the point is to shift whole supply chains toward sustainability. “It’s not about individualistic consumer choice.”

When Finless was just starting out, its tuna was priced around $300,000 per pound. The cost of the product is now approaching parity with restaurant prices for bluefin, which are high because the fish—which can weigh up to 2,000 pounds—are nearly impossible to farm; a single bluefin was auctioned off in Japan last year for $1.75 million. Finless hopes to drive the price down even lower, but choosing a luxury flagship item will help the company compete with conventional seafood more quickly before expanding out to different kinds of seafood. The growth model is loosely similar to that of Tesla, sans the electric carmaker’s extremely online CEO, legion of rabid fanboys, and labor law violations. “We’re hoping to wean people off of tuna by making something that actually isn’t just better from an environmental perspective and a moral perspective but that is more affordable and tastier,” Selden said, noting that the product will also lack the high levels of heavy metals found in wild caught fish. In August, Finless announced it would be putting a plant-based tuna on the market next year in a bid to start becoming a food company, and move away from being “just pure R&D.”

Selden doesn’t want to oversell his project. He’s tackling only one corner of a broken food system. And in an ideal world, much of the research he’s doing might be open source and performed in the public sector. For now, just about every road to cultivating animal protein is paved with private cash. “We’re not going to save the world from capitalism,” he told me. “We’re a company. That’s not what companies do, and it’s not what companies can structurally accomplish.” Success for his or any other cultured meat company looks like becoming a multinational corporation. That brings the benefits of scale, he said, along with the dangers common to continent-spanning supply chains that demand the large-scale extraction of surplus value: “You shouldn’t just trust the word of an entrepreneur or CEO that they’re going to do the right thing, because we’re not structurally incentivized to do that.”

Even at this early stage, Selden and other founders are having to push back against the impulses of investors keen to keep as much of their work as possible proprietary. Spears noted, “Companies have said: Yeah, we filed a patent, and we spent a lot of money to do it. Why? Investors wanted it. We hear that over and over again: Investors wanted it.” He made it clear to his company’s investors early on that he wouldn’t prioritize filing patents, and he declined to work with those who disagreed. Chasing patents, he felt, was a waste of resources compared to the more valuable project of taking a product to market. But the choice wasn’t only because scrambling for patents was a waste of time and money; it also grew out of distaste for how private enterprise tends to treat intellectual property. “The mindset in the U.S. is that individual companies own that intellectual property,” Spears said, but IP that’s developed with support from public funds should benefit “the people and the country.”

Datar envisions “a totally new IP regime for cell ag that doesn’t resemble biotech as we know it.” The disaster of the global vaccine rollout has brought unprecedented attention to the Byzantine world of pharmaceutical patents. Thanks to aggressive corporate lobbying, decades-long patents are protected by a thicket of transnational rulemaking at the World Trade Organization. Despite ample manufacturing capacity, countries throughout the global south have been unable to produce and distribute vaccines, thanks in part to ironclad IP protections. That history offers a troubling preview of how other lifesaving technologies might be apportioned, including those needed to keep global warming below 2 degrees Celsius. Technology transfer—opening up green technologies—has been a long-standing demand from the global south within the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. Setting technology transfer as a baseline at this early stage of cellular agriculture’s development could (optimistically speaking) set a precedent that discourages other sectors from using patents to charge exorbitant rents for everything from cultured salmon to clean energy. “If this tech really is so disruptive, why don’t we disrupt a bunch of stuff?” Datar said. “IP can be one of the things that we disrupt.” She wasn’t against IP in general, she clarified, but thought patents should be used primarily as “a tool for disclosure rather than exclusion.”

Shouting over the din of his active construction site, I asked Upside Foods CEO Uma Valeti—another cardiologist—whether he intended to patent some of the processes and technologies used to cultivate his cell-cultured meat, poultry, and seafood. His company, the sector’s largest, houses 100 employees at its Berkeley R&D facility. Valeti did intend to patent his technology, he said: “Investment needs to come in so we can start lowering the cost and building production facilities that can scale, and in order to do so we have to start from a really strong basis of protecting the value.” But he didn’t intend to patent all of it, or hold on to the patents forever. Ultimately, he wanted to be part of helping meat production reach a different scale—“so we can start getting to some of the climate goals that we’re talking about.”

