What made

Bill Barr such a bad attorney general? The question is of more than historical

interest, as pundits have begun to grapple with the state of the Justice Department he left behind. Barr’s legacy is difficult to ignore—not least

since his successor, Merrick Garland, has shown

few signs of providing the sharp

break from the past that many wanted, or a reckoning with the department’s widespread

deterioration during the Trump administration. It is a

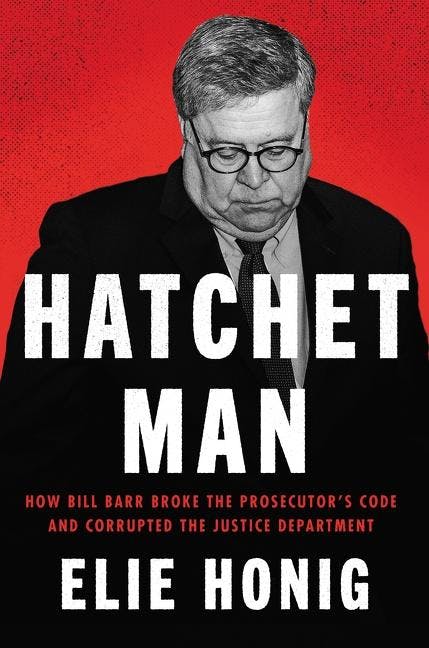

question that, in theory at least, Elie Honig sets out to answer in Hatchet

Man: How Bill Barr Broke the Prosecutor’s Code and Corrupted the Justice

Department.

Honig is among the many former federal prosecutors who rose to public prominence during the Trump years—a presidency dominated by high-profile legal problems and investigations as no other. He was a federal prosecutor in the Southern District of New York from 2004 to 2012 and, from 2012 to 2018, held senior positions in the New Jersey Division of Criminal Justice. He keeps a portfolio of projects that many modern legal commentators maintain—in addition to the TV gig, he writes columns, hosts a podcast, and maintains an active Twitter feed. He is currently a senior legal analyst for CNN, where, during the Trump years, you could often find him offering prosecutorial takes on the latest legal news about Trump and Barr—simple, to the point, and accusatory.

In Hatchet Man, Honig calls Barr a “liar” and “an eager political partisan,” and accuses him of using his position “to impose his own legal and philosophical views on how civil society ought to function.” The list of offenses is familiar: Barr’s “powerfully dishonest and manipulative” summary of the Mueller report; his “bizarre, unprecedented” interventions in the criminal cases against Trump advisers Michael Flynn and Roger Stone; his “takeover” of the Southern District of New York through the firing, in mid-2020, of U.S. Attorney Geoffrey Berman; the department’s “specious” defense of Trump in the lawsuit filed by E. Jean Carroll; and Barr’s “just plain wrong” assertions about supposedly widespread voter fraud during the run-up to the 2020 election. Through all of this, Honig writes, Barr “inflicted deep and structural damage on the Justice Department and its core principles.”

What ties these failures together? Honig’s thesis is that Barr did a particularly poor job because he “had never set foot in a courtroom to prosecute a criminal case.” Instead he had worked in the CIA, in the White House, and as a senior official in the Justice Department at various points from the early 1970s to the early 1990s. He did not learn about the work of a prosecutor “the hard way, by making mistakes and experiencing setbacks mixed in with successes.” It is a tidy and superficially appealing theory—one that tracks the intuition that people with government experience and expertise might be less corruptible and pliable than political newcomers. But its flaws and blind spots may reveal more about the assumptions of legal pundits—former prosecutors in particular—than it says about Bill Barr himself.

A large portion of Hatchet Man is in fact about Honig. Using vignettes from his own time as a prosecutor, he illustrates lessons that he learned—and, he argues, that an attorney general should have learned—on the job. One is that sometimes you have to run risks when you are investigating criminal misconduct. In the course of criticizing Barr for choosing to intervene in Stone’s sentencing, for instance, Honig notes (correctly) that “the dirty little secret about the sentencing guidelines is that they frequently yield recommended sentencing ranges that are overinflated.” He explains at one point why prosecutors do not actually go to crime scenes when an investigation begins (you could become a witness in your own case) and repeatedly returns to the sometimes perverse nature of the “unimaginable” and “intoxicating” power that young, low-level federal prosecutors wield.

