There are some records that sound as if their creators were hit over the head, forgot how to put together a song, then had to rebuild the whole thing from scratch. Think of Van Morrison’s mad originality on Astral Weeks, for example—the way he mixes styles like a person’s mind mixes memories, jazz and classical and Irish forms intertwining. It sounds like something half-remembered from a dream: familiar, although utterly new.

Fiona Apple’s fifth album, Fetch the Bolt Cutters, is one of those records. Until recently, Apple has been identified with a very specific celebrity type—filed by Wikipedia under “female American alternative singer-songwriter.” We hear her name and imagine a pale, beautiful woman scowling into a piano, because that image was seared on the television during the heyday of Apple’s celebrity in the late 1990s. The stereotype of “woman who is sensitive and plays the piano” associates Apple most obviously with Tori Amos and Regina Spektor but also with Nina Simone and Joni Mitchell. It’s a legacy of luminous genius, but also a narrow and slightly depressing one.

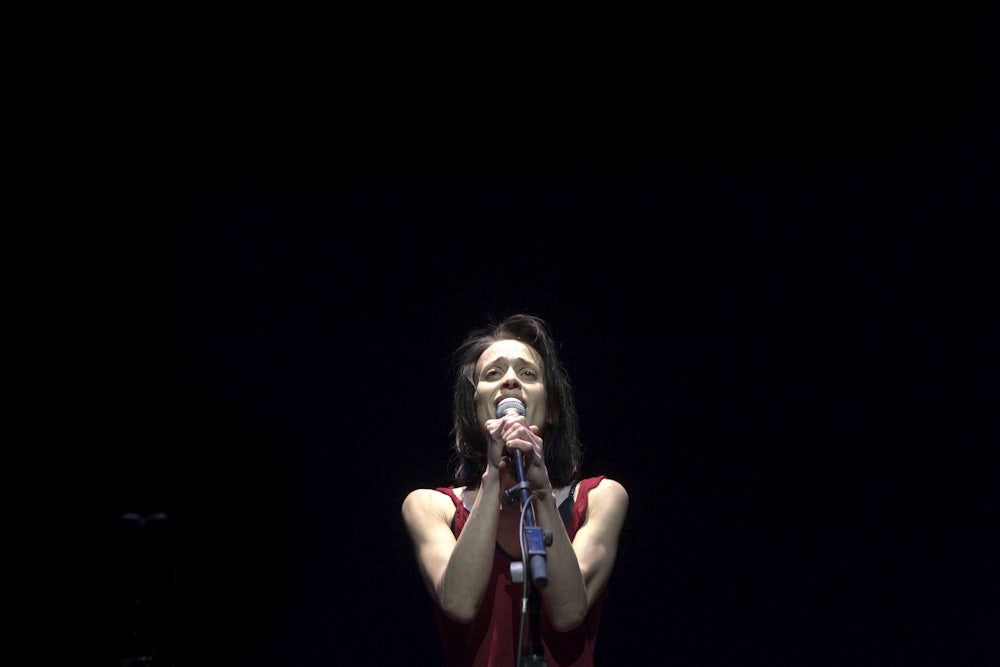

Apple first rose to fame as a troubadour of sad songs gilded with rage, her voice burning with emotion. Songs like “Criminal” and “Paper Bag” were hard to forget once heard. That initial burst of success took place during the adolescence of people who are now in their thirties. For many young girls, Apple’s music was a catalyst to self-actualization, and her albums are cornerstones for a micro-generational group identity.

That kind of legacy can crush an artist, especially one so young as Apple, who was 19 when her first album, Tidal, came out in 1996. For a while, it seemed as though it may have: Apple is reclusive, and she has been out of the spotlight since 2012’s The Idler Wheel. But in preparation for her new album, she has crept back into the public eye via carefully handpicked media appearances, including multiple interviews to Vulture and a long and intimate portrait by Emily Nussbaum in a March issue of The New Yorker.

