In the earliest phase of European capitalism, Marx’s old story goes, a significant number of laborers renounced agrarian communities for towns and cities, dissolving the family unit and moving from one place to another. As Christopher Chitty writes in Sexual Hegemony: Statecraft, Sodomy, and Capital in the Rise of the World System, these workers encountered the state of propertylessness for the first time and transformed from husbands of women and the land into people connected by “impersonal market-mediated relations.” In early modern towns and cities full of solitary laborers, and in the Mediterranean ports where sailors flowed through a porous social texture like water, large numbers of men mingled in common lodgings. These towns, where maritime trade and merchant capital had led to new pools of artisanal, servant, and slave labor, “therefore tended to favor homosexuality,” Chitty writes.

This is but one moment from Chitty’s sweeping history of the relationship between sexuality and capital, which seeks to answer a seemingly trollish question: What if there were no such thing as homophobia? Chitty’s not suggesting that violence against gays is some fiction. Instead, he’s pointing out that homophobia tends to be treated as a “timeless force of exclusion,” some inevitable element of human nature, rather than a relatively recent historical behavior. Specifically: behavior brought about by the convulsions of market capitalism. To read Chitty is to experience something like the “galaxy brain” of meme culture, the kind of world-upending feeling one gets from Antonio Gramsci or Silvia Federici, who also use Marxian theory to question the aspects of our social reality that we take for granted.

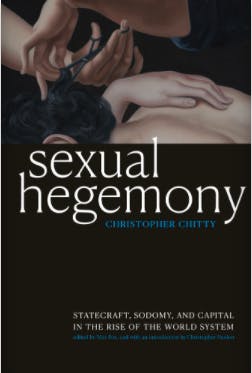

Chitty is not alive to see the publication of these striking ideas. Max Fox, the book’s editor, explains in his foreword that Sexual Hegemony “represents both a precious record and a bitter loss”: Chitty committed suicide in 2015 before he could submit a version of it as his doctoral dissertation. In Fox’s words, he was a “brilliant young scholar and activist” in the University of California Santa Cruz’s History of Consciousness Department. After his death, Chitty’s family and friends gave Fox access to “early drafts of chapters, essays submitted as coursework, notes for further refinement or research,” and so on. The book is structured like a dissertation, though a hair shorter than most. The style is academic but sparklingly clear, if you concentrate, though it’s not what anybody would call skimmable. Fox must get the credit for the polish and sheer rhetorical coherence that Sexual Hegemony boasts as a whole.

Here’s another historical example, Engels-style, from the mid-nineteenth century. In 1841, urinals “towering twelve feet above the street, capped with a round glans-like finial,” popped up along the busiest streets of Paris, sparking a trend in sanitation reform that would soon see public toilets studding all the major capitals of Europe. Britain was in the full bloom of industrialization, and the towns buzzed with young workers. Almost immediately, a new problem emerged, as women—especially middle-class British women—complained that these new conveniences provided them with unwanted glimpses of men’s penises. Middle-class bourgeois outrage spread fast and caused literal walls to be built around men’s public toilets, which, in Chitty’s rather luxurious phrasing, “erotically intensified the experience of urination in public by providing a semiprivate, same-sex urban space.”

At the very same time, forensic medicine in France and Germany “discovered” the psychological definition of homosexuality. British elites suddenly became terribly concerned about deviancy among the nation’s poor, of all genders, and “mobilized forces of social control” to make them behave better—hence the invention of the public urinal, and crackdowns on sex between men. It was a “struggle over the phallus,” instigated by capitalism and animated by conflicts between various combinations of class and gender, one where “the entry and influence of middle-class women into the public sphere is the decisive factor in changing norms of urban policing around public displays of sexuality—namely, prostitution and homosexuality.”

Running through all this, Chitty argues, is a deeper truth that doesn’t quite line up with anything historians have said before: “[S]ocioeconomic progress is directly to blame for a wider basis for sexual repression.” Where markets tremble, sexuality is policed, and wherever there are police, the “deviants” of a society become more visible. From this truth then emerges another, just as the big brain follows the littler brain in the meme: “Thus the massive American economic boom of consumer society following the second World War extended middle-class sexual norms to ever more Americans and led to the most extensive policing of homosexuality in any period of history.”