The rapid and venture capital–led rise of the cellular agriculture sector has posed serious concerns among those leery of food as a new frontier for tech. Everyone from Whole Foods CEO John Mackey to food writer Mark Bittman have criticized “higher-tech vegan meats.” Like-minded critics of corporate agriculture believe that investing in cellular agriculture could lock in our reliance on corporate-made processed foods and prevent a shift toward more plant-based protein and smaller-scale agriculture. They fear that cultured meats (or “in vitro processed meats,” as some have called the products) will evade regulatory scrutiny, and they see the lack of disclosures from companies about their ingredient lists and production processes as a bad sign. Michael Hansen, a senior scientist at Consumer Reports, said that while he thinks cell ag could “theoretically” be a “useful thing,” there are real dangers. For one, existing tissue banks for pharmaceutical uses are highly prone to contamination. The culture media used to grow cells are rife with biologically active ingredients that could carry risks for human health. “The quality of the cells you’re producing is going to in part be the result of what you’re feeding them,” Hansen told me. None of that information on inputs has been published, as companies voluntarily pledge to excise things like fetal bovine serum from their production process, without regulators asking for receipts. “Telling people this is going to be exactly like meat isn’t enough. If that’s true, show us the data. And they haven’t.”

The Center for Food Safety, a watchdog group, filed an unsuccessful lawsuit last year alleging that the FDA had been too quick to deem soy leghemoglobin (“heme”)—the ingredient that makes Impossible’s almost entirely plant-based burgers “bleed”—safe to eat under its existing rules on additives. The company Perfect Day was able to bring its animal-free whey protein to market using the agency’s GRAS Notification Process, where it makes the case that its products are Generally Recognized as Safe and waits to see if the FDA objects. It didn’t, and Perfect Day whey is now for sale in Brave Robot Ice Cream pints around the country.

“These are products that haven’t been on the market before, and it should be a requirement that they undergo deep safety assessments,” said Dana Perls, food and technology program manager for the environmental NGO Friends of the Earth. She worries that as things stand, assessment is virtually voluntary. “We need to have outside reviews, other than the companies claiming their own data is sound and safe.” In 2019, the USDA’s Food Safety and Inspection Service and the FDA entered into a formal agreement, establishing a division of labor between the two agencies as to which cultured meat and seafood products each would oversee. In addition to holding public meetings, the two agencies have also formed three joint working groups aimed at addressing premarket safety, jurisdictional boundaries, and labeling, and are consulting actively with companies in the sector. The FDA solicited comments from companies and the public on how to label cultured seafood last year. Another such proposed rule from the USDA—which will cover meat, poultry, and certain kinds of cultured fish—was as of publication under review by the Office of Management and Budget. After review, the rule will go out for public comment. In other words, regulatory approval isn’t right around the corner. When it arrives, advocates fear it won’t be nearly stringent enough, and will rely too heavily on the GRAS process, which allows companies to self-report whether their products are safe. “There should be required safety assessments for the ingredients and the whole process,” said Hansen, the Consumer Reports scientist. “It’s looking like that’s not what FDA and USDA are going to do.”

“The regulatory framework for oversight of foods made from cultured animal cells is already in place,” an FDA spokesperson said over email, adding that the joint FDA-USDA effort has committed to consulting with individual companies before they go to market, and is eager to work with them to ensure their products comply with the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act. A spokesperson from the USDA told me that the agency “does not intend to issue any new food safety regulations for the cell-cultured food products under its jurisdiction.” Existing regulations, the USDA spokesperson added, already cover food production technologies involving biological systems and biotechnology. “Following a completed safety consultation, the FDA intends to conduct routine inspections on an ongoing basis,” the spokesperson added, and will oversee “cell banks and facilities where cells are cultured, differentiated, and harvested.” Neither spokesperson responded directly to questions about disclosure.

Some regulatory deference to industry isn’t unique to the cellular agriculture sector, of course. Yet practices that benefit incumbent protein producers could hinder up-and-coming ones, whose products already face skepticism from a meat-loving American public and a GOP eager to gin up a culture war around the left’s designs on its hamburgers. Consumers deserve—and will better trust—products that are well-vetted, but cell ag companies aren’t putting their production inputs and processes on full display, because regulators haven’t asked them to yet. They are accountable to investors who are not keen to see them share their trade secrets with the world. Until there is a regulatory process requiring thorough disclosures on things like ingredients, supply chains, and safety protocols, businesses have no incentive to make them.