At other times, the connections to Barr are strained at best. Honig provides an account of how he once drafted a criminal complaint with an agent by his side—something that prosecutors occasionally do when they want to complete the charging document as quickly as possible, since the agent is the source of the facts and this eliminates the hassle of working through multiple drafts from separate locations—which Honig describes (also correctly) as “a scene that you could see playing out in U.S. Attorney’s Offices across the country.” He uses the scene to criticize the DOJ’s refusal to open a criminal investigation into possible crimes that were “screaming out for further inquiry” following Trump’s shakedown of the Ukrainian president in July 2019. The implication is that Barr may have proceeded differently if he had once been a line prosecutor who had to make difficult charging decisions, but the suggestion is hard to take seriously. It also ignores the fact that career prosecutors at the department were integrally involved in the decision not to investigate Trump further, including a lawyer whom Honig praises in a separate chapter as a “veteran DOJ election law expert.”

Taking a step back, it is not hard to see that the relationship between prosecutorial experience, on the one hand, and competence and integrity, on the other, is not exactly airtight. Trump’s first attorney general, Jeff Sessions, was a line prosecutor, but he still did some awful things, including implementing the family separation policy—which, if we are judging by tangible rather than symbolic consequences, may have been worse by itself than the entirety of Barr’s tenure. Rudy Giuliani was once a well-respected prosecutor and was almost one of Trump’s attorneys general, but he has been a shameless and power-hungry political partisan ever since 9/11 made him a national political figure, and he recently had his law license suspended. Ronald Reagan’s second attorney general, Edwin Meese, had worked as a local prosecutor, but that did not prevent him from getting mired in several major controversies.

The argument that Barr suffered from being inexperienced is a difficult one to make considering that Barr is the only person since 1853 to have served twice as attorney general—the first time at the tail end of President George H.W. Bush’s administration. His two stints in the position make him the only single person in well over 150 years who could provide a natural experiment to test Honig’s argument: If his gap in experience was the main factor in his performance, that should be true of both of his periods in this role. But Honig himself writes that the first time around, Barr “completed [that] tenure without any legacy-defining failure or scandal.” That alone would seem to provide a significant complication for Hatchet Man’s argument.

There are some intriguing ways to try to explain how Barr’s performance could have varied so dramatically between his first and second stints. Perhaps the difference was Trump, who has a knack for bringing out the worst in people. Perhaps Barr undertook the same radical ideological transformation as many conservatives in the intervening decades—one heavily influenced by a hermetically sealed and self-reinforcing conservative media ecosystem, in which defeating liberals and maintaining political power has increasingly become the singular goal of the Republican Party, to the exclusion of any real policy agenda. Evaluating these possibilities would have required a serious effort to understand Barr and his life, as well as the changing political landscape between the first Bush and Trump presidencies, but Honig does not explore these possibilities or others.

In the narrowness of its scope, Honig’s book reflects the limitations of the prosecutorial methodology—a backward-looking exercise that usually involves taking a factual record, devising a totalizing explanation and narrative that fits it (the simpler, the better), and reinforcing the best facts for that account at every opportunity while doing your best to accommodate or explain away inconvenient ones. The methodology works best on relatively narrow and discrete events. It is not particularly well suited to exploring actions that occur in highly complex systems or that entail value judgments. (In fact, the professional imperative to simplify matters for the consumption of judges and juries can occasionally obscure more than it illuminates.)

Hatchet Man closes with an obligatory chapter on proposals for post-Barr reform. In Honig’s telling, Barr is the singular villain of his Justice Department. Honig goes to great lengths to exculpate the career workforce—writing, at one point, that there was “no visible degradation in the quality or integrity of their work during Barr’s tenure.” This is a gross and inaccurate simplification. Career lawyers were involved in virtually every controversial decision and effort undertaken by the department during the Trump years—some better known than others—including those, like the efforts to dismiss the Flynn prosecution and the Carroll lawsuit (and, as noted above, the declination over the Ukraine episode), for which Honig sharply criticizes Barr.

This is more than a problem for Honig’s presentation of Barr as the only meaningful actor in the department. That Barr and his deputies (and Sessions before them) managed so easily to bring the department’s career workforce to heel in various ways, some of which we are only now learning about, is an institutional and historical fact—a reality that is vitally important to understand and to work to prevent from recurring in the future. Honig also notably omits any discussion of the idea—rejected recently by Garland as well, albeit not surprisingly—of conducting a broad review within the department for improprieties that we do not yet know about.

