After decades of exhausting climate change denial, we’re now in the new era of disingenuous corporate environmentalism, all while companies work furiously to delay the demise of the fossil fuel industry. The “net-zero” plans these companies offer are consistently weak and ineffective, but far too often they successfully divert scrutiny away from high-emissions organizations.

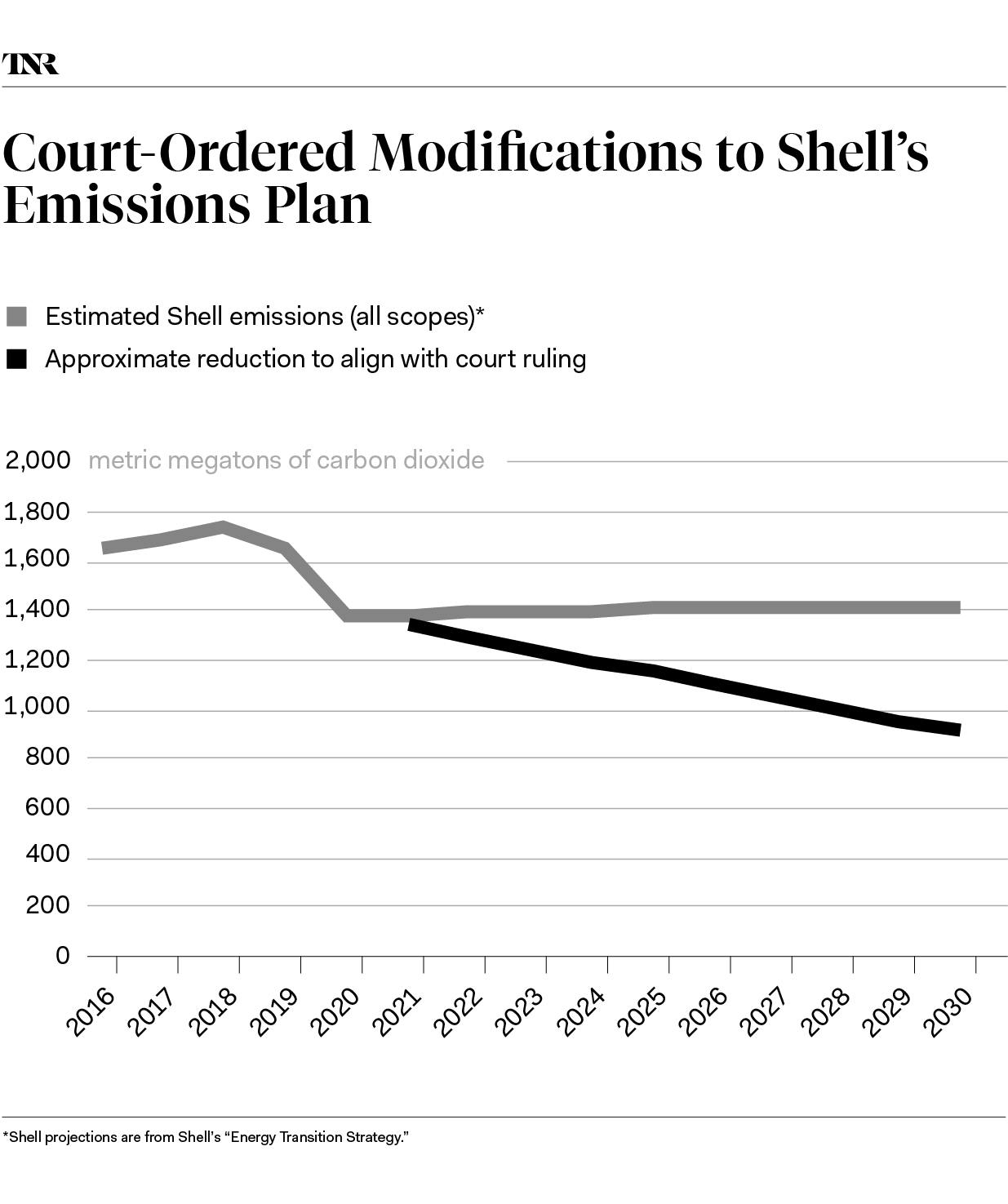

That strategy received a colossal blow this week when a Dutch court ruled that fossil fuel giant Shell is obliged to cut its carbon dioxide emissions by 45 percent by the year 2030 to align with the goals of the Paris climate agreement. The case, brought by a collection of climate activists in 2019, was dismissed in January by Shell’s vice president of strategy and portfolio as a “noisy distraction.” Five months later, that glib hubris has been spectacularly countered.

To understand the significance of Wednesday’s ruling, you have to understand the years of corporate maneuvering that the Dutch court rejected. The privately owned companies that extract, process, and burn fossil fuels, and their complex network of lobby groups, have become adept in recent years at superficial P.R. moves to suggest to the public that they’re taking climate change seriously. Mainstream politicians and nongovernmental organizations, meanwhile, have finally started to admit fossil fuel growth needs to end. Earlier this month, the International Energy Agency published a new report that called for the immediate cessation of the construction of new coal plants and coal mines, and the end of new oil and gas field exploration.

That’s a substantial shift. For some time, the IEA served up narrative defense for the continued expansion of fossil fuel industries. The group’s annual “World Energy Outlook” modeled high-fossil scenarios and underestimated renewable energy’s potential to expand rapidly. Fossil fuel companies then pointed to these scenarios as evidence of the continued need for expansion.

With increasing mainstream acknowledgment of the need to phase out fossil fuels, oil and gas companies are now trying to slow their decline—all while furiously masking that goal with layers and layers of public relations material hyping their green investments and good intentions to stave off the scrutiny of investors, customers, and partners.

