When the famous Blue Wave of 2018 swept Democrats back into control of the House of Representatives, it crested over many long-held Republican districts. This included California’s Central Valley agricultural region, where Democratic engineer and entrepreneur T.J. Cox bounced GOP dairy farmer and three-term Representative David Valadao by just 862 votes.

This instantly set up the expensive 2020 Valadao-Cox rematch. Including independent expenditures for both sides, the race combined to cost $24.3 million. Valadao would win his seat back by 1,522 votes, but he trailed Cox in fundraising for most of the race. To stay financially close, Team Valadao employed several unusual tactics involving its political action committee—known as a “leadership PAC”—that ultimately provided his campaign with upward of $120,000 in extra campaign cash, mostly down the stretch.

A review of Valadao’s 2019–2020 Federal Election Commission fundraising and expenditure filings revealed the use of at least one of these tactics that could be arguably illegal. Another was questionable, and others were legal but appeared to skirt the intent of individual campaign donation limits.

Valadao was hardly alone. FEC filings show he was among 126 Republican House candidates who took advantage of the same leadership PAC loophole that helped convert more than $2.8 million in donations to those PACs into campaign cash. This was achieved through complex swaps of nearly 800 donations between candidates’ leadership PACs and their main campaign committees. Though technically not illegal, the swaps show the lengths candidates are going to in order to move around large amounts of money to compete in ever more expensive House races.

“People should be incredibly shocked,” said former FEC Chair Ann Ravel. “The complexity of our campaign finance system seems designed to allow these end runs and obscure the original source of donations. This is a big part of why trust in government is at an all-time low.”

That leadership PACs are involved doesn’t surprise most critics. Ravel, who served on the FEC during the Obama administration, calls leadership PACs “just ridiculous.” They are governed by the same rules as any other PAC, which is to say very few rules. This has allowed incumbents and other candidates to raise money from sources who also maxed out to the main campaign committee and then use the money for almost any other purpose, including donating to other candidates.

“I know there were a lot of people who thought they were a great idea, but just the existence of leadership PACs has been problematic,” Ravel said. “Leadership PACs are so open to being used for so many unethical purposes, including ingratiating yourself with other candidates, and they have few regulatory limitations.”

One person who thought they were a good idea was former Congressman Henry Waxman. He arrived in D.C. as part of the post-Watergate class of 1974. After two terms, Waxman saw a chance to leap over several senior legislators and become chair of a House subcommittee. His strategy included the FEC approving his creating the first leadership PAC, which would allow him to donate to fellow Democrats, including those picking the next chair.

“In Congress back then, I could contribute $1,000 maximum from my campaign committee to another candidate, but I saw PACs could give up to another $5,000,” Waxman recalled. In the 2020 cycle, the limits for donations by an individual or campaign committee were $2,800 per election, and $5,000 per year from PACs.

The FEC approved Waxman’s request with just one prohibition. “I wanted to call it the Wax PAC,” he laughed, “but the FEC said I couldn’t name it after myself.” So he called it the L.A. PAC and raised $106,000 that first cycle. He donated to 29 different candidates, including the 1980 Ted Kennedy for President campaign. He also became chair of the House Subcommittee on Health and Environment.

Waxman said his larger goal was to help Democratic candidates, and over his career, he gave more than $3.6 million to Democratic colleagues and candidates. “We were giving away money. People were happy to get it. I probably spent more money on losing candidates than anyone else in Congress,” he said.

But unanticipated by Waxman or the FEC was how the simple rules governing a standard special-interest PAC would be insufficient for a leadership PAC. That’s because if organizers of a corporate PAC chose to spend their funds on something other than candidate donations, it didn’t matter much. But members of Congress soon learned they could spend their leadership PAC funds on everything from luxury travel and expensive European hotels to limousine service and concert tickets.

Today, only half of all leadership PAC money is used for Waxman’s original intention: donations to other candidates.

This has given leadership PACs their reputation as slush funds. But even so, one clear prohibition exists. Candidates may not use their leadership PAC funds to cover expenses by their own campaign. Yet for candidates locked in expensive races scrambling for every donation possible, all that cash sitting off-limits in their own PAC can be quite tempting.

In Valadao’s case, FEC records show his leadership PAC disbursed $179,561 in the 2019–20 cycle, and close to 75 percent of this was either converted into campaign cash or used to cover general campaign expenses. This included converting more than $65,000 into campaign cash by mutually swapping leadership PAC donations with 24 other GOP House candidates.

