A lot of people found Mecklenburgh Square by accident. T.S. Eliot, who taught at nearby Birkbeck College, described it, on discovering it in 1917, as “a most beautiful, dilapidated old square, which I had never heard of before.” And D.H. Lawrence, who lodged in one of its many low-cost boarding houses in the 1910s, called it the “dark, bristling heart of London.” A noted residence of Fabians, suffragettes, radical thinkers, Christian socialists, in the early twentieth century it was home to practitioners of open marriage (such as the poet H.D. and her husband, Richard Aldington) and same-sex couples like the elderly classics scholar, Jane Harrison, and her 37-years-younger former student, Hope Mirrlees. (Harrison and Mirrlees’s longtime home together was characterized by their neighbor, Virginia Woolf, as “all Sapphism.”)

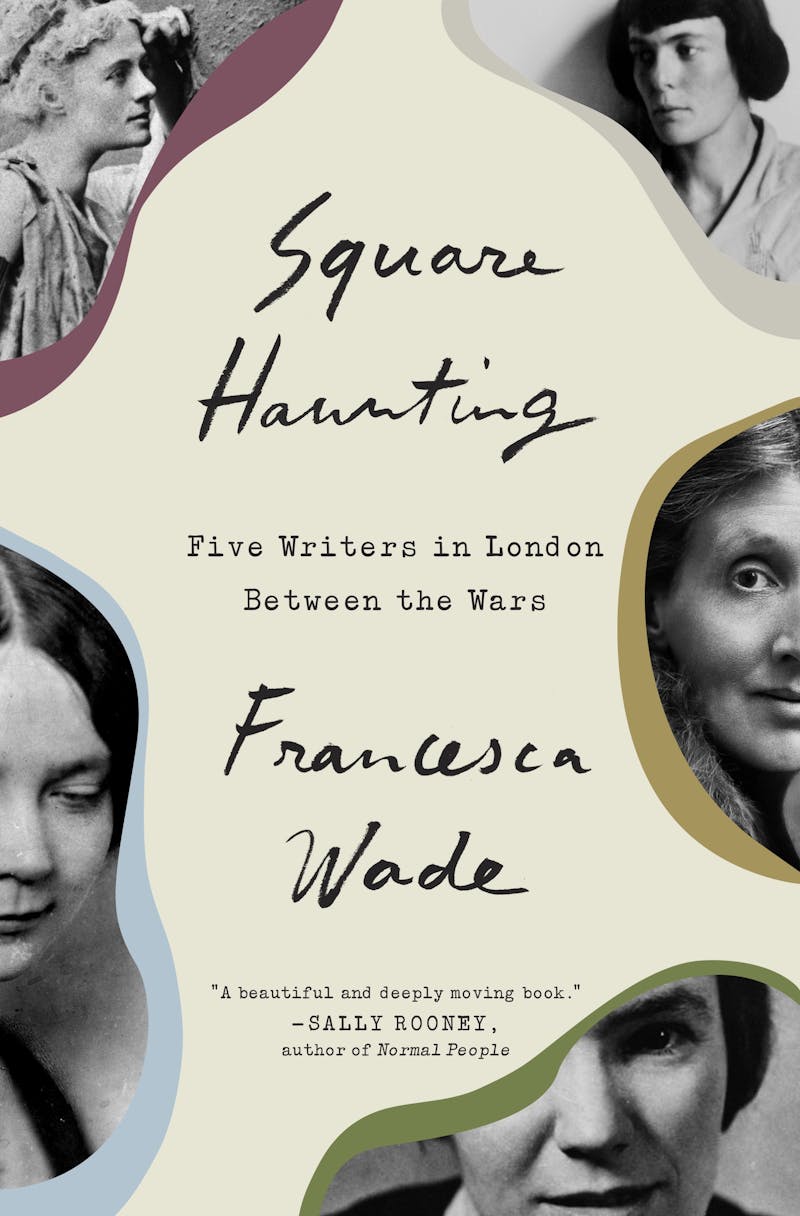

As Francesca Wade writes in Square Haunting: Five Writers in London Between the Wars, Mecklenburgh was a “radical address” that drew artists, writers, poets, and intellectuals, many of them women. Close to the British Museum Reading Room, and secluded from much of the clatter and stink of industrial London, it provided the sort of “furnished rooms” that were variously described as “second-rate boarding houses” or “high-class service flatlets.” (“I read and write at the British Museum,” wrote Dorothy L. Sayers in her early days of work and research, “and have my meals and go to bed.”) And since women of the time weren’t entirely well treated by the universities and libraries (which were either resistant or actively opposed to the idea of women researchers and teachers), Mecklenburgh Square gave them a space to work and study.

