Just before dawn on a cold April Saturday, Officers Thomas Shea and Walter Scott were patrolling the neighborhood of South Jamaica, Queens, where a rash of parked cars had recently been broken into and stripped for parts. But after a graveyard shift cruising the 103rd Precinct on plainclothes “anti-crime” patrol, Shea and Scott had little to show for their efforts, beyond their discovery of yet another burgled vehicle. Their frustration ticked up when they fielded reports of a taxi carjacking in the area, carried out, according to the radio dispatcher, by “two male Negroes” “twenty-three, twenty-four years of age,” with “possibly a gun.” That car, too, was found abandoned. Jolted out of the humdrum torpor of neighborhood patrol duty, the two white cops were en route back to the station when, near the intersection of 112th Road and New York Boulevard, Scott caught sight of two pedestrians and pulled the car alongside them.

“I got out of the car, identified myself as a cop, and flashed my shield,” Shea later explained, first to other cops on the scene, and then, in more or less the same language, in court. According to him, one of the pedestrians retorted, “Fuck you, you’re not taking me,” and fled with his companion into a nearby vacant lot. Shea chased them until, in his account, the man who had cursed him drew a revolver, at which point Shea was obliged to fire “in self-defense.” As the wounded man fell, he somehow managed to hand the gun to the second pedestrian. Or perhaps he “tossed” it to him. Or maybe he dropped it, and the other pedestrian “bent over to take it”—Shea and Scott described what happened variously and contradictorily. Scott, for his part, confirmed that Shea fired in self-defense, as the first pedestrian spun toward him, gun in hand. Scott also insisted that the second pedestrian used the gun to take a shot at him, causing Scott to return fire himself. Despite Scott’s efforts to pursue the second man, both by car and on foot, his quarry somehow managed to escape, abandoning his fallen companion and ditching the gun along the way.

From the start, Shea’s and Scott’s accounts seemed dubious. First off, the blocking and timeline didn’t make sense. How could Scott have been pursuing the second pedestrian with the car one moment, but have had a clear view of all Shea’s actions at the next? Moreover, even though Shea and Scott both insisted the men had had at least one revolver between them, exhaustive searches of the area yielded nothing. Scott testified that he’d only noticed the pedestrians because their outfits were supposedly the same color as the clothes worn by the alleged carjackers’—but also that the only real “color” he’d seen was that of their skin. In fact, skin color was the only thing he’d clocked—not their age, their height, or their build. “I didn’t notice the size,” he said, “but the color was right.”

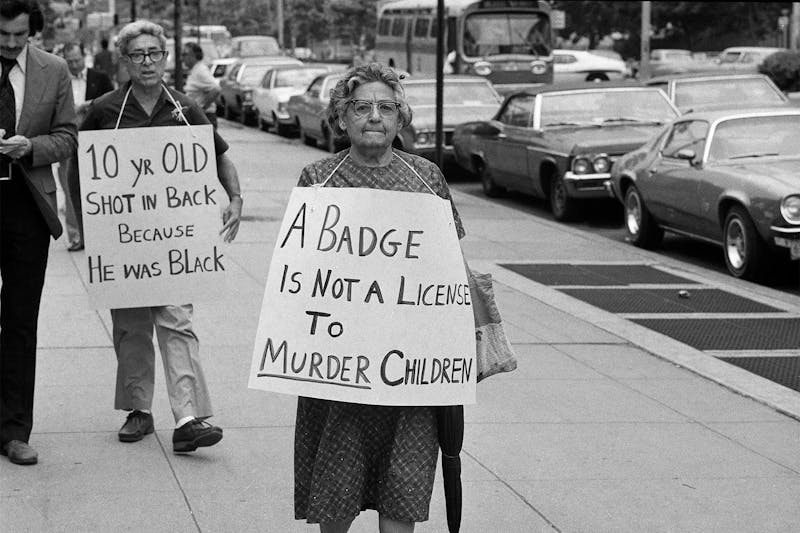

Scott and Shea, in other words, offered accounts that vacillated between absolute certainty and extraordinary vagueness. They were certain the pedestrians had a gun, and certain they’d been compelled to shoot in self-defense. On all other counts, they were terrifically inexact. To be sure, as police tactical trainers are quick to insist, violence can unfold with bewildering speed. Forensic psychologists have documented how memories of trauma can be fragmented and partial, at once hyperrealistic in some details and blank in others. But in the case of Scott and Shea, whose accounts flexibly corroborated each other’s, the combination of confidence and ignorance was suspiciously convenient, because the human being they killed was not a profane, defiant, twentysomething carjacker. He was a 10-year-old boy named Clifford Glover, five feet tall and less than a hundred pounds.

