Last month’s Democratic primaries in New York likely made history—for all of American politics. Mondaire Jones won in the 17th Congressional District, which includes Rockland County and parts of Westchester County, while Ritchie Torres won in the 15th Congressional District, in the Bronx. As both districts are deep blue, Jones and Torres will almost certainly become the first openly gay Black and Black-Latinx members, respectively, ever to serve in the U.S. Congress. But their victories aren’t just symbolically significant: They also seriously challenge the myth that Black voters are reluctant to support LGBTQ candidates. According to a survey conducted just before primary day by Data for Progress, Torres had higher support among African Americans than non-Black voters. (No such data exists on Jones voters.)

Black voters have long been depicted as hostile to LGBTQ rights, including same-sex marriage. Last fall, a leaked memo from Pete Buttigieg’s presidential campaign, based on internal focus groups, worried that “being gay was a barrier” for some Black voters in South Carolina. Asked on CNN whether Buttigieg’s sexual orientation would be a problem, South Carolina Representative James E. Clyburn, who is Black, said, “I’m not going to sit here and tell you otherwise, because I think everybody knows that’s an issue. But I’m saying it’s an issue not the way it used to be.” David Axlerod, the chief strategist for Barack Obama’s presidential campaigns, warned that Buttigieg’s sexual orientation was “a real issue for him [because there] has been historical resistance within elements of the African-American community to homosexuality.”

But our research shows that these concerns are unjustified and unfair. In fact, Black voters are now more likely to support gay candidates and other minority candidates than non-Black voters. This is partly because gay candidates in the United States tend to be Democrats, and African Americans remain incredibly loyal to the party, regardless of the candidate’s identity. But there is more to it than that.

This past spring, we surveyed a nationally representative sample of over 6,000 likely American voters. We asked respondents whether they would vote for Donald Trump or Buttigieg, if the latter were to become the Democratic nominee. Black voters overwhelmingly supported Buttigieg over Trump, 70 versus 12 percent, while white voters narrowly backed Trump, 46–42 percent. Even when we highlighted Buttigieg’s sexual orientation, displaying a picture of the candidate kissing his husband, Chasten, on stage, Black voters remained substantially more supportive of him versus Trump, 61 to 11 percent, versus 40–48 among whites.

There are, however, substantial variations within the Black community. When Buttigieg was presented as a proudly gay man, he lost a third of his vote among Black men, as almost all switched to undecided. In contrast, Black women supported Buttigieg over Trump by over 70 percent regardless of whether he was presented in a neutral way or as proudly gay. Black voters under 35 supported Buttigieg over Trump by massive margins (75–11), and even more so when his sexual orientation was accentuated (78–3). Older Black voters were far less enthusiastic supporters of Buttigieg (57–17, with 26 percent undecided) and were thrown into a quandary when Buttigieg was presented as proudly gay (31–15, with 54 percent undecided).