Between the world wars, it was a place, Wade writes, “where a new kind of living seemed possible, and where radical thought might flourish amid a political atmosphere founded on a zeal for change.” While Virginia Woolf advocated that women find a “room of one’s own” in which to work—and Harrison urged women to move from the “drawing room” into the “inviolate” territory of “the study”—that was much easier said than done, especially for budget-conscious young women just out of university. As both H.D. and Sayers learned (by a coincidence, they rented the same largeish single room several years apart), in the more affordable rentals of central London, the “study” often was the “drawing room.” And the kitchen and bedroom as well.

The residents of Mecklenburgh Square didn’t comprise a “movement” so much as a loose agglomeration of individuals seeking a space in which to establish their own private geographies. The five women profiled by Wade pursued widely different intellectual careers in similar surroundings, and included an imagist editor and poet just embarking on her career (H.D.), a well-established novelist and essayist coming to the end of her own (Woolf), an errant young Oxford graduate who eventually fled academia to write comic drawing-room murder mysteries (Sayers), a linguist and classical scholar (Harrison), and a medieval historian (Eileen Power) who helped establish the London School of Economics. Many residents saw themselves as “an alternative Bloomsbury set … focused not on abstract discussions of art or philosophy but on practical policies designed to change society for the better.” (Power’s friend and colleague, R.H. Tawney, once referred to the Bloomsbury set as “a mental disease.”) Woolf didn’t stay long, moving away shortly after the German bombs hit her home in 1940.

Never could a neighborhood be better described as liminal. The spaces of Mecklenburgh Square were between many different territories—between wars, ideas of gender, moral codes, and London’s wide economic extremes—with the City’s banks close by in one direction, and Bloomsbury’s “lefties” in another. “If you lived here,” Margery Allingham wrote in 1938, “you were either going up or coming down.”

When Hilda Doolittle first moved to the Square from her middle-class life as a Bryn Mawr graduate, Parisian nightclubber, and former lover and fellow poetic traveler of Ezra Pound, she felt she was falling through the cracks. But to an adventurous spirit like Dorothy L. Sayers, Mecklenburgh Square felt like discovering the life she had been looking for before she even knew it existed. When Sayers first visited the room where she would live, study, and conceive her greatest fictional creations—Lord Peter Wimsey and the wildly yearning Harriet Vane—she expressed the sort of “rapture” that her father, a Christian rector in Cambridgeshire, might have wished upon her:

a lovely Georgian room, with three great windows … and a balcony looking onto the square. There is an open fireplace, and the last tenant has thoughtfully left some coal behind.… The landlady is a curious, eccentric-looking person with short hair … and thoroughly understands that one wants to be quite independent. That is really all I want—to be left alone.

Mecklenburgh Square’s boardinghouses and gardens granted a rare form of freedom to women seeking to live “experimental” lives. It allowed them in, but the world outside didn’t seem to keep a close eye on them once they got there. Despite her Christian upbringing, Sayers not only worked, wrote, and studied productively while “happily unmarried” there, but was passionate with several married and unmarried men—at least two of whom (including D.H. Lawrence) had been involved with her flat’s predecessor, H.D. Sayers even managed to conceive a child and, without ever informing her parents, secretly give birth while keeping her day job and writing her second Lord Peter Wimsey novel (Clouds of Witness). As Sayers learned better than anyone, Mecklenburgh Square didn’t provide fancy digs, but it did provide enough free space and privacy for imagining fancy digs into existence. “When I was dissatisfied with my single furnished room,” she later wrote,

I took a luxurious flat for [Lord Peter] in Piccadilly. When my cheap rug got a hole in it, I ordered him an Aubusson carpet. When I had no money to pay my bus fare, I presented him with a Daimler double-six, upholstered in a style of sober magnificence, and when I felt dull I let him drive it. I can heartily recommend this inexpensive way of furnishing to all who are discontented with their incomes. It relieves the mind and does no harm to anybody.

Like Lord Peter, Sayers never abandoned her Christian faith; she just developed a strong dose of sympathy for Christians who engaged in what might be considered un-Christian behavior. (Such as, say, murder.)