Clifford’s stepfather, Add Armstead, worked an early morning shift at a nearby junkyard, and took Clifford, an aspiring junior mechanic, with him to work on Saturdays. According to Armstead, the plainclothes officers had rolled up without identifying themselves, and Shea had yelled “You black son of a bitch!” as he exited the vehicle, gun in hand. Armstead had just been paid the day before, and had some cash on him; he testified that he believed the white men in street clothes were after him and his money, not the child. The pair fled. When Shea shot Clifford, Armstead, distraught, ran through the streets until he flagged down a squad car driven by a pair of uniformed officers, who searched him and drove him back to the scene. There, as the sun rose, Clifford lay dying. An autopsy revealed that a bullet had struck him from behind, almost exactly in the middle of his back, punching through one of his lungs, shattering ribs, and shredding a major artery on the way out. The slug’s angle of entry made it effectively impossible that Clifford had been shot while turning around, drawing a gun or otherwise.

Nearly half a century has passed since that morning in 1973. Most of the people directly involved are dead. The vacant lot has been cleaned up. What remains is an archive: police reports, courtroom testimony, media accounts. That archive also includes a devastating poem by Audre Lorde, “Power.” “I am trapped on a desert of raw gunshot wounds / and a dead child dragging his shattered black / face off the edge of my sleep,” she wrote. For Lorde, who lived on Staten Island at the time and followed the events surrounding Clifford Glover’s killing closely, the archive threatened a kind of madness. Not just because of what was said in it, but what was said by it, what was implied by virtue of its very existence—its demonstration that no amount of evidence was enough, that documented truths became meaningless when rejected by authority. “There are tapes to prove it,” Lorde wrote of what happened, and what was proved in court. “There are tapes to prove that, too.” The archive was a monument to the intimate relationship between power and language, the gap between truth and accountability, and, ultimately, “the difference between poetry and rhetoric.” It raised a literally life-or-death question: What is the use of language when so often it functions as simply an artifice of brute power? Beyond the bleak reminder that little in the realm of policing has changed for the better over the intervening decades, the killing of Clifford Glover offers a case study in the noxious, all-too-familiar idiom of coptalk.

Today, the official language associated with police violence is notoriously tortured. The phrase “officer-involved shooting” ubiquitously deforms a straightforward locution featuring a subject, a transitive verb, and an object (A cop shot someone!) into an agentless gerund, as if a crankish Victorian ethnographer has translated a foreign expression as proof of some exotic, alien system of thought (An-officer-proximate-to-a-weapon-discharging-has-been!). In breaking news coverage, which frequently reproduces police press releases without modification, the results can run from euphemistic to downright bizarre. “St. Louis police officer killed by colleague who ‘mishandled’ gun, authorities say,” ran coverage of a 2019 incident, in which an off-duty female cop died after an “accidental discharge of a weapon.” Subsequent investigation revealed that she had been shot in the chest in a drunken session of Russian roulette with two on-duty cops, one of whom allegedly had a history of domestic abuse that included forcing girlfriends to play the “game” with him. “An off-duty Hoover police officer is under investigation after a dispute with his wife early Saturday resulted in a handgun being discharged and her being shot,” claimed another news source in Alabama, again citing police officials. The officer in question resigned; two months later, he made headlines once more: “A former Hoover police officer investigated after his gun discharged and struck his wife in February was arrested over the weekend on domestic violence charges.” Guns don’t shoot people, an observer might note, except when they’re the guns of police, who don’t shoot people either, but get mixed up in officer-involved shootings instead.

Coptalk is defined by what at first seem to be paradoxes. On the one hand, it is saturated with anodyne, technical language—the exhaustive precision demanded by official reports and internal reviews. On the other, it is fundamentally evasive. This might seem contradictory, but in fact reveals a kind of systematic cunning: Every i must be dotted and every t crossed expressly to allow officers to enjoy the maximum latitude to do as they will. In a 2017 report, Department of Justice officials commented on how the “Tactical Response Reports” (TRRs) of Chicago police employed meticulous technical language while remaining vague about basic details. Examining one particular episode, in which four cops arrested a man who “tried to physically interfere” with the arrest of another and then attempted to pull away, the DOJ noted:

In describing their actions, one officer checked the boxes for “takedown/emergency handcuffing” and “closed hand strike/punch;” the second checked “open hand strike,” “takedown/emergency handcuffing,” “closed hand strike/punch,” and “kick;” a third officer checked “wristlock,” “arm bar,” “takedown/emergency handcuffing,” “closed hand strike/punch,” and “knee strike;” and the fourth officer checked “knee strike.”

