Back in September 2018—an eternity ago in the Trump administration—a self-described “senior official” came forward with a counterintuitive but comforting message.

In an op-ed in The New York Times, the anonymous author decried Trump’s “amorality,” his “preference for autocrats and dictators,” and his “reckless decisions.” But the good news was this: “Many of the senior officials in his own adm inistration are working diligently from within to frustrate parts of his agenda and his worst inclinations.”

Presenting him- or herself as one of these “adults in the room” and pivoting off Trump’s conspiratorial warnings about the operations of the “deep state,” the author coined the phrase “the steady state.” Its guardians were the “unsung heroes … thwarting Mr. Trump’s more misguided impulses.”

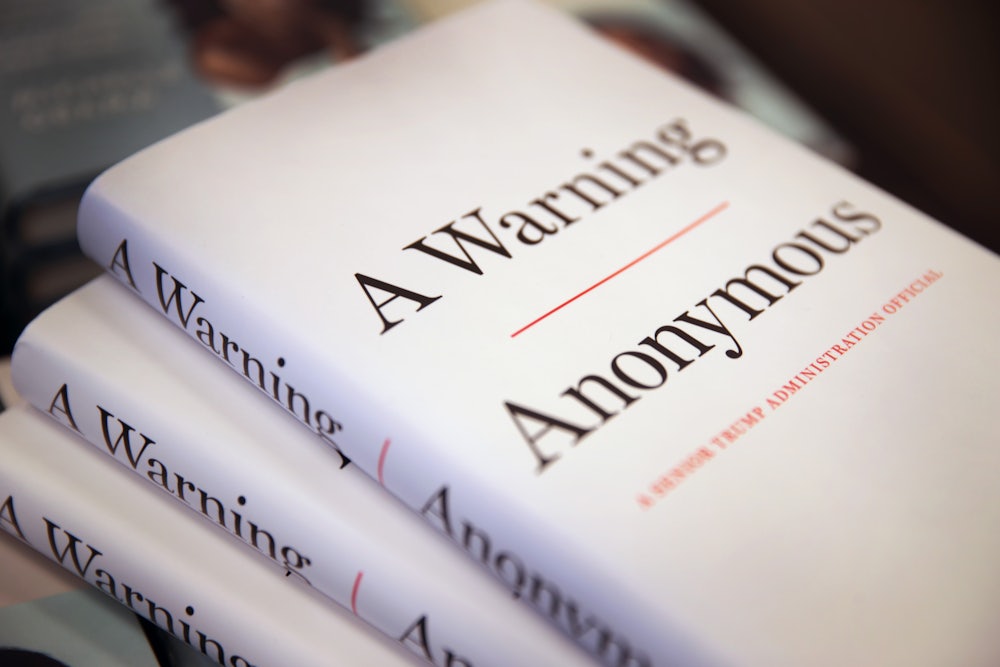

Now, a little more than a year later, the senior official has written a book, titled A Warning and bylined “Anonymous.” The 2018 op-ed received respectful coverage, prompting speculation about the identities of the author and his or her allies. But the book has been overtaken by events, with witnesses testifying under oath in the House’s impeachment proceedings about presidential wrongdoings that A Warning hints at in hushed tones. Such books make headlines with their hitherto-unreported anecdotes. In A Warning, the reader learns of one crisis moment in which senior administration officials almost resigned together in a “midnight self-massacre” to call attention to Trump’s misconduct. In another grim inside account, after judges overruled one of Trump’s hard-line anti-immigrant policies, the president exclaimed: “Let’s get rid of the fucking judges.” What’s more, Anonymous recounts, Trump wanted not only to send unauthorized migrants to a detention camp at Guantanamo Bay but also to designate them as “enemy combatants,” just like terrorists.

With the departure of the seasoned officials who led the “steady state,” such cruel and crackpot ideas never really die. Now Trump might as well be home alone in the White House, left unsupervised to follow what Anonymous described as his most isolationist, xenophobic, misogynist, and authoritarian instincts. While the op-ed seemed to say, “Not to worry, the grown-ups are on the scene,” A Warning can be crudely summarized as follows: “Be very afraid—the grown-ups have headed for the exits.”

Instead of reassuring readers that moderate moles are secretly subverting Trump’s extreme agenda, Anonymous now calls upon Americans, especially those who share his or her own classically conservative views, to assume their responsibilities as citizens and oust Trump from office, preferably by voting him out, rather than impeaching him. “I was wrong about the ‘quiet resistance’ inside the Trump Administration,” Anonymous now admits. “Unelected bureaucrats and cabinet appointees were never going to steer Donald Trump in the right direction in the long run or refine his management style. He is who he is.”

