A week before last Thanksgiving, a group of Republican attorneys gathered at the tony Madison Club a few blocks from the Wisconsin State Capitol to learn what they could do to help reelect President Trump. Established in 1909, the club has hosted Presidents Teddy Roosevelt, Bill Clinton, and Barack Obama, as well as the Dalai Lama.

The November gathering was organized by the Republican National Lawyers Association (RNLA), which, despite its relatively low profile, has worked for decades to give Republican candidates a crucial edge in national elections. The group has developed a network of influential conservative lawyers pushing for tighter voting rules, and it recruits volunteers to provide legal services on behalf of the GOP at the polls and courthouses on Election Day. Among the RNLA’s past members are the Trump-appointed Supreme Court Justice Neil Gorsuch, the former Trump White House counsel Don McGahn, and Hans von Spakovsky, a former Republican appointee to the Federal Election Commission who is now a leading figure in the right-wing push to create barriers to voting. Another RNLA alum is Virginia Representative Bob Goodlatte, who as chair of the House Judiciary Committee bottled up legislation to restore the Voting Rights Act to full strength after it was gravely weakened by a 2013 Supreme Court ruling, Shelby County v. Holder, written by Chief Justice John Roberts—himself a former RNLA member.

Last fall’s confab—which came to public attention thanks to a recording of the proceedings leaked by the Democratic group American Bridge PAC—kicked off with brief remarks from Scott Fitzgerald, the leader of the Wisconsin Senate. Over the last decade, Fitzgerald has played a key role in pushing through a host of measures—voter ID and other restrictive voting laws, gerrymandered election maps, and legislation weakening campaign finance protections—that together have badly undermined the state’s democracy. At the Madison Club, Fitzgerald celebrated the Republicans’ recent success in killing off Wisconsin’s independent, nonpartisan, and widely respected election commission and replacing it with a panel that can more easily be controlled by lawmakers.

After Fitzgerald spoke, the RNLA heard from Justin Clark, a top strategist and lawyer for Trump’s 2020 reelection campaign. “We’re either going to win Wisconsin and win the election, or lose Wisconsin and lose the election,” Clark declared at the outset, setting out the stakes. Then he explained why he was optimistic. “First and foremost: The consent decree is gone,” he said, calling it a “huge, huge, huge, huge, deal.”

Clark was referring to a court-enforced agreement, drawn up in 1982 in response to a federal lawsuit brought in New Jersey after what he delicately called “shenanigans” committed by GOP campaign operatives. For decades, the agreement barred the Republican National Committee (RNC) from conducting “ballot security” activities—essentially, efforts to challenge voters’ eligibility at the polls or in any other way to prevent or deter them from casting a ballot. In 2018, a federal judge ended the ban, finding it was no longer needed. That means that this November will see the first presidential election without it since Jimmy Carter was in the White House. Voter protection groups are already bracing for potential trouble at the polls.

It’s not that Republicans will have a totally free hand, of course—blatant voter intimidation, as well as racial discrimination in voting, are still illegal. But Clark told his audience that the lifting of the decree would allow the RNC to coordinate all its Election Day activities with the Trump campaign, state parties, and the House and Senate Republican campaign arms. Clark went on to describe a multimillion-dollar RNC-funded effort to flood the polls and courthouses with Republican activists and lawyers this November. The initiative, he promised, would represent “a much bigger program, a much more aggressive program, and a much better funded program” than any similar GOP effort in other recent presidential cycles. He added: “This is all a result of us being able to budget and coordinate directly with the RNC.” Some swing-state Republicans may already be taking advantage of the change. Florida’s GOP-led legislature is advancing a bill to allow Election Day poll watchers to monitor any precinct in the state; currently, they have to live in the precincts they surveil.

And of course, the newly unleashed RNC won’t be working alongside an ordinary GOP standard-bearer. Instead, it will team up with a candidate who, ahead of his 2016 election and throughout his first term in office, has led an unprecedented and unhinged crusade against alleged election fraud, and has repeatedly urged his backers to act as a vigilante-style anti–voter-fraud police force. Now, in his remarks before the RNLA, Clark was making it clear that, without the consent decree in force any longer, Trump’s paranoid obsession with thwarting the workings of democracy can form a critical component of the GOP’s 2020 electoral playbook.