And yet, the DOJ observed, nowhere in their TRRs did the officers indicate “how many strikes they delivered, where they landed, or why each was necessary.” The officers admitted the man had been injured, but they offered no account of exactly how or why. “In the man’s booking photo, he has abrasions on his face,” the DOJ laconically concluded. In such incidents, it is clear, these reports function as a kind of sanitizing fig leaf over raw violence. They’re judiciously employed bits of verbal chaff—in the same register as the familiar yelled cop command to “stop resisting,” which usually comes at the very moment that the cop in question is striking a suspect who is long past the point of being able to do much but sag to the ground and curl up in a fetal position.

There are still other paradoxes. Police departments regularly pride themselves on professionalism, “community” relations, and general restraint. But their claims of prudence sit uneasily alongside the bald aggression of acronyms for task forces like TRASH (Total Resources Against South Bureau Hoodlums), a notorious outfit that the LAPD founded in 1973, and renamed to the slightly more palatable CRASH (substituting “community” for “total” and “street” for “South Bureau”), which operated until 2000; or BOSS (Bureau of Special Services), which the NYPD deployed against black radicals, among other groups, from the 1950s to the 1970s. In L.A., SWAT, perhaps the most celebrated cop acronym of all, did not start out as “Special Weapons and Tactics,” but rather as “Special Weapons Attack Teams,” a phrase dreamed up by the LAPD’s Daryl F. Gates, who in his memoirs says being forced to modify the name by PR-conscious superiors made him feel “crestfallen.” But that was the late 1960s—today, with police militarized like never before, and Punisher skulls plastered on more than a few patrol cars nationwide, the original name might be welcomed.

Coptalk, in any case, is defined by one paradox above all: a total monopoly on deciding what counts as rationality, alongside the police’s conversation-ending deference to their own invocations of that most irrational of affects, fear. The scholar and theorist Rei Terada, writing of the distressing regularity with which police shoot the mentally ill (or as they’ve been known in coptalk, “emotionally disturbed persons,” or EDPs), notes, “From the perspective of the police, resisting arrest is necessarily irrational: they perceive irrational people as resisters, even if that isn’t their intention, and resisters as definitionally crazed.” Drawing a gun, shining a flashlight, and yelling at anyone will understandably terrify that person; for a child, or for someone who is intoxicated or suffering mental health issues, this effect is even more likely. Yet if you hesitate too long or move the wrong way, if you make a gesture that could possibly be conceived as threatening, within seconds, the police can end you. To be in fear for their lives is the police’s criterion for deploying deadly force, while your own terror can be precisely what cops cite as proof that they had no choice but to kill you. “That’s what the higher-ups tell officers to say when something goes awry,” observed Matthew Horace, a distinguished police veteran of both state and federal law enforcement. “You learn it in the police academy and it becomes the mantra of every officer when any shootings occur. And who can prove that you weren’t in fear for your life, even if the fear was caused by something improper that you yourself did.”

For as long as there have been police in America, there has been coptalk. But the euphemism and officialese have appeared to worsen over the decades. The headlines that followed the killing of Clifford Glover seem, in retrospect, almost bracingly straightforward. “Office Kills a Suspect, 10; a Murder Charge is Filed” proclaimed The New York Times the next day. As the journalist Thomas Hauser documents in his excellent 1980 history of the episode, The Trial of Patrolman Thomas Shea, the public outcry and court case that ensued were explosive. Clifford himself was dead, and so Shea’s defenders, the Patrolmen’s Benevolent Association (PBA), focused on disparaging the only civilian left standing. For their part, the prosecution delivered a bombshell. After getting Scott to nail down his supposed movements in the lot, and confirm his insistence that he had had a brief but entirely professional interaction with the fatally wounded Clifford, the prosecution revealed that those moments had in fact been recorded by their walkie-talkies. And then, to an awestruck courtroom, they played a tape of patrolman Scott, standing above a dying child whom he had insisted he thought was a normal-size adult, clearly saying, Die, you little fuck.

Two decades later, in 1994, a city investigation into NYPD corruption found that lying on the stand was endemic among New York police. When evidence was scanty, or when misconduct needed to be covered up, police routinely perjured themselves to make sure case outcomes turned out as desired. The practice was so common, one police officer disclosed, NYPD cops even had a word for it: “Behind closed doors, we call it testilying.”

Testilying remains an intransigent problem in the NYPD, and in police departments around the country, to this day. In 1974, on the stand and under oath, Scott flatly denied that the recording of his own voice saying Die, you little fuck was his. The brazen falsehood was only compounded when a sergeant, one of Scott’s superiors, clumsily tried, also under oath, to claim it had been him on the tape. His gambit imploded under only light cross-examination: There was no question that the words were Scott’s, and Scott’s alone.

But somehow, it didn’t seem to matter. Despite all the contradictions in the police stories, and despite the horrifying audio, the jury found Shea not guilty. Writing a poem the day of Shea’s acquittal, Lorde saw the decision for what it was:

Today that 37 year old white man

with 13 years of police forcing

was set free

by eleven white men who said they were satisfied

justice had been done

and one Black Woman who said

“They convinced me” meaning

they had dragged her 4’10” Black Woman’s frame

over the hot coals

of four centuries of white male approval

until she let go

the first real power she ever had

and lined her own womb with cement

to make a graveyard for our children.