All of which takes us back to the question that convulsed the media and political scene after the appearance of the 2018 Times op-ed: Who is Anonymous? Toward the beginning of A Warning, the author decries the “contemptible parlor game to guess the identity of the author.” All right, then: The book’s text will furnish no skeleton-key evidence of the author’s identity. Meanwhile, in response to the book’s appearance, commentators across the political spectrum have attacked the author for not dropping the mask: If the Trump administration truly does present an existential threat to the American republic, the honorable, classically conservative course of action would be to lodge the message of A Warning in the public record, under the accuser’s name.

In fact, neither the anonymous author nor the literary sleuths deserve condemnation. I suspect, based on my own close reading of the text, that the author is an apolitical retired Navy commander who became chief speechwriter for former Defense Secretary James Mattis. If so, he behaved ethically when he wrote an unsigned op-ed and contracted to expand it into a book.

But now that a whistleblower’s complaint has triggered impeachment hearings, and current and former diplomatic, intelligence, and military officials have testified publicly, anonymity deflects accountability. Because the book includes previously unpublished anecdotes about Trump’s transgressions against constitutional governance and seemingly informed conclusions about his unfitness for office, readers should know who wrote the book and why. My entry in the guess-who-wrote it sweepstakes is the former Pentagon aide Guy Snodgrass, who would know about many events described in the book. He would have honorable reasons to render his judgments. And revealing the author to be an apolitical Navy officer, not a renegade Republican operative, would elevate the nature of his very serious concerns about Trump’s fitness to hold the office of the presidency.

To be sure, any effort to reveal the identity of the author of A Warning is serious business. But the last time policymakers and pundits speculated about an anonymous author, it really was a “parlor game.” On the eve of the 1996 presidential election, Americans prepared for what now appears a relatively low-stakes choice between reelecting the center-left Democratic incumbent, Bill Clinton, or replacing him with the center-right Republican challenger, Bob Dole. Neither represented a threat to American democracy or our alliances abroad. When the novel Primary Colors, a roman à clef about Clinton’s 1992 campaign, was published in January of that year, political and journalistic insiders conjectured about the identity of the anonymous author. The main suspects were current and former Clinton White House and campaign staff and consultants, and several journalists flattered my literary talents (and impugned my loyalty, although I was no longer working for Clinton) by asking me to fess up.

When The Baltimore Sun asked me to review Primary Colors, I read the book carefully and couldn’t help noticing that it read just like Joe Klein’s pieces in Newsweek and, before that, New York magazine. The “tells” included: the novel’s focus on events in New York and Boston (where Klein had also worked); its often over-the-top “tough love” perspective on issues including race, education, and public employee unions; and its implicit sense that the character based on Bill Clinton was promiscuous in his political views as well as his personal life—a point Klein had made earlier under his own byline. More importantly but intangibly, it read just like Klein. And for Klein to turn to his reporter’s notebook to render some of his own insights into thinly disguised fiction was finally a more honorable enterprise than for a Clinton insider to have written a pseudonymous tell-all. As with my guess about A Warning, I want writers to be honorable. (My hunch about Primary Colors was later confirmed by Vassar professor Donald Foster, who used forensic linguistic techniques to establish Klein’s authorship, and The Washington Post, which obtained a manuscript of the book and commissioned a handwriting analysis of the author’s revisions, leading to Klein’s eventual acknowledgment that he did write the novel.)

Having closely read A Warning and the original op-ed, as well as Holding the Line, Snodgrass’s recent memoir of two years with Mattis, I find that my instincts tell me that the same person wrote both books. Why did I suspect Snodgrass enough to buy his book? First, A Warning and the original op-ed both read like they were written by a speechwriter. They both feature short sentences and one-line paragraphs, the frequent use of alliteration, and “reversible raincoat” constructions (Lincoln had a “team of rivals,” Trump has “rival teams”). The two texts also repeat the same words or phrases but in different contexts (as in, “The United States can have an open door without having open borders.”) These tics all reflect a speechwriter’s mandate of writing for the ear as well as the eye.

And as with Klein’s focus on New York as the central setting for Primary Colors, A Warning centers on what Snodgrass would know best, national security and foreign policy issues, while frequently praising Mattis and John McCain. Intriguingly, Anonymous admits Mattis had some differences with McCain, while Snodgrass explains what those differences were: McCain, as chair of the Senate Armed Services Committee, reamed out Mattis for supposedly failing to brief him adequately.

Even more tellingly, Anonymous addresses speechwriters’ specialties—the process of briefing public officials on complex issues and the impact of presidents’ words on Americans’ attitudes—while reverently describing a visit to a speechwriters’ shrine: the shelves in the White House library reserved for bound volumes of presidential papers. One of his original anecdotes would be especially appalling to a speechwriter: Trump apparently forbids staff to take notes at meetings with him. For linguistics mavens with a penchant for forensic analysis, the op-ed uses several words, including “lodestar” and “not moored,” that would be familiar to pilots with a literary bent. And Snodgrass shares the same literary agency—Javelin—with Anonymous.