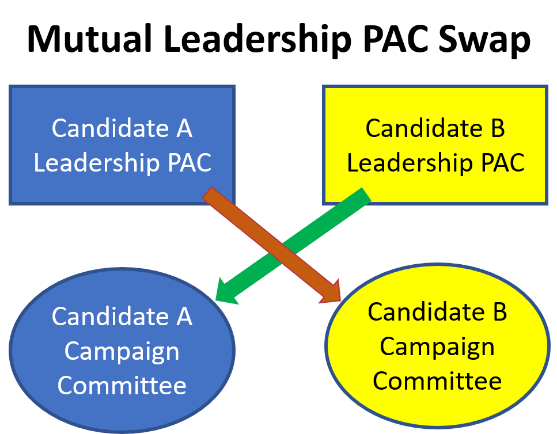

Most swaps of leadership PAC donations work like this. Candidate A donates an amount from his own leadership PAC to candidate B’s campaign committee. Candidate B’s leadership PAC in turn donates a similar amount to Candidate A’s main campaign account. This allows funds in both candidates’ leadership PACs to go down as their campaign balances increase. By shuffling money between these multiple entities, campaigns create a legal loophole since technically neither campaign is spending its own PAC money directly on its own campaigns.

The technique has been around for at least 10 years. In 2014, the Center for Responsive Politics, or CRP, reported on such swaps among incumbent senators of both parties. But as House races have become increasingly expensive, the tactic’s popularity has greatly expanded among House Republicans. Among House Democratic candidates, the tactic has taken deep root more slowly. According to a recent CRP data search for this article, Democrats in 2019–20 converted roughly 12.5 percent—or $354,300—of what House Republicans did. Fifty-six Democratic candidates did participate in at least one swap, but only five executed more than five. By comparison, 48 GOP House candidates completed five or more swaps.

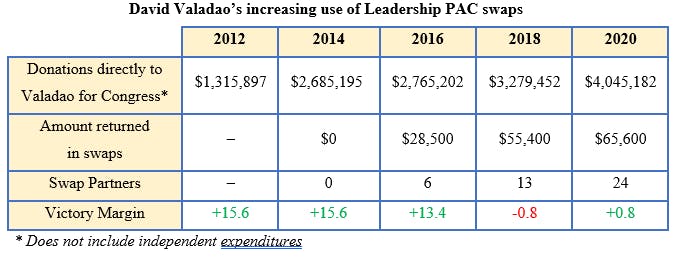

Valadao’s increasing use of mutual leadership PAC swaps follows the Republican trend. He first opened a leadership PAC in 2014 during his second term in office, but he made no swaps that election cycle. However, after that election doubled in cost, he swapped with six other candidates during the 2016 cycle. This doubled in 2018, with swaps with 13 candidates, and then nearly doubled again to 24 last cycle.

Since leadership PACs aren’t named after members of Congress, tracking the flow of money between candidate PACs and campaign committees isn’t simple. But for experienced campaigners—like Valadao’s Democratic opponent in 2018 and 2020, T.J. Cox—the transactions are highly conspicuous and maddening.

“It was making my head explode,” Cox said. “After all, why does a candidate [Valadao] who is not a current member of Congress have a leadership PAC to start with? For what purpose? It’s a practice everyone knows the Republicans do. I’m surprised, frankly, that the Democrats or anyone else haven’t highlighted it more.”

Cox was a rare member of Congress who didn’t have a leadership PAC last cycle. His explanation? “Being a frontline member and in such a costly race, we didn’t have an extra nickel to donate to anyone else. Mr. Valadao was in the same situation, but then why would they contribute money to anybody else? Other than they knew they would be getting a contribution back in return,” he said.