The archive, the official record, was there—there are tapes to prove it. But what counted at the end of the day, over and above the police’s own words, was the simple fact of their power: a power to dispense with the truth as needed. Words, like handcuffs, nightsticks, and guns, were just tools on a cop’s belt, to be used at their discretion to control and brutalize. As far as the police were concerned, the gap between verbiage and truth, between accountability and impunity, and between what things were and what they should be, was a burden to be shunted onto the dead. And that would be shouldered, too, by those who survived them—people like Lorde, who were left to confront “the difference between poetry and rhetoric” as a matter of basic survival and sanity. They, too, were obligated to make recourse to words to process and express their trauma, their fear, and their righteous desire for change. But against the enormous and indifferent edifice of coptalk, how much would anything they said matter?

After the trial, and despite his acquittal, the NYPD dismissed Shea, and Scott as well. “Shea and Scott were not shot at, they were not chasing persons who were armed, they were not in any personal danger, and they had no possible cause to use their guns,” the commissioner’s report explained. “Glover was wrongfully shot, and Shea and Scott thought deceit and fabrication could extricate them.” “Shea is not a wanton killer,” it continued, but “he did display an attitude of reckless abandon and consummate carelessness. Scott, from badly misdirected and unjustified loyalty, elected to cover-up his partner’s wrongful use of deadly force. Shea and Scott do not have the maturity and judgment that is required of all police officers.”

For his part, Shea remained unrepentant. “I shot Clifford Glover because he had a gun,” he told Hauser. “I didn’t know he was only ten, but a ten-year-old can kill you just as dead as an adult.” As Shea saw it, his case was “a classic example of reverse discrimination,” a “media extravaganza” that would never have made the papers if he had been black, or if the media truly had appreciated the sacrifices and risks facing police. “I wonder how many of the people who put my name on the front page of the New York Times and wrote editorials about my going to jail have ever walked through South Jamaica or Harlem,” he asked indignantly. “I wonder how many of them have ever gone to a cop’s funeral and seen a widow bend over to kiss her husband’s face when it’s surrounded by flowers.”

Today, in the era of Blue Lives Matter, the contention that civilians can’t possibly understand what cops undergo is deeply familiar. Police, it is repeated time and again, face situations that civilians can never truly comprehend, and are in no position to morally judge. In this view, police make possible the security civilians take for granted. They are, in the classic phrase, the Thin Blue Line that separates order from chaos. “The first thing we learned,” Shea related to Hauser as he recounted his training, “is that in order to remain viable, society needs police. Our job was to preserve the fabric of society and, toward that end, we were to be given the power, where warranted, to use force.” That unique power—that singular discretion—is understood to be the correlative of work in a profession where “a person faces unknown violence every day.” Against this backdrop, it is only fitting, the argument goes, that police should enjoy compliance, deference, and respect.

Which is all to say: The quintessential role of American police is to function as arbiters of necessity. Above all, they proclaim the necessity of their own existence—no matter what violence that may entail. They are empowered to determine when and what kind of violence is needed, and in their symbolic role as peacekeepers they also supply an object lesson in the necessary violence of society itself. Whenever a given incidence of police violence becomes a political issue or prominent news item, mainstream conversation inevitably unfolds within the terms of a given, unstated proposition: Sure, all this is bad, but we have to have the police—how could we not?

Whether we voice such sentiments in the mode of technocratic reformism or Thin-Blue-Line identitarianism, the same result follows. After each new episode of horror, an efflorescence of coptalk prevents us from imagining any alternative way of defining and enforcing the civil peace. And the starkness of this brand of civilian-grade coptalk demands we think in its own terms alone. What we need is better training, some new slogans, the appeals run. What we will get instead are more pious promises, more technical lingo, more evasive bureaucratese—more coptalk to drape over and explain away the same old blunt encounters between the powerful and the vulnerable, between bullets and flesh. As the police pile gratuitous and labored detail onto stories engineered to justify their existence and absolve them of wrongdoing, everyone else fails to ask whether they are indeed the bedrock of society that at every turn they claim to be. Because talking about cops, even critically, raises the ever-present hazard of simply producing yet more coptalk—new impersonal jargon about threat and necessity and the absence of alternatives on which the survival of the institution depends.

Four years after the killing of Clifford Glover, in her essay “The Transformation of Silence into Language and Action,” Audre Lorde asked: “What are the words you do not yet have? What do you need to say? What are the tyrannies you swallow day by day and attempt to make your own, until you will sicken and die of them?” Four decades later, the questions stand.