Reading Snodgrass’s Pentagon memoir, Holding the Line, makes the clues to Anonymous’s identity apparent. As in A Warning, the sentences and paragraphs are pithy and punchy. Every chapter in both books begins with an inspiring but not cliché quotation from a historic figure. Many passages in the books are remarkably similar: the ordeal of conducting a Pentagon briefing for Trump; national security staffers exchanging appalled asides about Trump’s conduct of foreign policy via Twitter; and the arguments for why American alliances strengthen national security and why immigration policy shouldn’t be based on building a border wall. In particular, both books stress that, when briefed about international alliances, Trump derails discussions by griping about how allies are stiffing the U.S., from allegedly miserly NATO contributions to ostensibly one-sided trade policies.

In another revealing quirk, Snodgrass shares Anonymous’s habit of categorizing his cast of characters. Thus, the op-ed distinguishes between the “deep state” that Trump denounces, the “steady state” that Anonymous praises, and the liberal “resistance,” from which he distances himself. Toward the end of A Warning, the author divides Trump’s staff into the Lackeys (true believers), the Steady Staters (capable colleagues), and the Abettors (who neither support nor subvert Trump’s worst goals). He divides the last group, in turn, into the Apologists (who “often display a telltale trait: smiling and nodding at the wrong time”) and the Silent Abettors (who keep quiet but, as he acknowledges, may include some secret, surviving Steady Staters). Similarly, in Holding the Line, Snodgrass classifies two kinds of senior leaders around Mattis: “attenuators,” who took his bad moods in stride, and “amplifiers,” who passed along his harshest criticisms, unfiltered, to their subordinates.

Most important, the two books tell the same story, and Snodgrass is a gifted storyteller. In Holding the Line (a metaphor for service members defending the country but also for steady staters defending the Constitution), Snodgrass describes how Mattis worked together with “the adults”—Secretary of State Rex Tillerson, White House Chief of Staff John Kelly, economic adviser Gary Cohn, and national security adviser H.R. McMaster (who sometimes rubbed Mattis the wrong way)—to defend mainstream defense, diplomatic, and economic policies against Trump’s inchoate impulses. When the adults are overruled and eventually ousted, Snodgrass realizes Trump is irredeemable.

As Anonymous and Snodgrass write, they (to use a plural pronoun for what may well be one person) sympathized with Trump voters’ desire to shake up the political system. Both narrators also wanted Trump to succeed with deregulating the economy, cutting taxes and strengthening the military. In a flourish that seems to be showing off his or her erudition while also padding the text, Anonymous includes lengthy sections evaluating Trump’s character by the ethical standards set by classical thinkers, including Cicero, Marcus Aurelius (a favorite of Mattis), Plato, and Aristotle. Many readers would measure Trump against New Jersey casino owners, not Roman senators and ancient philosophers. But if the author is Snodgrass, he is touchingly sincere. A patriot and a polymath, Snodgrass seems to believe that he can convince many other conservatives to break with Trump by patiently explaining how he has traduced traditional constitutional and moral principles. I wish Snodgrass well. But seeing how many Republican leaders and voters have submerged their values to support their president, I’d sooner bet on Snodgrass’s authorship of A Warning than his strategy to dump Trump.

To be sure, Snodgrass isn’t a perfect fit for Anonymous’s public profile. He wasn’t a White House official, did not work during Trump’s transition (as Anonymous hints he or she did), resigned his job before many events described in the book, and would not have been present at many White House meetings. But compared to other widely rumored suspects whose backgrounds I researched, Snodgrass checks three boxes: He can write. He knows and cares about national security—a major theme of A Warning. And, to borrow from his description of Mattis, he is “a badass” who eventually offended his hero and won a pre-publication battle with the Pentagon over the release of Holding the Line. In fact, Mattis’s spokeswoman has denied that Mattis read Snodgrass’s book and dismissed his former speechwriter as “a junior staffer who took notes at some meetings,” thereby suggesting that note-taking was a point of contention for Snodgrass. No other contender seems to share Snodgrass’s wide-ranging knowledge, story-telling skills, and willingness to make enemies to make important points. And as a self-described Type A personality, Snodgrass probably could write two books at once.

Indeed, Snodgrass may have had help. Perhaps dropping hints, Anonymous cites the Federalist Papers (authored by several Founders under the shared pseudonym Publius) as an inspiration. And Snodgrass writes about working with a network of wordsmiths and policymakers in the White House and other agencies, just as the best Cabinet speechwriters do.

If Snodgrass really is the author of A Warning, it is unfortunate he couldn’t have written one blockbuster book: the story of how an apolitical Naval aviator with conservative values worked with an American hero, James Mattis, while becoming disillusioned with a dishonorable president. This would have been compelling to readers of every viewpoint. It could well have been convincing to the traditional conservatives Anonymous wants to convert. And the classical thinkers whom Anonymous quotes would appreciate the tragedy of an aviator who flew too close to the dying star of a dishonorable presidency.