For Datar, it’s also important that the basis for regulation be built on something other than the good word of companies. Yet while New Harvest is trying to flesh out the ecosystem that might provide that basis by backing public-domain research, Perls, of Friends of the Earth, sees any federal investment in cell ag as a kind of moral hazard. The government and investors, she argues, “should be focused on helping to transition our food system to regenerative, diversified, family-friendly farming at this moment in time. Not cellular agriculture.” At least conceivably, it is possible to do both.

At Upside Foods, Valeti’s answer to concerns about transparency is a folksy one: windows. Flanking the cavernous, currently wire-strewn cultivation room of bioreactors are a kitchen and tasting area with observation panels for visitors to peer in, not unlike a brewery. David Block, whose expertise is in fermentation optimization, assures me the atmosphere will be a bit less relaxed than guys in T-shirts showing off their hops. To comply with food safety standards, those on the floor will wear hairnets and lab coats to prevent contamination. Cultured meat fermentation is an aerobic process requiring tubes to carry gases in and out, thus more complicated and vulnerable to pathogens than the anaerobic conditions that create wine and beer. But the general design principle is the same. Putting big steel tanks on display is meant to drive home the difference between the secretive slaughterhouses of today and the food factories of tomorrow. “Meat’s going to be made in front of you,” Valeti said. “You can come and visit where meat is made, and it’s going to be a part of where you live and where your kids grow up. It’s going to be local.”

About 50 people will work at the facility in San Francisco’s East Bay area, Valeti said. Behind the cultivation room—out of the public eye—will be a control center, a food science lab, quality control and inspection areas, and a fabrication room for machining and tooling. Among their other jobs, staff will monitor meat production, mix feedstock (media) for the cells, and maintain the facility and its phenomenally expensive equipment; Block estimates that a 25-gallon fermenter could cost upward of $350,000. They’ll also process what’s pumped in from the cultivation room to be shaped. “Some people use the term wet mass,” Valeti noted about that part of the process. He prefers a rebrand: “We harvest tissues.”

Just as electric vehicles won’t decarbonize transportation, cultured meat won’t fix a broken food system so much as mitigate the destruction caused by its worst actors. New products are no substitute for any of the sweeping changes required for sustainable calorie delivery: investing in sustainable agriculture, breaking up monopolies, and starting to peel back the $38 billion spent each year subsidizing the U.S. meat and dairy industry. Still more challenging is the fact that diets really do need to change, particularly in the West. Food systems are driven by personal choice in a way that energy grids simply aren’t. “The average person wants to flick their light switch and have the lights come on,” Dutkiewicz pointed out. “Most people would be happy for it to come from a low-impact source. People do make consumer choices when it comes to food multiple times a day. They vote with their forks, and, even within their bounded options, many people—given access and money—can choose to eat differently.”

That choice doesn’t necessarily have to be a sacrifice. If the government rebalances subsidies and enacts a tight regulatory regime that will ensure high labor and safety standards, cultured meat has the potential to be more than a one-to-one substitute to be endured. Instead of picking up slimy trays of shipped-in ground chuck, union workers in the Midwest could brew up Wagyu beef like a golden pint of craft beer. “We want to make bluefin for the price of albacore and basically see: Are people going to eat bluefin instead of albacore? If not, we’ll make albacore, too,” Selden told me. “Anything that’s specific to one locale you could make a worldwide commodity that anyone can get.” The French company Gourmey is similarly working on bringing cultured foie gras to the masses. As Dutkiewicz, the political economist, puts it, “This is about democratizing hedonism.”

There is nothing inherently evil or liberatory about cultured meat. Down one path is a new class of green-tinted corporate overlords peddling dubious slabs of meat spawned behind closed doors with fossil-fueled power, across extractive supply chains. Down another is something like Dutkiewicz’s vision, multiplied out across continents. A new food system could drastically reduce emissions and free land and labor now used to slaughter billions of creatures, delivering not just food security but luxuries previously reserved only for the one percent: a cultured chicken in every pot.