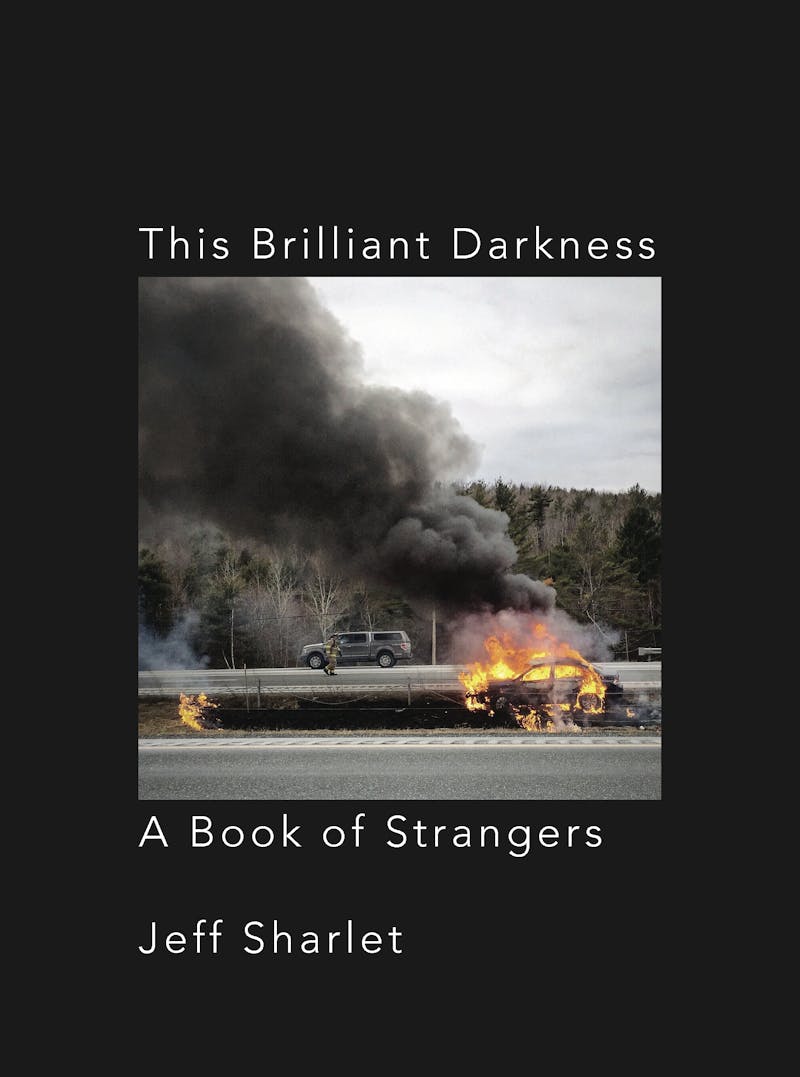

It’s standard practice to begin a text about photography by citing Roland Barthes or Susan Sontag. In the introduction to This Brilliant Darkness: A Book of Strangers, Jeff Sharlet opts for the former: “Cameras, in short, were clocks for seeing.” We might need a new theorist of the photograph; among other reasons, both those thinkers died before the 2007 debut of the iPhone. Maybe Fetty Wap would do: “I seen your ass on Instagram, baby / You became an instant friend, baby.”

Sharlet is best known for The Family, his investigation into a cohort of Christian fundamentalists whose ranks include the disgraced politicos Senator John Ensign and Governor Mark Sanford. If religion was the subject of that book, Darkness is a more humanist text, a collage of photographs and narratives undertaken during a period of personal turmoil: the illness of his father and the aftermath of his own heart attack. The book collects and expands upon work he occasionally posts to Instagram, photos of strangers with snippets explaining their lives. “We should not mistake the Instagram square for a public one,” Sharlet writes in his introduction. “But nor should we miss the dignity afforded by the small solidarities of hashtags: the solidarity of recognition, of seeing one another.”

An insomniac, Sharlet kills time at his local Dunkin’ Donuts, where he photographs the night crew and learns a bit about them. He philosophizes over pictures found in the ooze of the internet: a selfie of a young sailor, a Facebook snapshot of a teen boy brandishing a gun. He travels to Los Angeles’s Skid Row, Ireland, and Russia. He is sometimes taken with a subject and offers multiple images and deeper reporting into their lives; others appear and vanish like you’re scrolling through a feed. Throughout, the author’s tone is awed, reaching for the profound.

This Brilliant Darkness is a project of empathy. We are meant to look at a masseuse who dispenses happy endings in Ireland or a gay hustler in Russia or a shirtless addict on the streets of L.A. and feel we understand them. We are to see them as human. If it all sounds a bit like “Humans of New York”—once a blog, later a book, now an amorphous body of content by photographer Brandon Stanton for which no noun seems appropriate—it should. It’s virtually the same endeavor: to show us that other people exist.

Both Stanton and Sharlet owe a debt to August Sander, the German photographer who undertook the quixotic quest of People of the Twentieth Century, a catalog of all human types of his time. But where Sander included a self-portrait, presenting himself on an equal footing with the others, Sharlet and Stanton privilege both the eye and the I: Neither sees himself as one of a larger cohort but the mitigating lens through which all others are viewed.

This Brilliant Darkness seems like a good-faith endeavor. Sharlet is reeling from his crises and finds a balm in humanity. He tells of meeting an addict when he was a young reporter in San Diego. Sharlet drives the man to the hospital to see to a bad wound he’s been neglecting, Bad Company on the radio. “Years later, when I returned to San Diego, I looked for him, but I never did find him. Which is why, I think, I cannot get that fucking song out of my mind.” There’s no reason to believe this is insincere. Sharlet’s younger self was affected by this chance encounter with a man whose addiction and poverty would have otherwise rendered him invisible.

But is transforming a person into an anecdote truly a way of seeing them? The longest narrative in the book is devoted to Charly Keunang, a Cameroonian living on the streets of L.A., where the police shot and killed him for no particular reason in 2015. It is a terrible story, and perhaps it’s only human to feel the more moved by it when you see pictures of Keunang as a child, or read Sharlet’s reconstruction of the man’s journey to the United States.

There’s a reason family photos circulate when we’re mourning those killed by police violence; conversely, there’s a reason mug shots surface, to curry sympathy for the killers. Images are powerful, manipulative. Sharlet understands this. When he fills in the context—the persecution of gay people in Russia, the plight of impoverished addicts in L.A., the sad realities that shape lives often dismissed as marginal—you cannot help but be touched. But, pace Fetty Wap: Seeing someone on Instagram doesn’t actually make them your instant friend.

In This Brilliant Darkness, Sharlet does not aspire to be August Sander—to create a catalog, or typology. He wants to give us these people’s stories. Sharlet’s project—to remind us of everyone’s fundamental humanity—is maybe the task of all art. But no life can be reduced to a caption on Instagram, and Sharlet’s endeavor, rather than being valiant, begins to feel simplistic. Worse, it feels solipsistic. The images capture moments in time, yes—Barthes’s “clocks of seeing”—but these moments are defined by the photographer and not the subject. He is what makes them matter.

Do these pictures honor or misrepresent? Do they titillate, as pornography, or valorize, as propaganda? Do they accomplish something as art, or, leaving that aside, as journalism? Every reader will have their own answers. This Brilliant Darkness reminded me more than anything of the episode of The Simpsons in which Bart hosts a news broadcast for children, delivering human interest segments that turn out to be a huge hit. As his co-anchor, Lisa, says: “Boy, that phony schmaltz of yours sure is powerful stuff.”