That profile told of a quiet life, lived inside her California home, with dogs and a friend and the ongoing mission to rebuild her approach to music from the ground up. She used the house itself as a percussion instrument, at one stage playing her dead dog’s bones—a primal and tender transformation of grief into sound. As she got looser and more improvisatory in her approach, Apple stopped caring about making polished tunes. She had spent enough time in the studio waiting for her moment to sing.

The result is, like Astral Weeks, a jazz-infused renovation of her own style, with lots of sweetness in the bass. Highlights include the opening track, “I Want You to Love Me,” titled like one of Apple’s old self-loathing ballads (“On the Bound,” say) but free from abjection. She pulls off some top-grade blue-eyed-soul roaring on this song and on a few others, scraping new textures into her voice. There are flavors of Paul McCartney, Van Morrison, and even Tim Buckley on this record.

The song “Fetch the Bolt Cutters” contains background dog barks, backup vocals by Cara Delevingne, some odd clattering sounds, and other happy accidents. But the real changes are at a deeper level. Put simply, this is just much bigger music.

The title track wasn’t originally going to be on the album, but it’s the most emblematic of Apple’s new direction and a standout moment on the record. It’s a jazzy number, held together by soft percussion, bass, and vibraphone (or something that sounds like a vibraphone—I wouldn’t be surprised if Apple has been tapping a magical seashell or something). She speaks the verses as much as she sings them, in the rhythmic, coffee-shop-poet manner of Tom Waits or Bob Dylan, leaning stress into odd syllables (“I’m ashamed of what they did to me / what I let get done”). The chorus is a soft shuffle of melody, repetitive and pretty as a song by The Books.

Although there is plenty of piano on Fetch the Bolt Cutters, the record is much more wide-ranging musically than Apple’s previous work. On the track “For Her,” complicated rhythms layer with vocal harmonies to create an avant-garde sound reminiscent of Animal Collective (their album Merryweather Post Pavilion falls into that “blow to the head” category, too). That just makes it the more delicious when the old Fiona roars back with a white-hot lyric. To the tune, at first, of the Singin’ in the Rain song: “Good mornin’, good mornin’! / You raped me in the same bed your daughter was born in.”

All the tension hisses out on the fun song “Ladies.” Apple sing-speaks the word over and over again like a compère trying to get people to sit down for dinner at a wedding, but with the louche confidence of Lou Reed singing “Goodnight Ladies” to a room full of groupies. More thrills await inside the track “Under the Table,” about a blowhard boyfriend and his annoying friends, which recalls a certain immortal sentence from Nussbaum’s March profile: “Every addict should just get locked in a private movie theatre with [Quentin Tarantino] and [Apple’s ex, Paul Thomas Anderson] on coke, and they’ll never want to do it again.” It’s a broadening of emotional range.

For better or worse, according to your taste, elements of the old Apple remain. Plenty of fans go wild for it, but if you’ve never enjoyed the vaudevillian side of her music, then skip the songs “Shameika” and “Rack of His.” They’re not bad, not at all; it’s just that Apple’s tendency to decorate her verses with what I can only call theatrical circus piano recalls indie music’s regrettable cabaret phase, typified by the Dresden Dolls. None of that is Apple’s fault—call it the Amanda Palmer traumatic effect—but some of us will never get past it.

A note on the title. “Fetch the bolt cutters” is a line spoken by detective Stella Gibson (Gillian Anderson) on the crime drama The Fall. After a season doing battle with sexist and corrupt colleagues, the glistening Gibson has whittled down the distance between her and the misogynist serial killer to nothing. Anderson plays Gibson like a woman made of steel underneath her silk blouses, and the line encapsulates the paradox at the heart of her character. She has great power, but she wields it to set other women free.

Talking to Vulture, Apple recently said that the message of the record is “just: Fetch the fucking bolt cutters and get yourself out of the situation that you’re in—whatever it is that you don’t like.” Whatever chains once held Fiona Apple have long melted into air and set her loose on a new phase of her creative career. We are trapped indoors, wilting: Fetch the Bolt Cutters is a breeze through an open window.