Few companies exemplify this better than Shell. The sheer time and effort it put into producing its thicket of exaggerated “climate plans” is stunning. In my own analysis work for the Australian Centre for Corporate Responsibility, a shareholder activist organization, I’ve found that the plans use every trick in the book to put their fossil business on life support while presenting that as if it’s ambitious climate action.

Shell creates emissions targets, but these refer to the “intensity” of its emissions, not the total mass of greenhouse gases it is responsible for. That means it can plonk the sales of renewable energy on top of an unchanged or even rising quantity of fossil fuel sales, and its emissions intensity falls.

Its latest publication, an “energy transition” plan released in April, suggests that Shell is putting its oil and gas business on life support. The company’s oil fields will “naturally” decline at a rate of around 5 percent per year, but Shell is pouring a cool $8 billion into artificially lifting that decline to only 1–2 percent per year. It’s also aggressively expanding its methane business, pinning its hopes on the severely outdated narrative of this gas as a “bridge fuel” for the power sector. A new, industry-wide marketing push labels the stuff as “carbon neutral LNG” (liquefied natural gas), because carbon credits, controversial and certainly not designated for this purpose, are purchased by Shell for the emissions associated with the product. It’s ghastly.

Shell’s expansion into sales of clean electricity, namely from wind and solar, remain a tiny proportion of its total sales of fossil energy. Its current strategy assumes vertigo-inducing rapid growth in tree planting, carbon removal, and carbon capture in the coming years, a key tactic used to justify a fossil-heavy future in so many “net-zero” plans. Shell successfully convinced its investors to vote in favor of this “transition plan,” with a vote last week resulting in 88.74 percent support. While a lower level of support than in votes on other resolutions, it was a substantial amount for a plan that essentially ignores the urgency of the climate crisis.

That brings us to this week’s court decision. Shell’s arguments—used broadly across the industry—were sequentially demolished in the massive document detailing Thursday’s ruling from the District Court in the Hague. The suit, brought by seven climate activist organizations, alleged that Shell’s business model endangers human rights and lives by enabling the burning of fossil fuels, which damage the Earth through the greenhouse effect. The court, very simply, agreed in full, and the ruling applies to the entire company, including its operations outside the Netherlands. Though questions remain about how it will be enforced, it’s significant for several reasons.

First, the court cited the IEA, along with the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, as the global baseline for emissions reductions. Shell, the judge wrote, is responsible for the carbon emissions released when it extracts and refines its products, in addition to those emissions released when its product is used. That’s in contrast to fossil fuel companies’ typical position that emissions are partly the responsibility of the consumers that burn their products. “[Royal Dutch Shell] is free to decide not to make new investments in explorations and fossil fuels, and to change the energy package offered by the Shell group, such as the reduction pathways require,” said the ruling. It could, to put it simply, just stop producing and selling high-emissions products.

It is the legal manifestation of a viral tweet sent in 2019 by climate writer Mary Heglar. “Find out your #carbonfootprint with our new calculator,” U.K. oil and gas company BP shamelessly suggested to consumers on Twitter. “Bitch what’s yours???” Heglar shot back. A new study breaks down the personal carbon footprint of fossil fuel executives relative to their company shareholdings, with Shell CEO Ben van Beurden clocking in at 18,721 metric tons of carbon dioxide equivalent; a bit more than 2,000 times the annual carbon footprint of the average European. “What the executives and directors share in common is a desire to maintain demand for oil and gas, and to defend their company’s social license to operate,” write the study’s authors.

Shell’s company carbon footprint was a monstrous 1,658 metric megatons of CO2 equivalent in 2019. The heart of the ruling is that this is because the company is comprised of people who each chose to continue selling the product that causes the release of that mass of greenhouse gases, and that to remove this harm would entail, simply, choosing not to supply fossil fuels to the world.

The court rejected other extraction industry tropes, too. For some time, companies such as Shell have insisted that the only path to “affordable” and “reliable” power is a deep reliance on fossil fuels, in reference to the United Nation’s Sustainable Development Goals. But the court ruling highlights that these goals are not meant to “detract from the Paris Agreement or to interfere with these goals,” and that these goals “have no bearing on [Royal Dutch Shell’s] reduction obligation.”

One of Shell’s favorite lines is that it will only reduce emissions “in line” with “society.” That, the court deduced, means that Shell reserves the right to “undergo a less rapid energy transition if society were to move slower.” It’s betting its bank balance on a total failure of rapid climate action, and it’s being particularly secretive about it, too. In doing so, the court wrote, Shell “disregards its individual responsibility, which requires [Royal Dutch Shell] to actively effectuate its reduction obligation through the Shell group’s corporate policy.” Shell even argued that to reduce its climate impacts in line with the Paris climate agreement would be too great a financial hit. But that hardly suggests that global warming is consumers’ fault, if the company’s entire business model falls apart under sustainable emissions targets.

The ruling, in other words, was an unprecedented dismantling of Shell’s massive greenwashing exercise. Left unsupervised, the company—like many—defaults to fabricated climate action and industrial protectionism. Shell has promised to appeal, but it’ll have to argue, publicly and explicitly, about why it should be allowed to breach the operational bounds of our biosphere for its personal enrichment.

The Hague’s ruling marks the first time a company has been forced by a court to face the consequences of selling stuff that heats up our home. Unjustified celebration is a constant risk in the climate space, but we can confidently take this moment to look at the big picture—there are fewer places to hide, today, and that is inarguably a very, very good thing.