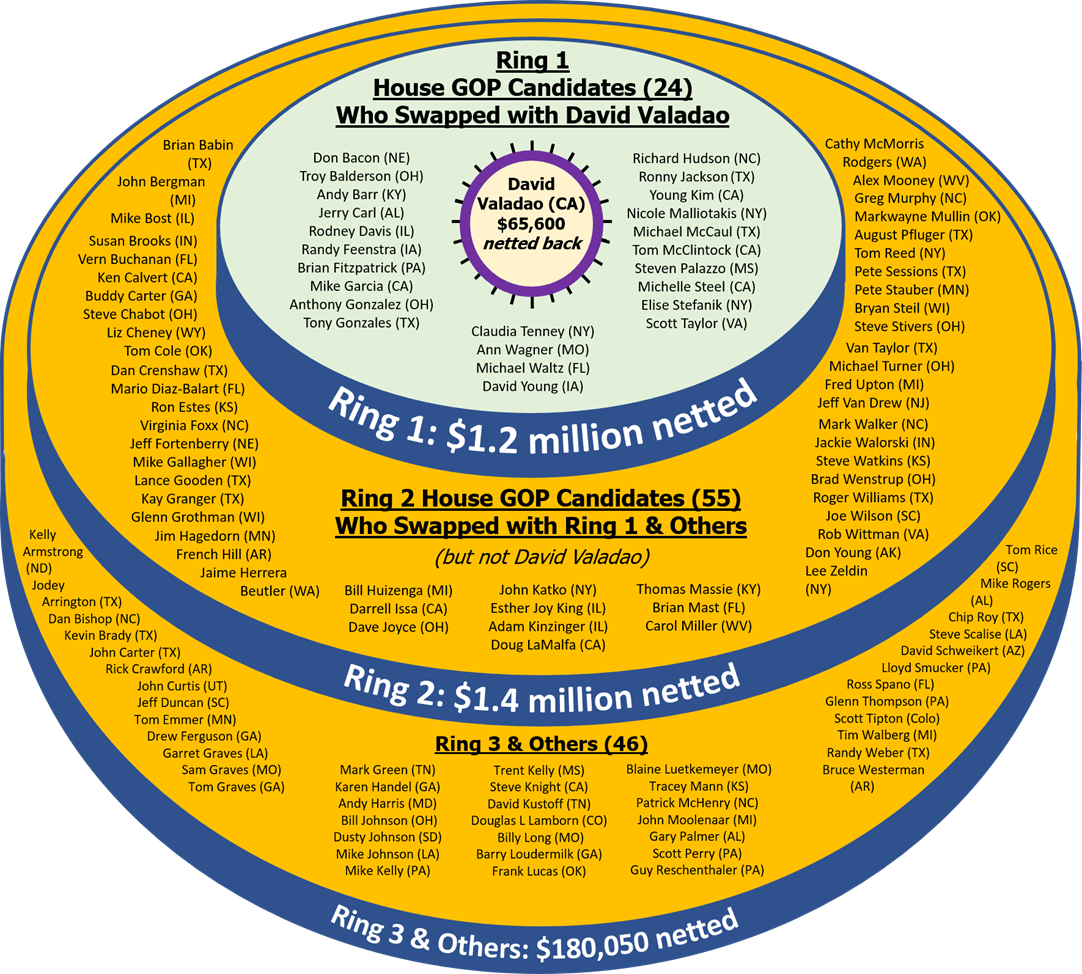

But even Cox was unaware just how extensively mutual leadership PAC swaps were employed by GOP House candidates in 2020. This included 113 incumbents, as well as 13 candidates seeking their first term. The diagram below illustrates the three rings of mutual swaps that expanded out from Valadao. He swapped with 24 candidates in Ring 1, which netted $65,600 back to his campaign coffers. These 24 in turn generated nearly $1.2 million in converted funds for their campaigns through swaps with each other and 55 other candidates in Ring 2.

The 53 Ring 2 candidates netted another $1.4 million in converted cash through their swaps. But in Ring 3, the rate of swapping slowed significantly, with just two of 46 candidates making more than two swaps each. All told, more than $2.8 million was converted, largely unnoticed, from leadership PAC money into usable campaign funds.

“Leadership PACs have become this less observed arm of candidates,” said Sarah Bryner, director of research and strategy with the D.C. watchdog group the Center for Responsive Politics. “Misuse is very, very difficult to regulate because the rules are so broad. Some leadership PAC activity might even look fishy to us but is within bounds of the acceptable behavior of FEC rules.”

Though Valadao served as the “ground-zero candidate” for this examination, the $65,600 he netted was far from the most last cycle. Six House Republicans netted more than $100,000 each from their swaps. Top was Ann Wagner of Missouri, who received back $148,200 for her campaign committee from 33 candidates. She was followed by Michael McCaul of Texas ($128,700), Rodney Davis of Illinois ($120,600), Andy Barr of Kentucky ($118,400), Washington State’s Jaime Herrera Beutler ($117,000), and Richard Hudson of North Carolina ($105,900).

As a loophole, the mutual leadership PAC swap is curious for another reason. Consider that it is a felony for one big donor to distribute, say, $80,000 among 20 friends and family for them each to donate to a specific candidate. However, it is completely allowable for a congressional candidate to take $80,000 in leadership PAC money, divide it up among 20 fellow candidates, and receive the exact same amount back from those candidates’ leadership PACs.

“I have never heard of leadership PACs mobilized to this extent,” said campaign finance expert and former FEC General Counsel Kenneth Gross, who served from 1979 to 1986. But he added there’s nothing illegal in any of it. “There is a limit to how much you can give to a leadership PAC and that it’s disclosed. The money also cannot be used for campaign expenses, but that is as far as the rules go.”

But another way Valadao’s team tapped its leadership PAC strikes many observers as a possible violation of campaign finance laws. This involved the campaign manager’s salary.

