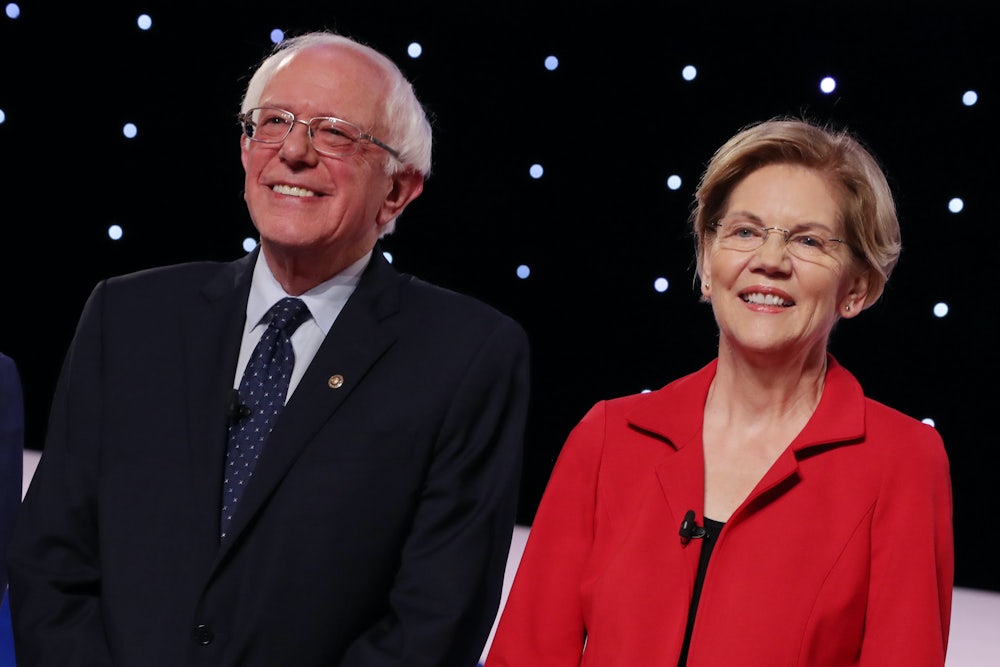

We are several days now into a spat between Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren—the Democratic primary’s two progressives who, as has been widely reported, have observed a pact of nonaggression against each other for the majority of the primary campaign. That arrangement collapsed amid two controversies. The first was brought about by the leak of a Sanders campaign canvasser script that had volunteers challenging Warren’s viability in the general election based on the composition of her coalition in the primary—a kind of argument, it should be said, that has been made against Sanders throughout the race. The second, more serious controversy was brought about by Warren’s allegation that Sanders had privately confessed to her his belief that a woman cannot win the presidency.

Both of these controversies, in their own way, touch upon the question of electability, which polls have told us is front of mind for Democratic voters. As far as Warren’s gender is concerned, even those who argue that Sanders deserves criticism if he made the remark concede that many ordinary Democrats are themselves wary about nominating a woman. “It can be hard to shake the tickle in the back of your brain,” The New York Times’ Michelle Cottle wrote Wednesday, “that Mr. Trump’s retrograde brand of politics—his naked appeals to sexism, racism and other forms of old-school bigotry—can be weaponized all too easily against a woman opponent, who, fairly or not, already faces generic, gender-based hurdles.”

It is clearly true that perceptions of female candidates can be tinted by sexism and that women face more obstacles to success in politics than men. But our last presidential election was instructive. It’s often pointed out, appropriately, that Hillary Clinton won three million more votes than Trump in 2016. It should also be noted that Clinton’s share of the popular vote was not markedly different from the shares won by losing male candidates past—she won a slightly larger proportion of the vote than Mitt Romney and John McCain had previously managed; a slightly smaller proportion than Al Gore and John Kerry.

Her performance, in short, was statistically unremarkable—any additional handicap she might have faced as a woman simply cannot be found in the vote tally. It’s possible that her gender might have cost her some support in the regions of the country critical to an electoral college victory. But the margins in those places were extraordinarily close—to believe that female candidates are doomed to fail is to believe, implausibly, that there were no conceivable scenarios in which Clinton might have garnered the few thousand more votes necessary to carry her to victory. The lesson some Democratic voters have internalized stands opposite to the takeaway that the figures actually offer. Clinton’s narrow loss is hardly evidence that a woman can’t win the presidency. It proves that a woman can.

But received wisdom about electability is powerful precisely because it defies reason and is resistant to critical scrutiny. Like many of the other concepts that shape electoral punditry and political discourse—charisma, qualification, momentum, authenticity—electability is a shibboleth of a political mysticism that “tickles the brain” only because it cannot fully engage it—a drab, gray astrology, maintained by over-caffeinated men.

The whole idea muddles more than it clarifies. Consider the leaders of the 2020 field. The candidate most favored by voters who prioritize electability is Joe Biden: a moderate, appealing to middle of the road voters who want our partisan divisions bridged and political norms restored much more than they favor any particular policy program. He also has considerable baggage. Beyond whatever controversies Hunter Biden’s activities in Ukraine might bring to a general election, Biden can also expect intense scrutiny over his mental fitness and any gaffes he might make on the campaign trail. He could also face the same struggle to juice turnout among the Democratic base as his primary rivals.