“Every time we’re in with [Trump], he asks, ‘What are we doing about voter fraud? What are we doing about voter fraud?’” Clark told the lawyers. “Which is great for a guy who’s looking for budget approval on stuff, because I can say, ‘Hey, the president really wants it.’ But the point is, he’s committed to this, he believes in it, and he’ll do whatever it takes to make sure it’s successful.”

When not speaking privately to party activists and lawyers, RNC officials put a somewhat different spin on what the end of the consent decree means. “Lifting of the consent decree allows the RNC to play by the same rules as Democrats,” Mandi Merritt, a spokeswoman for the RNC, told The New Republic in a statement. “Now the RNC can work more closely with state parties and campaigns to do what we do best—ensure that more people vote through our unmatched field program.”

Indeed, Clark did tell the lawyers assembled in Madison about plans to turn out the state’s Republican voters more effectively in 2020. But his presentation also suggested that boosting turnout in GOP areas will be only one side of the coin. The consent decree’s own fraught history gives an all-too-vivid picture of what the other side might look like.

Intimidating minority voters at the polls has been a part of the GOP’s election strategy for even longer than nonwhite voters have reliably been supporting Democrats. And by the 1980s, Republicans had perfected the scheme. Clark called the activities that led to the original 1982 decree “shenanigans,” as if talking about a high school prank. In fact, the RNC carried out a coordinated political plot to systematically disenfranchise nonwhite voters.

In the early 1980s, the backlash to the gains of the civil rights era was in full swing. In 1980, Ronald Reagan, who had built a national following decrying “welfare queens” and the “strapping young buck” who buys T-bone steaks with food stamps, was elected president.

Then, as now, voting was at the heart of conservatives’ fears. The dynamic that today governs much of the battle over access to the ballot—that Republicans do better when turnout is lower, especially among minorities and other marginalized groups—was just becoming clear. “I don’t want everybody to vote,” Paul Weyrich, the legendary conservative activist and co-founder of the Heritage Foundation, told a religious right gathering in Dallas during the 1980 campaign. “As a matter of fact, our leverage in the elections quite candidly goes up as the voting populace goes down.” Two years later, a young John Roberts would send a memo to his boss at the Reagan Justice Department outlining a sophisticated legal strategy to dramatically narrow the scope of the Voting Rights Act.

Around the same time, a much cruder scheme landed Republicans in hot water. In the lead-up to a 1981 race for governor of New Jersey, top RNC officials launched an effort they called the National Ballot Security Task Force. According to a complaint later filed by Democrats in U.S. District Court, the task force first used voter registration lists to send letters to voters in minority-heavy districts. The envelopes requested that undeliverable letters not be forwarded but instead returned to sender. The task force got back more than 45,000 letters—about 4 percent of the state’s total nonwhite population at the time. Then, less than two weeks before the election, they went to election officials throughout New Jersey and urged them to purge these voters from the rolls—a voter suppression tactic known as “caging.” When the election officials investigated, they found that the task force had used outdated voter registration lists —and that, indeed, most of the voters under challenge by the RNC either had already been removed from the voting rolls or had transferred their registration to a new address.

The Republicans were undaunted. In a transparent effort to spread fear about voting, RNC officials announced to the media about a week before the election that they planned to challenge ballots cast by these voters. Then, according to the complaint, the task force, working with local police agencies, hired deputy sheriffs and police officers to patrol the polls on Election Day in urban neighborhoods with large minority populations. These self-styled poll watchers were armed with revolvers; they also sported two-way radios and armbands reading “National Ballot Security Task Force” (even though no such organization existed as anything other than a voter-intimidation arm of the RNC). The task force’s director, a Washington-based RNC employee, was made a deputy sheriff as part of the scheme.