Honig instead advocates for a series of relatively modest internal policy changes—some of which would be easier to operationalize (“revise the special counsel regulations”) than others (“reject Barr’s stated view of complete presidential prosecutorial power”), and some of which are questionable on their face given the ostensible purpose of the book. Honig argues that either Congress or the department should “clarify the prohibition on foreign aid” to specify that it “includes opposition research”—in order to make clear that incidents like the infamous Trump Tower meeting in June 2016 are illegal—but as Honig notes, it was Mueller who fumbled this question before Barr did. Honig also suggests that the department should “reinforce the policy restricting public commentary on pending investigations,” which, he writes, “shouldn’t need reinforcing, because it is already on the books.”

Other proposals from Honig present nuances that the book does not grapple with. Honig is rightly critical of the performance of the department’s Office of Legal Counsel—the office that concluded that the Ukraine whistleblower’s complaint did not need to be forwarded to Congress and that advised the White House that it could categorically reject the House’s subpoenas during impeachment proceedings. He argues that the department “should adopt a rule that once any OLC position has been rejected in a final ruling by the federal courts, that opinion is a goner,” but this would seem to include trial court rulings that remain subject to appeal, and it is far from clear that this is a good idea, particularly given a judiciary that was reshaped under the Trump administration.

There is a larger, unrecognized tension in Honig’s set of internal policy proposals, which is that it is hard to understand how they would meaningfully constrain an attorney general who wants to disregard them. He writes, for instance, that the department “should explicitly limit communications between DOJ staff and White House officials”—and indeed, the department may do that under Garland—but the sort of attorney general who is willing to speak with the White House on sensitive, politically inflected law enforcement matters is probably not the sort of person who will be deterred by an internal policy. Likewise, it is all well and good for the department to “formally encode and enforce” a rule governing the process for the recusal of the attorney general in circumstances presenting a conflict of interest, but would this have done anything to stop Barr from finding a way to intervene in whatever cases that he wanted? The answer seems obvious.

Honig also does not grapple with the possibility that serious statutory reforms might be more effective in addressing his concerns. The problems are legitimately difficult ones, and there would be obvious trade-offs in congressionally enacted rules—an internal policy change gives the department more flexibility—but it is hard to shake the feeling that Honig’s experience in the department, his government-friendly predispositions, and his confidence in the integrity and resilience of the career workforce are doing a lot of unexamined work here.

An early and interesting passage in Hatchet Man recalls how so many people, including Honig, misjudged Barr at the time of his nomination despite warning signs about how he would do the job. Honig said that Barr was “qualified,” “serious,” and “respected.” Former FBI Director Comey called him “an institutionalist who cares deeply about the integrity of the Justice Department.” Harry Litman—a former U.S. attorney under Bill Clinton, the legal affairs columnist for the Los Angeles Times, and a frequent television commentator—described Barr as “a strong person of principle.” Benjamin Wittes—the editor of Lawfare and another regular analyst on television—wrote that Barr had a “formidable mind and deep experience of precisely the right type.”

The department, of course, is now under the purview of Garland, who glided through the confirmation process with even more effusive praise and even fewer questions, based in part on the appeal of a dramatic arc. This was, after all, the man who was unjustly prevented from taking a seat on the Supreme Court in 2016, and he was reentering public life to help clean up the mess that Trump and Barr left behind in the department where he had once distinguished himself.

It is inconceivable that Garland could ever turn out as Barr did, and he is the beneficiary of considerable goodwill, which is waning in certain corners but is still apparent in his coverage. One pertinent example: Hatchet Man calls the department’s defense of Trump in the Carroll lawsuit under Barr “flimsy” and “meritless,” but when Garland continued it last month, Honig was far less critical of the decision—writing that Garland was taking an “institutionalist approach to managing the department.” Like many of us, Honig seems to be struggling in real time to reconcile the studiously crafted public image of Garland—the one built on lectures about the rule of law—with the messier reality.

There is no formula to predict how or why someone might prove to be a good attorney general. Prosecutorial experience may help, but you do not have to have been a line prosecutor to be an honest and uncorrupt person.

The business of law enforcement is more political than government lawyers tend to want to admit—both in the sense that politics has a justifiable role in setting law enforcement priorities, and also in the less obvious sense that many decisions require judgments about competing political values because the answers to the underlying legal questions are not actually obvious or determinate. How those values are balanced and prioritized can prove to be the difference between which constituencies get direct access to the department and which do not, and between when the department deviates from its standard practice and when it does not. The sooner we admit this—and the sooner we evaluate nominees on this basis and ask them real questions rather than politically neutered ones—the better.