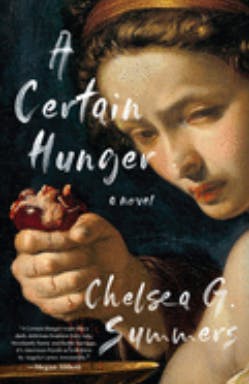

The rendered fat of dead animals may seem like an unlikely aphrodisiac, but the scent adheres to a certain erotic memory for Dorothy Daniels, the narrator of Chelsea G. Summers’s new novel, A Certain Hunger. The book takes the form of an extended monologue about her life of violent crime, as she serves life in prison. When she was a teenager in 1980s Connecticut, Dorothy seduced a fry cook in the front seat of his Impala, having seen him flip burgers and feeling the need to “to lose [herself] in the dead meat grease stink of his skin,” as a “miasma of beef tallow, dirty corn oil, and unwashed man surrounded us.”

It’s a fragrant image, and characteristic of Dorothy, a wry and remorseless raconteur who takes her license to kill from her appreciation for the beauty of it all. A self-described psychopath, Dorothy makes up for what she lacks in conscience with a talent for exulting in the tastes, smells, and lovers that come her way. As the 1980s give way to the 1990s, she tires of fry cooks in low-slung Levi’s, moves to New York City, gets a job as a food critic at a glossy magazine, and somehow or other starts killing and eating men.

Adding to the charmingly improbable notion of a sexy professional journalist turning her boyfriends’ corpses into gourmet meals for one, Summers studs Dorothy’s recollections with scenes of Manhattan indulgence a critic can only dream about today. She lands the food critic job, for example, after shouting at a rich man over “the thudding bass of C + C Music Factory and a sea of upended vodka shots” that “the braised Malpeque in lemongrass crème tasted like a fifteen-year-old boy’s fantasy of cunnilingus.” I wasn’t in New York in the 1990s, but this seems to be the way people used to get jobs as writers: being witty within earshot of someone rich.

Without giving away too much, it’s fair to say that Dorothy is a very discriminating killer who only eats carefully preselected parts of carefully selected victims’ bodies. My favorite of her murders is the tongue she cuts out of an ex’s throat by its root (“each time, digging deeper, angling the knife up and back toward the soft palate, watching the blood ebb like warm cherry cobbler into the Atlantic”) through an incision made low in the throat.

A Certain Hunger is not a horror novel or a thriller but more like a symbolic comedy determined to make the whole “ironic misandry” schtick into something complicated and engaging. Though both rape and revenge feature in the story, it is not a rape-revenge plot. The precision and passion Dorothy bring to murder have a stronger relation to her obsession with food: She has an intense sexual relationship with a kosher butcher, for example, who thrills her with the process of slicing throats and porging the veins—the technical process of stripping the vessels from the flesh. Her need for control in human relationships runs far hotter than her anger.

Though Dorothy keeps her composure ironclad throughout the book, she is human, and her possible motives become clearer as the book goes on. In particular, she purports to be unmoved by the death of her mother, but it’s not long later that she starts wielding blades. Or is the sexual assault Dorothy describes experiencing in Italy as a student the precipitating factor in her homicidal streak? Instead of answers, Dorothy gives us sense-images: “A simple plate of cut tomatoes oozing their sun-warmed guts, drizzled with oil, and sprinkled with flaky diamond-white salt.” Tomato, lover, sentence: all equal sources of pleasure for our hedonist narrator, and all equally effective rebukes to boring questions.

The book’s jacket copy calls Dorothy Daniels “the epicurean lovechild of Elizabeth Báthory and the vampire Lestat, if they were fluent in New York media,” but I much prefer the elevator pitch she mentioned in a blog post once: “Eat, Pray, Love meets American Psycho.” She has plenty to say about women psychopaths like Báthory (her theory is that they exist as abundantly as the men only hide it better), but as a narrator, Dorothy does have more in common with murderer-narrators like Patrick Bateman, Tom Ripley, or Jean-Baptist Grenouille from Patrick Süskind’s influential novel Perfume.

This last is also the story of a lone-wolf killer gifted with an extraordinary sensory palate, which eggs him on to violent frenzy. In the eighteenth-century Paris of his birth, Grenouille basks in the disgusting intensity of the city’s smells the way that Summers recalls the smell of a decades-ago fry cook: “The heat lay leaden upon the graveyard, squeezing its putrefying vapor,” Süskind writes, “a blend of rotting melon and the fetid odor of burnt animal horn, out into the nearby alleys.” Dorothy also experiences flavor with this level of detail, and in both books the collective weight of sensory images slowly creates something like an ethic of murder, posing violence as a creative act with an inevitable relationship to other forms of art—murder as a tribute to beauty.

This is the first novel for Summers, who is, like Dorothy, a striking woman in her fifties with flame-red hair and a taste for translating sensory revelations into language. I came across her writing in the now-defunct magazine of erotica Adult, and it was at a reading for that publication that I once saw her glide past, her sheet of glossy hair reflecting what little light there was in the room, every eyeball swiveling to watch her like iron filings drawn by a magnet. The echoes between Summers and Dorothy aren’t necessarily important—A Certain Hunger is a toothsome morsel regardless of who wrote it—but it is interesting that Summers has pursued the question of sex’s relation to language and food in both her nonfiction writing and, now, a full-length novel. She’s written about her experiences of aging and stripping and beauty for a variety of outlets, including personal blogs. It shouldn’t be the case, of course, but it’s still a rare thing to find a woman over 50 who writes about sex, beauty, and self-image so frankly in the first person.

It’s difficult to joke about killing men or burning books in writing these days, because humorless people on the internet are so eager to take you seriously: I’m sure a handful of readers will find A Certain Hunger insulting to their masculinity, or misread it as a Satanic call to feminists everywhere to spatchcock their husbands. But most readers will find Summers to be a writer in charge of compelling new powers, and the sheer absence of guilt or remorse in Dorothy a refreshing antidote to the anxious moral calculus so popular in much contemporary fiction. A Certain Hunger is a swaggering, audacious debut, and a celebration of all the wet, hot pleasures of human contact.