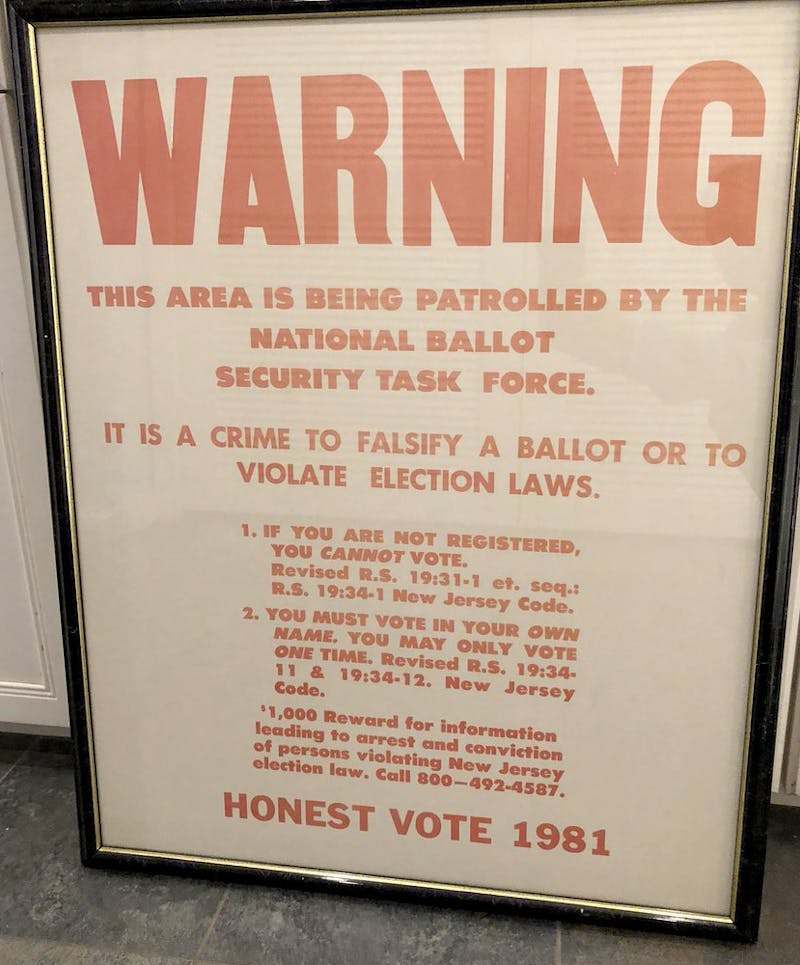

Once the poll monitors had set up shop, they soon began, in the language of the complaint, “disrupting the operations of polling places, harassing poll workers, stopping and questioning prospective voters, refusing to permit prospective voters to enter the polling places, ripping down signs of one of the candidates, and forcibly restraining poll workers from assisting, as permitted by state laws, voters to cast their ballots.” They also hung posters in and around polling places that read, in bright red ink: “Warning: This Area Is Being Patrolled by the National Ballot Security Task Force: It Is a Crime to Falsify a Ballot or to Violate Election Laws.” The posters offered a $1,000 reward for any information about illegal voting. Nowhere did they say that they had been paid for by the GOP, as federal election law required.

In the end, the Republican candidate, Tom Kean, won the governor’s race by just 1,797 votes. Democrats and civil rights groups charged that the activities of the task force deterred large numbers of would-be voters from casting a ballot.

The following year, the RNC settled the Democratic Party’s lawsuit over the episode by signing the consent decree. The RNC agreed to no longer conduct a range of “ballot security” activities, including questioning voters about their eligibility, deputizing people as law enforcement, and targeting voters casting ballots in minority-heavy districts.

In the almost four decades since then, the Republican strategy to suppress voting, especially the votes of racial minorities, has gotten much more sophisticated. Today, the GOP relies primarily not on under-the-radar Election Day dirty tricks, but rather on facially neutral laws and regulations, such as voter ID, which tend to hit nonwhite and poor voters hardest. But the GOP has never been able to bring itself to fully abandon the kind of tactics it used to such good effect in New Jersey back in 1981. Indeed, the consent decree’s history suggests how schemes like these have often been central to the party’s political strategy.

Republicans waited just four years to resume their “ballot security” tactics. Ahead of the 1986 midterms, the RNC conducted another caging scheme in a hard-fought contest, sending non-forwardable letters to around 350,000 predominantly black voters in Louisiana. “[T]his program will eliminate at least 60,000–80,000 folks from the rolls,” the RNC’s Midwest political director wrote to its Southern political director in a memo that was unearthed after some voters filed another lawsuit against the party that year. “[T]his could keep the black vote down considerably.”

Claiming the RNC had violated the 1982 consent decree, Democrats sued again. Another settlement ensured that the decree was strengthened to require the RNC to get a federal court’s sign-off before doing any ballot security activities; its language was also revised to more clearly bar voter caging.

Four years later, the RNC was hauled into court again. Days before the 1990 elections, Republicans sent postcards to some 150,000 North Carolina voters, 97 percent of whom were black. They read: “When you enter the voting enclosure, you will be asked to state your name, residence and period of residence in that precinct. You must have lived in that precinct for at least the previous 30 days or you will not be allowed to vote. It is a federal crime, punishable by up to five years in jail, to knowingly give false information about your name, residence or period of residence to an election official.” The chair of the state GOP said the letters were supposed to go to voters who had recently moved, but admitted that some voters who hadn’t moved in years also received them.