If we think this way, Chitty writes, we can see how America’s fundamentalist Christian revival and the “free love” radical counterculture of the 1960s were “perhaps two faces of the same spiritual awakening,” paired forces that antagonized and inflamed the other according to a logic dictated by—you guessed it—capital.

If Chitty’s theory of the universe makes intuitive sense to you, then you are not alone. As I read Sexual Hegemony slowly, like a child trying to understand all the big words, it felt obvious: Of course more men would have sex with each other when compelled to live side by side, bereft of the family structures they’d left behind. Of course those sexual dynamics would bear some relationship to markets. Of course all that helps explain the correlation between the mad, intense American postwar boom and the massive postwar fuss called “homophobia,” which grew so powerful we needed scientists to study it.

Chitty’s study could probably only have come out of UCSC’s “HistCon” department, a peculiar institution founded in the 1970s. Among its first appointed professors were the literary theorists Hayden White and James Clifford, who were later joined by Angela Davis and Donna Haraway, among others. Founder of the Black Panthers Huey P. Newton received his Ph.D. in HistCon in 1980, which gives you a flavor of the department’s inclinations.

The chief authority Chitty takes aim at in Sexual Hegemony is Michel Foucault, the theorist whose work made HistCon possible. His History of Sexuality had an explosive effect on the twentieth-century postwar intellectual scene, because he had figured out a way to speak about sex and capitalist development in the same breath. Among its sledgehammer ideas is that the new medical science of the nineteenth century produced the “homosexual” by defining it. For Foucault, repressive forces don’t just push marginalized communities to the edges of society but cause them to exist.

The problem with this argument, Chitty thinks, is that it frames oppressed communities as totally passive, as well as suggesting that there is some unique quality to modern gay sex that it never had before. Foucault’s argument doesn’t much account for what was happening before modern science reached its position of authority. Surely there were changes going on in the way people formed sexual relationships as capitalism marched across the globe, Chitty insists, that we can read about and observe in action?

It matters what we forget and what we remember. Perhaps the saddest moment in the book comes toward its end, when Chitty notes that the “boldest propositions have tended to be advanced at the margins of gay history, buried in endnotes or writing not published in the historian’s lifetime.” It’s certainly true here. Lovingly, he frames Sexual Hegemony as a tribute to the unremembered working-class gays of centuries past, who have not been part of the inherently elitist microscope of queer literature. “The oblivion faced by working-class homosexuals was an oblivion of historical memory,” Chitty writes; “by contrast, their elite counterparts left behind a labyrinthine wardrobe of tortured interiority, self-involvement, and coded references in which subsequent generations of queer readers have wandered.”

When we do history this way, Chitty argues, we can sidestep the problem of trying to guess whether queers from history were “authentically gay” or just responding to the pressures of poverty or class hierarchy. We think of modern queer sexuality as defined by the individual’s freedom: a tenet we can see most clearly in the importance we place on the concept of consent. When we read about a poor teenaged boy having sex with rich older men in early modern Venice, our ordinary language of consent just doesn’t apply. But this binary between “real” and “situational” gayness is a false one, Chitty thinks. All sexual encounters, whether present-day or historical, are subject to the contingencies of time and place and power dynamics.

The story behind Chris Chitty’s book also moved me, for a reason the author himself specified. Gay people, he writes, have a particular desire to understand themselves as part of history, for the very reason that we don’t see ourselves in the past. This makes the “homosexual desire for history … itself historical,” he writes, a phenomenon that always leads us to feeling out of place, cut off from solidarity. We have an uncertain kinship with the misunderstood and the dead, who have also lost their place in the world. The desire for history that runs so hot through queers today is also a desire to recognize and be recognized. Both a labor of love and a collaboration across the frontier of death, Sexual Hegemony is one of that desire’s most uniquely affecting expressions.