Even when the Square’s various between-war residents didn’t know one another, they seemed to fuel one another by proximity and juxtaposition—walking the same streets, frequenting the same parks and benches, and sidling through the same busy byways to Bloomsbury, Holborn, and King’s Cross. Sure, a “room of one’s own” is important, even necessary, in order to imagine a way out of the many mindless restrictions and boring occupations that the world imposes, but enjoying free access to a common, multitudinous public world helps us make decisions about who we want to be when we return to those rooms. Most people have never “felt passionately towards a lead pencil,” Woolf wrote in her essay “Street Haunting,” but sending yourself on an expedition through London in search of one allows you to “shed the self our friends know us by and become part of that vast republican army of anonymous trampers, whose society is so agreeable after the solitude of one’s own rooms.” It’s nice to know who you are. But it’s sometimes equally nice to forget who you are altogether.

There is something anonymous about the approach Wade takes to these many interesting and significant women: While she provides a clear sense of when they each lived in Mecklenburgh Square, she often relies on speculation, or even comes up against the need for facts that aren’t available. For while all five women were important actors in London’s intellectual and social life, they didn’t (with the obvious exception of Woolf and maybe Sayers) leave behind the same mass of recorded material as their male contemporaries, such as Eliot, Lawrence, and Bertrand Russell. The surviving families and partners of H.D., Jane Harrison, and Eileen Power destroyed many of their papers after they died, and it’s fair to assume that most research libraries weren’t astute enough to collect the papers that did come available. Wade admits to encountering many “odd gaps in the record.”

It’s certainly unfair. Eileen Power was a powerful influence in the development of the London School of Economics and in medieval research. H.D. is now recognized as one of the period’s most significant imagist poets and editors. Jane Harrison’s arguments about how ancient cultures wrote female gods out of their religions influenced T.S. Eliot’s The Waste Land. At the same time, Harrison’s partner, Hope Mirrlees, wrote possibly the most significant long modernist poem of the 1920s to rival Eliot’s. It was called Paris: It is finally being reissued in paperback by Faber at the end of this year, and it is everything The Waste Land isn’t—funny, jazzy, optimistic.

Mirrlees’s unfairly forgotten fantasy novel, Lud-in-the-Mist (1926), lay hidden away on library shelves for decades before its commercial rediscovery in the early 1970s by Lin Carter. It envisions an imaginary country called Dorimare that resembles the worst aspects of Victorian England, controlled by legal-bound lawyers and provincial farmers who feel threatened by the existence of a “fairy land” that lies north beyond the Debatable Hills. And despite a ruthless trade embargo, the fairy influences keep filtering over the border in the form of succulent fruit, hallucinogenic dreams, and wild, unlicensed, sensual behavior. Worst of all, it distracts the sternly supervised young people, who should be doing better things than rushing madly off in search of unproductive fairy songs.

Mirrlees never wrote so well again. But then the readerly culture that embraced her male contemporaries—such as Lord Dunsany and James Branch Cabell—didn’t really grant her much attention, either. When her partner, Jane Harrison, died in 1928, she canceled the contract for her next novel, wasted several years failing to write a biography of her longtime friend, converted to Catholicism, and moved to South Africa. Of all the famous residents that Wade describes in this book, Mirrlees is perhaps the only one whose career seems to have ended while living in Mecklenburgh Square.

The haven for artists that Wade writes about has not survived. After the German bombs found Mecklenburgh Square in 1940—just as the reverberations of the zeppelin raids had shaken the shelves in H.D.’s flat two decades previously—the neighborhood was largely evacuated. Woolf, the area’s last famous resident, moved away, and in 1941 she took her own life. And while much of the original Georgian architecture survived the German bombs, many of the original homes have been subdivided into million-dollar flats. They are today no longer the sort of affordable spaces required by independent poets, artists, and scholars. Even the beautifully overgrown gardens, established on the Foundling Estate in the eighteenth century, are now fenced and gated, with keys distributed only to those wealthy enough to afford them.

One thing about Mecklenburgh Square has never changed. It is still a delightfully surprising place to discover when rambling through London, especially when you don’t know where you’re going and are not in any hurry to get there. And after you leave, you almost certainly want to find your way back again. Years after leaving 44 Mecklenburgh Square, H.D. often found herself trying to find a way back—both through her psychoanalytical sessions with Sigmund Freud in Vienna in 1934 and, toward the end of her life, with the publication of a roman à clef, Bid Me to Live (1960), based on her London years with Lawrence, Pound, and Aldington. Perhaps this is because the life we live in our best cities often involves a simultaneous act of remembering and forgetting, an opportunity both to lose ourselves among tides of other people and to find ourselves again. As Sayers wrote in Unnatural Death (1927):

To the person who has anything to conceal—to the person who wants to lose his identity as one leaf among the leaves of a forest—to the person who asks no more than to pass by and be forgotten, there is one name above others which promises a haven of safety and oblivion. London.… Where strangers are friendly and friends are casual … all-enfolding London.