By the 1990s, the bogeyman of Democratic voter fraud was becoming a key element in the GOP’s core message. Over the next three decades, Republican election strategists became experts at spreading the urban myth of widespread illegal voting, the better to suppress voting by Democratic-leaning groups.

They were spurred to action in part by the 1993 National Voter Registration Act, known as the motor voter law, which significantly expanded access to the voting rolls, especially for marginalized groups, by requiring that states offer the opportunity to register at the DMV and other government agencies. The measure, warned outraged Alabama Republican Representative Spencer Bachus on the floor of the House, “will result in the registration of millions of welfare recipients, illegal aliens, and taxpayer-funded entitlement program recipients. They’ll win.”

The Florida 2000 election fiasco brought home to both sides how, in a close race, the rules for voting can make all the difference. It’s worth remembering that George W. Bush’s eventual win was due not only to the Supreme Court, but also to a preelection purge that removed more than 12,000 eligible voters because it wrongly identified them as former felons.

Four years later, Republican efforts to cause chaos at the polls went national—or close to it. The GOP launched programs to challenge the eligibility of tens of thousands of voters in the election’s key swing states, including Ohio, Florida, Pennsylvania, Michigan, and Wisconsin. “If we do not suppress the Detroit vote, we’re going to have a tough time in this election,” one Michigan state lawmaker told a meeting of GOP activists. Even the Bush administration itself lent a hand: Attorney General John Ashcroft told his staff of U.S. attorneys to meet with election officials and conduct investigations into voter fraud on Election Day if necessary, The Wall Street Journal reported.

In Ohio, the election’s most pivotal state, Republicans sent around 232,000 letters to newly registered voters. State party officials then used returned mail to challenge more than 35,000 voters in predominantly minority areas. RNC chair Ed Gillespie joined party officials at a press conference hyping the returned mail and claiming rampant fraud at the polls. A voter filed suit, alleging that the RNC was violating the consent decree, citing emails that showed coordination on the scheme between the RNC and the Ohio GOP. But a federal appeals court ultimately found the state party was in charge of the effort and allowed the challenges to go forward.

Republicans recruited about 3,600 paid workers statewide to level the challenges at the polls. They were helped by an order from Ken Blackwell, Ohio’s Republican secretary of state, permitting a challenger for every precinct, despite a state law allowing only one per polling place, most of which contain several precincts. In Cuyahoga County, the state’s key Democratic stronghold, more than 14,000 voters were challenged. Statewide, one out of every 25 registered black voters reported being challenged, compared to one out of every 100 registered white voters, and 16 percent of black voters reported intimidation, one study found.

With this blizzard of ballot challenges and other logistical obstacles bogging down the voting process at many predominantly nonwhite polling places, some voters waited in line for hours. Large numbers likely gave up in frustration. Bush ultimately won Ohio by a margin of fewer than 119,000 votes, and won the election over his Democratic opponent, John Kerry.

After this demonstration of the effectiveness of a strategy to block voting, things escalated. In 2006, the Bush administration fired several respected U.S. attorneys for not showing sufficient zeal in targeting alleged voter fraud. Two years later, the GOP presidential candidate, John McCain, warned at a debate that the voter registration group Acorn “is now on the verge of maybe perpetrating one of the greatest frauds in voter history in this country, maybe destroying the fabric of democracy.”

This climate of fear and paranoia, sanctioned and promoted by senior Republican Party leaders, stoked an aggressive poll-monitoring movement on the right. One high-profile activist organization at the vanguard of this effort was the Tea Party–linked True the Vote, which drew charges of voter intimidation after launching in 2009. Three years later, some Ohio voters complained after receiving letters from the group warning that their eligibility was being challenged. The same year, one True the Vote leader told volunteers at a meeting that the group’s goal was to give voters a feeling “like driving and seeing the police following you.”

A few years later, the most powerful man in the Republican Party was using the same kind of language. As the 2016 election approached, Donald Trump repeatedly highlighted the supposed threat of illegal voting, and the urgent need to counter it by monitoring the polls.