Turnout, of course, is central to the electability case for Bernie Sanders, who believes the Democratic electorate can be expanded with disengaged voters, young people, and some Trump supporters, all drawn to his candidacy by ambitious policies like Medicare for All, which would materially benefit the working class. But it’s often said that Sanders’s leftism might turn off the middle-class suburbanites and moderate voters who were integral to Democrats taking the House in 2018. Elizabeth Warren, just to the right of Sanders on policy, does better with more affluent voters but is thought to be too progressive for some and is wrestling with the aforementioned worries about gender. Pete Buttigieg, a man and a moderate, isn’t, and has demonstrated real pull with the same sort of more affluent, educated voters with whom Warren is strong. His lack of experience, however, could fuel doubts about his competence, and he has struggled, moreover, to win black voters—a hurdle some have shakily tied to his sexual orientation. Those worried about this might be willing to consider another white, male moderate—a straight one, with more support among African American voters. This, naturally, brings us back to Joe Biden … and so on.

This is a discourse incapable of producing anything beyond recursive guesswork—hypotheticals within suppositions that send us pacing in circles over questions that no election can actually resolve. The victory or defeat of any given candidate does not foreclose the possibility that they might have performed differently under slightly different circumstances and cannot tell us conclusively whether another candidate might have done better or worse. The 2016 election race drew us close, but not close enough, to understanding this. Any politically engaged person today can rattle off a list of factors that might have tilted the race: Russian interference, irresponsible coverage of the Clinton email scandal, Trump’s omnipresence on cable television, James Comey’s eleventh-hour machinations, the Clinton campaign’s inattention to the Rust Belt. Yet the politically engaged have also taken to believing that electability is a stable and perhaps even measurable quality innate to the candidates themselves. This belief persists despite the victory, in that election, of a man who was widely considered one of the most unelectable candidates ever to seek the presidency. Now many of the sages who rendered that judgment have reconvened to tell us Donald Trump can only be beaten by someone matching a profile—white, male, moderate—that has not won Democrats the presidency in 24 years.

It might work this time around. It also might not. All we can be reasonably sure of is the persistence of a dynamic that Trump’s nomination and election brought into relief—given partisan polarization, and assuming the absence of a strong third-party challenge, just about any candidate from one of our two major political parties can reliably expect to win the support of about half the electorate. Different camps within the Democratic Party have put together plausible theories on what might put one candidate or another over the top in the states and regions necessary to prevail in the electoral college. But these are hermetic arguments that could run up against a variety of competing factors—from unforeseeable world events to the state of the economy to the competence of each campaign organization—once the general election leaves the world of abstraction. The extremely early relevant numbers that we have, the candidate favorability and head-to-head matchups, don’t tell us anything more than what we should already know: We are in for a close race, and the leading Democratic candidates are competitive with Trump.

If this dissatisfies pundits and voters alike, we should ask ourselves how and why they came to agree so closely. Last week, Democratic strategist Jared Leopold made an observation that has been repeatedly echoed by reporters on the ground in the early states. “Cable news has warped voters’ brains and turned everyone into mini-pundits,” he told Politico. “That means candidates need to win not just on policy but on process.” This seems like a product of both the uncertainty that Trump’s election created among voters and shifting norms in political journalism—in which fixed characteristics and variables granular enough to be plugged into statistical models have largely supplanted the naïve horse-race journalism of yesteryear, with its focus on narratives and assumption of close competition. It’s ironic that this mode was dominant within a period when electoral margins were wider and victories were more decisive. That era is now fading—even as candidates run neck and neck more often, and even though it has become more plausible that a specific event or misstep could nudge one candidate or the other just over the line.

In many ways, the new analytical mode has left us better informed. But it is also driving us mad. For over a year, the Democratic primary had been defined by novel policy proposals and theories of change. Now, electability as a concept, a runaway monster, has torn it all down—not just by seizing much of the oxygen and attention available in the discourse but also, as a second-order impact, by distracting and fueling enmity on the left. Until last week, the debate between supporters of Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren had been centered around the records of both candidates, their strategies for achieving their political goals and the substance of those goals themselves, given meaningful differences in perspective on topics like health care and American foreign policy. What we have now is a drearily conventional political slap-fight that grew from competing ideas about who can win the election and how.

Our elections should never be about elections. A voter who has taken to a narrow model of political possibility cannot be told much about the merits of proposals and candidates that aren’t fitted to it. It’s always clarifying to consider just how many of our freedoms have been extended and how many lives have been saved by people and policies that prevailed against perceived odds. The more that ideas like electability arrest our political imagination, the less likely those outcomes will become—an entirely self-fulfilling dynamic that cedes our agency to the judgments rendered by blinkered pundits and jury-rigged algorithms. The democratic principle rests on the assumption that the votes the people cast on candidates and the proposals at hand are, in fact, votes truly for or against those candidates and proposals—that our votes are based not on what we suppose might win, but on what we believe is right. That assumption has always been flawed. But we should work to bring reality as close to it as we can.