During the campaign, Valadao’s campaign manager, Andrew Renteria, was paid between $6,000 and $6,400 a month. From October 2019 to May 2020, he was paid completely by Valadao’s main campaign account, like any campaign staffer. However, this abruptly changed in the final six months of the campaign, when Renteria’s salary payment from the main Valadao campaign account dropped to $1,500 per month, and the monthly difference ($4,904, or 75 percent of his income) was paid by the leadership PAC.

The leadership PAC’s FEC filings described these payments to Renteria as for “Fundraising Consulting,” and they totaled just under $30,000. This had the effect of freeing up that same amount for spending on other campaign needs. However, one of the few clear rules of leadership PACs is that no funds can be used to pay directly for campaign expenses.

One campaign finance expert said the campaign manager probably did some fundraising work, but it was highly suspect that in the stretch run of a very competitive race, the campaign manager suddenly decided to spend most of his time on leadership PAC fundraising. After all, if Valadao’s fundraising needs demanded such attention, money raised for his leadership PAC technically could be used for end-of-campaign expenses.

Renteria now serves as Valadao’s chief of staff. Neither Renteria nor Valadao would return calls or emails for comment. The only response received came from Valadao’s congressional press secretary, who said it was “highly inappropriate” to attempt to reach either through Valadao’s government office.

In January, the campaign watchdog (and Cox donor) End Citizens United filed a formal complaint with the FEC about Renteria’s compensation through the leadership PAC. End Citizens United spokesperson Ellie Dougherty said it was clear Valadao’s top campaign staffer should have been fully paid as a campaign employee, as had been done in all previous Valadao campaigns.

“[Valadao] has run for Congress five times and knows full well that using his leadership PAC as a loophole to fund his campaign committee violates basic campaign finance rules.”

Not covered by the End Citizens United complaint was a similar shifting of compensation for the campaign treasurer. The treasurer handled FEC filings for both the campaign account and leadership PAC. For most of the campaign, the main campaign account paid about 75 percent of her compensation; however, in the last seven months of the campaign, this ratio more than flipped, with about 80 percent covered by the leadership PAC. This served to free upward of $32,000 in Valadao’s main campaign account that was instead covered by the leadership PAC.

Former Congressman Waxman said the entire system is out of control and needs to be reformed. He agreed it has come to resemble a network of corporate shell companies. “I think that is apt. You don’t really know where the money is coming from, and there is no clear disclosure. Money can go from one group to another group and get laundered in an independent expenditure. It can be coming from anywhere, especially at the end of a campaign,” he said. “It is just overwhelming.”

“You have to assume that real reform can’t come from the FEC as it is currently structured,” the Center for Responsive Politics’s Bryner said. “It has always been hamstrung. So you need oversight from Congress, which is technically a possibility, but Congress has always been really reluctant to regulate itself.”

As for End Citizens United’s FEC complaint about Valadao’s campaign manager salary, the FEC would not comment, as the status of all investigations stays confidential until resolved. But former FEC Chair Ravel said it’s unlikely the complaint will be resolved before the 2022 midterm election. This is partly due to the backlog of cases that accumulated when the agency lacked a quorum of commissioners for most of the last year and a half of the Trump administration.

Either way, the midterm fundraising machines have already revved up, and all indications are that mutual leadership PAC swaps will grow significantly in total dollars and participating candidates. Take the Valadao campaign in just the first quarter of 2021. Last election cycle, it didn’t complete its first mutual leadership PAC donation swap until September 2019. But in Q1, Valadao completed swaps with eight different GOP House colleagues.

Noteworthy is the fact that two of Valadao’s early swapping partners are House colleagues who made just one swap combined last cycle. The swap newbie is Representative Dan Newhouse, who completed five swaps in Q1 for $12,500 in quick campaign cash. Tom Rice made just one last cycle, but already has four under his belt netting $9,000.

And don’t bet against the Democrats expanding their use of the tactic this cycle. With just a four-seat advantage in the House, they will be hard pressed to resist matching the GOP’s every fundraising tactic.

Even Valadao’s two-time opponent T.J. Cox said he’s made no decision on a leadership PAC of his own for 2022. He’s technically in “exploratory committee” mode waiting to see how redistricting affects several Republican-held districts in his area. (House Minority Leader Kevin McCarthy and Devin Nunes represent neighboring districts.) But whether he re-ups for another Valadao rematch or challenges in a realigned nearby district, Cox does not relish all of our system’s fundraising gamesmanship.

“All the time, candidates go back and forth with each other and say, ‘Hey I have a maximum donor for you if you have a maximum donor for me.’ That’s happened once or twice with me, and I just don’t play that game,” he said. “Compared to any other country, the whole way we finance campaigns in this country is just crazy.”