At an August 2016 rally in Altoona, Pennsylvania, Trump told supporters essentially to pick up where True the Vote had left off. “Go down to certain areas and watch and study and make sure other people don’t come in and vote five times,” he said. “We have to call up law enforcement and we have to have the sheriffs and the police chiefs and everybody watching.”

Trump then hammered the message home. “The only way they can beat it in my opinion—and I mean this 100 percent—if in certain sections of the state they cheat, OK? So I hope you people can sort of not just vote on the 8th, go around and look and watch other polling places and make sure that it’s 100 percent fine.”

The campaign followed up on these appeals by asking visitors to its website to be a “Trump Election Observer.” Those who signed up for poll-watching duty received an email declaring: “We are going to do everything we are legally allowed to do to stop crooked Hillary from rigging this election. Someone from the campaign will be contacting you soon.” After the election, Trump didn’t drop the issue, tweeting that he actually won the popular vote “if you deduct the millions of people who voted illegally.” During his first meeting with congressional leaders, Trump said that between three and five million noncitizens had voted. These false claims formed the basis of a commission that Trump convened to probe illegal voting. The panel was chaired by Kris Kobach, then the Kansas secretary of state and perhaps the country’s leading advocate for tighter voting restrictions. The commission was shuttered eight months later after failing to find significant evidence of fraud.

As the 2020 election approaches, the GOP is shifting resources to the states—with a particular focus on the critical upper Midwestern swing states, including Wisconsin, that delivered Trump the presidency in 2016. The rules for watching the polls and challenging voters vary from state to state. But Wisconsin is one of four states—the others are Virginia, South Carolina, and Oregon—where poll watchers can challenge someone’s right to vote based only on the suspicion that they’re not eligible. Only six states actively bar poll watchers from directly challenging voters at the polls. This means that a coordinated Republican bid to suppress turnout could break out virtually anywhere that the RNC targets as a must-win state for Trump.

If intimidation efforts do materialize this November, don’t count on the federal government to come to the rescue. Voting rights advocates warn that one of the lesser-known effects of the Supreme Court’s 2013 Shelby County ruling was to cut off a key contingent of impartial federal election observers who had worked in areas with histories of racial discrimination in voting. In 2012, the Justice Department said it dispatched more than 780 observers to polling places across the country to protect against voter suppression and intimidation. In 2016, after Shelby, that number was down to more than 500—and even that figure was thanks to a determined push by DOJ officials.

“We beat the bushes to get out as many people as we could from all different parts of the federal government,” said Justin Levitt, who ran the 2016 operation as deputy assistant attorney general for civil rights in the Obama Justice Department. “But that was really hard.” He added that “DOJ’s going to need to do that again this year if it wants to have a robust presence.”

In the 2018 midterms, the Justice Department did run a relatively extensive program, sending monitors to 35 jurisdictions in 19 states. But with the department now led by William Barr—who has shown a consistent willingness to put Trump’s political interests ahead of those of law enforcement—there’s reason to doubt whether this year’s effort will be as energetic.

Some go further. Gerry Hebert, a former acting chief of the voting section of DOJ’s civil rights division, called the department “an adjunct to the vote suppression effort.” Hebert noted that, under Trump, the Justice Department reversed its position on two major lawsuits filed by the Obama DOJ against restrictive voting rules on the books in Texas and Ohio.

Voter protection advocates tend to be wary of issuing dire public statements about potential voter intimidation, lest they backfire and discourage would-be voters from turning out. But they acknowledge that the new trifecta of threats to the integrity of the 2020 ballot—the end of the 1982 consent decree, the post-Shelby restrictions on DOJ oversight efforts, and the false rhetoric we can expect from Trump as he fights tooth and nail for reelection—offers plenty of reasons to worry.

“We’re very concerned that with an influx of money to support those efforts, there’s a very real prospect of it occurring,” said Julie Houk, a top lawyer at the Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights Under Law, which leads the Election Protection coalition that aims to protect voters at the polls. “I just think it’s going to be all hands on deck—people have to be vigilant.”

Of course, there are plenty of other reasons to worry about something going wrong this fall: Fake news could corrupt the campaign conversation and mislead voters. Foreign cyberattacks could throw the whole thing into chaos. Technological breakdowns like the one that upended the count in the Democratic caucuses in Iowa could leave ballots uncounted or marooned in the digital ether. In the face of this battery of digital-age threats, it would be a grim irony indeed if the 2020 presidential contest ends up undermined by a set of Republican tactics that weren’t even cutting-edge in the Reagan administration.