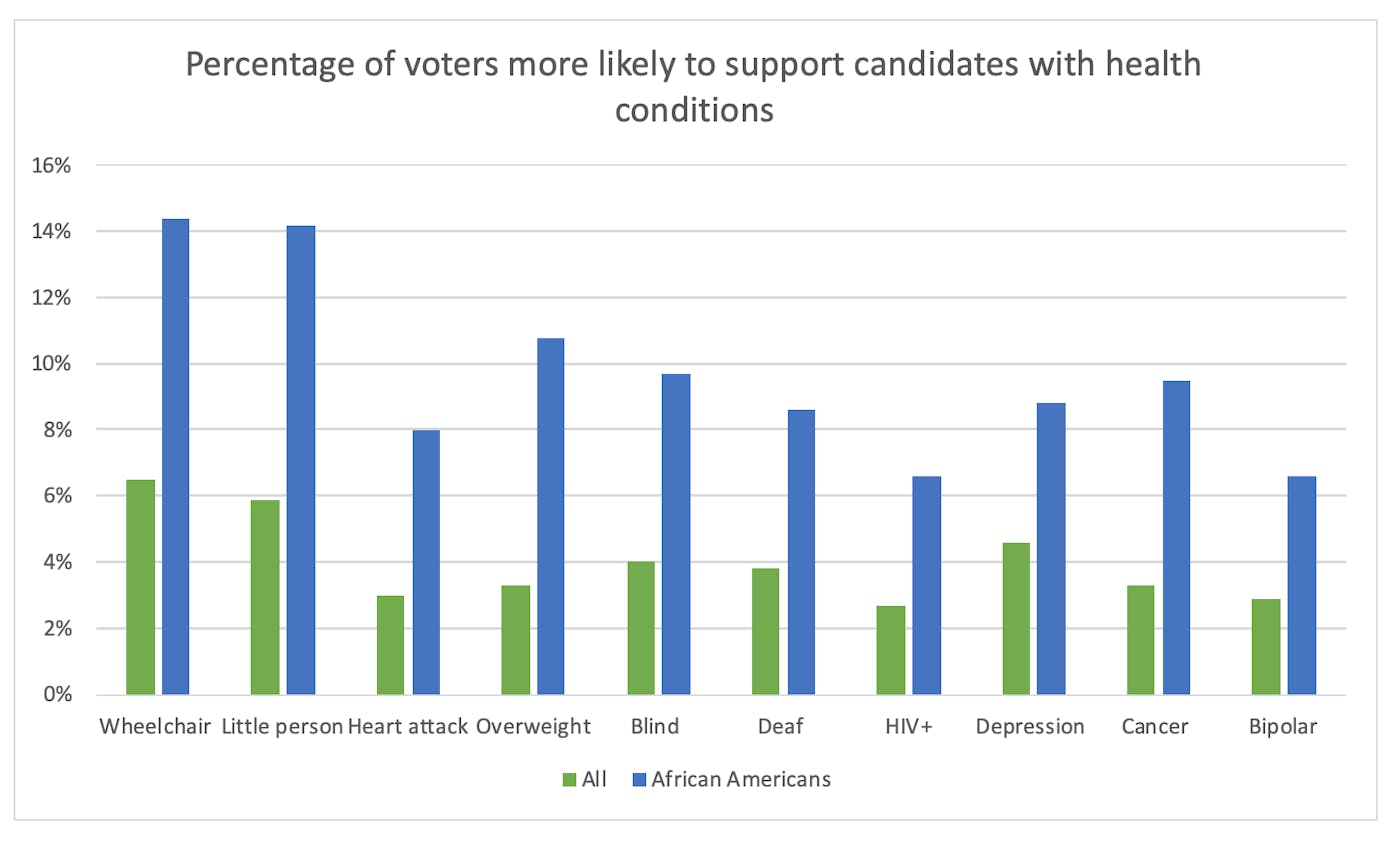

African Americans show greater support than white voters for other minority candidates, above and beyond party ID. In our survey, we also investigated the likelihood of voters to support candidates running for Congress with the following conditions: being overweight with diabetes; having experienced a heart attack, cancer, HIV, depression, bipolar disorder; being in a wheelchair; being blind or visually impaired; being deaf; and being a little person. Black voters said in significantly higher numbers than all other groups that they were more or much more likely to vote for a candidate knowing that the candidate had a health condition or disability.

Such support may be due in part to familiarity, as Black Americans are more likely to be overweight, have diabetes, experience heart attacks, die from cancer, have depression, use a wheelchair, be blind, and be HIV-postive, than the general population. More recently, African Americans have been disproportionately impacted by Covid-19. There is overwhelming evidence that African Americans are much more likely to be hospitalized and die from the coronavirus than whites.

Black Americans, however, are not more likely to have a bipolar disorder or to be—or be related to—little people. African Americans are also much less likely to be deaf than the general population. This suggests that their higher levels of likelihood of voting for candidates with these conditions is partly the result of empathy rather than direct experience. As members of a historically disadvantaged and oppressed group, they can relate to the conditions of those who have been unfairly treated, even if they belong to a different group. As a result, they are more likely to support members of other groups who have faced discrimination.

In recent months, the coronavirus crisis and growing outrage over racist policing have highlighted the violence and discrimination faced by Black people in America. Support for the Black Lives Matter movement has never been so high, as hundreds of thousands of white people have joined anti-racism marches across the country, and books about racism and white nationalism have climbed bestseller lists. White people are slowly realizing how racism is a tumor at the heart of America and are showing greater empathy toward African Americans. But it will require much more progress to close the yawning empathy gap between Black and white voters.