When climate change is discussed, especially in the political sphere, it doesn’t take long for the word “existential” to start getting tossed around. This tends to frame the matter in the far-off yet-to-come—if we don’t act now, things will be bad later. But for many communities, especially those inhabited by people of color and Indigenous citizens, climate change is not an issue of the future. It is an issue right now.

In what simultaneously served as both the most pleasant surprise and the most familiar disappointment of Thursday’s Democratic debate, moderator Tim Alberta of Politico posed a fairly straightforward climate policy question: With the understanding that curbing all carbon emissions at this point will only stave off the worst effects of climate change, would the candidates seeking the Democratic nomination support the use of federal funds to relocate American families and businesses away from cities and towns made uninhabitable by environmental factors?

Alberta first tossed the question to Senator Amy Klobuchar, and in the span of 10 seconds, the presidential hopeful from Minnesota stumbled. “I very much hope we will not have to relocate entire cities, but we will probably have to relocate some individual residents,” Klobuchar said.

Klobuchar at least knew well enough to cite a sad viral video from the devastating Paradise fire and quote an Ojibwe saying, recounting how “great leaders make decisions not for this generation but seven generations from now.” For those who pay attention to such things, it’s worth noting that Klobuchar’s broken this line out before. Is it an Ojibwe saying? Or is it Iroquois? Or Seneca? Or is that beside the point when Klobuchar has yet to take a solid position on Enbridge’s Line 3 tar-sands oil pipeline that will cut through the land of the Fond du Lac Band of Lake Superior Chippewa and snake within miles of three other tribal nations? Who’s to say?

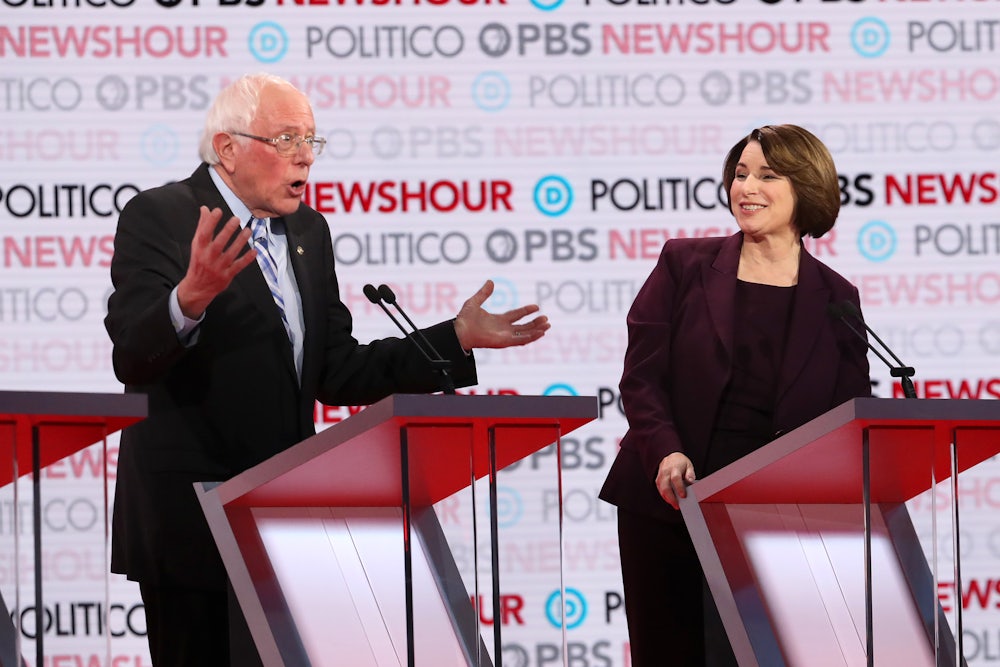

Klobuchar wasn’t alone in her sidestepping of the relocation issue. Vermont Senator Bernie Sanders—who in his first remarks during the debate went out of his way to critique the updated North American trade deal passed by the House for not staking out a position on climate change as it is affected by international trade—also offered a subpar response to Alberta’s question. Sanders attempted to turn the tables on the moderators, which, given the droll level of questioning in these affairs, is typically an easy task. But he fell into the same trap as Klobuchar, claiming that Alberta’s question “misses the mark,” because climate change “is not an issue of relocating people in towns. The issue now is whether we save the planet for our children and grandchildren.”

Again, that is true—the problem is absolutely existential and will determine whether the human race gets to continue doing things like having three-hour debates. But it is also here, right now, at our gates. As Andrew Yang pointed out, relocation efforts are not a hypothetical challenge—which also speaks to an issue with Alberta’s framing of the worthwhile inquiry—they are already underway.

In Louisiana, the state-recognized Biloxi-Chitimacha-Choctaw tribe was forced to leave behind its lands on the Isle de Jean Charles. The lands were not the ancestral home of the tribe but rather a spot in the Louisiana wetlands where they were forced to seek refuge in the nineteenth century, during the harshest years of America’s Manifest Destiny era. Relocation proved an arduous process given the state’s initial refusal to involve them in discussions of where, exactly, they would be relocated. It was further compounded by the ironic reality that the flooding of their lands was not some unfortunate situation of happenstance but the result—in part—of rising Gulf-area water levels caused by the destruction of the natural waterways and state-sanctioned drilling in the Gulf and elsewhere.

As Alberta referenced, the future looks grim for a great many communities, Native and otherwise. The entirety of Miami and other coastal Florida locales are desperately in need of new flood-prevention infrastructure, and entire sections of that city will almost assuredly have to be relocated within the century. A report from the Center for Climate Integrity released in June outlined the multibillion-dollar effort that will be required to relocate the communities most at risk; a terrifying Popula feature by reporter Sarah Miller proved that those with a vested stake in squeezing every last dollar out of wealthy residents hoping to enjoy the skyline while it lasts are making it clear that such efforts will not be undertaken by private industry.

The American federal government has footed the bill for relocating whole communities plenty of times in its past. The only difference is that then, it did it with its weapons pointed at Native men, women, and children—and pulled the trigger on anybody who dared stand up for the ancestral lands coveted by that same government for development and the resulting capital. Sanders was right that Alberta’s question missed the mark, he was just wrong about the manner in which it missed. As the United States—the imperialist, fossil-fuel-guzzling, wealthiest nation on earth—is forced to reckon with the climate disaster it has helped force upon those same communities, the question is not, and cannot be, one of “Should we help them?” It must be a question of “Why haven’t we already started?”