Earlier this year, at a party in Brooklyn, I had a conversation with a young woman who had recently moved to the area. She was young, tall, pretty, quirky, white, an artist. She really did like the neighborhood, she was telling a group of people, although, she said, there was a lot of crime. There were attempted robberies all the time. Just the other day, there was a face-slashing in the park. She hadn’t witnessed any crime herself, but she followed all these events closely, on an app that tracked police activity. Someone asked why she would do that. Didn’t it just make her worry more? She paused for a second and then replied, “Have you heard of My Favorite Murder?”

My Favorite Murder is a wildly popular podcast that combines two well-proven formulas: the morbid fascination and investigative momentum of a true-crime show like Serial and confessional, comedic banter in the tradition of Marc Maron’s WTF. On each episode, the hosts, Karen Kilgariff and Georgia Hardstark, take turns telling each other about murder cases in an easy but avid manner, as though they were recounting episodes of 48 Hours they watched the night before. They get their facts from TV shows and various not-strictly-authoritative online sources; they’re loose with the details, riff freely, and take long digressions into movies they’ve seen and self-care tips they’ve learned in therapy. Sometimes they cover what they call the “heavy hitters,” such as Jeffrey Dahmer or the JonBenét Ramsey case, but more often they share the kinds of stories you see on late-night news, in which the victim is usually white, female, and, as they describe her, a “badass,” and the perpetrator is “a fucking monster.”

The hosts are funny, sincere, and self-deprecating, irreverent but not flippant, and, since launching the show, in 2016, they have attracted a following of fiercely loyal, mostly female fans, who call themselves Murderinos—a label that has graduated, for many, into a full-blown identity. (Just google “My Favorite Murder tattoo”; you’ll find dozens, if not hundreds.) What Kilgariff and Hardstark offer their listeners isn’t expertise (there are any number of mostly less successful podcasts you can go to for that) but, rather, the performance of a particular type of fandom, as they slip from gruesome killings to mundane personal anecdotes to inside jokes and indignant screeds informed by a girl-power-style feminism. Plenty of true-crime shows, under the guise of serious truth-telling and justice-seeking, are actually calibrated to fuel exactly these kinds of voyeuristic, half-informed, unfocused conversations among their audiences. My Favorite Murder merely articulates the id of such shows.

When you talk about crime, you necessarily talk about punishment, and the way My Favorite Murder deals with criminal justice is particularly revealing of certain currents that run beneath the wider true-crime phenomenon. In a fairly typical moment from an early episode, Kilgariff tells the story of Larry Singleton, who, in 1978, raped a teenage girl, cut off her arms, and left her to die beside the road. She survived, and he served eight years of a 14-year sentence, then went on to commit a murder for which he was sentenced to death. “Unfortunately, he died of cancer in a prison hospital, instead of being fried,” Kilgariff says, in a comment that is both completely casual and, Singleton’s crimes notwithstanding, shockingly bloodthirsty. In live recordings of the show—which the pair perform around the world, to sold-out audiences of thousands—the stories often end with a killer being sentenced to death or executed, and the crowd goes reliably wild.

There is a definite whiff of the Colosseum about the whole thing. But it’s easy to see how you could get swept along to these reactions—they provide the clarity and catharsis that the stories demand. But My Favorite Murder didn’t develop these vindictive tendencies in a vacuum. In fact, the show partakes in a long-standing relationship between the crime-story genre and modern law enforcement, in which the stories we tell about crime and how to stop it prop up a system that is often as much about maintaining fantasies of social order as it is about implementing real justice.

The crime story as we know it today—with a strong element of whodunnit and an emphasis on investigation—sprang up in the nineteenth century, when writers such as the French criminal turned detective Eugène-François Vidocq, Edgar Allan Poe, and Arthur Conan Doyle helped promote the idea of forensic investigation and establish in the popular imagination the now familiar figure of the unfailingly rigorous and rational detective, who must, by narrative necessity, crack the case at the end of the tale. Stories about crime had been popular before this, but they usually emphasized the moral lessons to be learned from the downfall of the guilty. These new stories had little interest in morality or even in character development. Instead, they were like puzzles to be solved, and they each contained a detective or police officer who could be relied on to solve them.

The rise of the modern crime story coincided with the professionalization and bureaucratization of policing and provided a framework for understanding the work of these new law enforcers. The apprehension of criminals had traditionally been a responsibility that was largely shared by the community as a whole, but amid rapid urbanization in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, many cities began instituting professional police forces, which soon started to use recently developed forensic methods to carry out their investigations. In the mid-nineteenth century, Charles Dickens, who was fascinated with the new, scientific approach to law enforcement, wrote that London’s Detective Force:

is so well chosen and trained, proceeds so systematically and quietly, does its business in such a workmanlike manner, and is always so calmly and steadily engaged in the service of the public, that the public really do not know enough of it, to know a tithe of its usefulness.

Popular crime stories, both fictional and not, bolstered an ideal that is still in place today, of a law-enforcement establishment made up of efficient, dispassionate, infallible investigators, quietly protecting us all from chaos by using science and cunning to see hidden but indisputable truths.

In recent decades, as DNA testing and other advancements have solved abandoned cases and overturned old convictions, the public has had to process the fact that, more often than anybody could be comfortable with, the certitude and authority of criminal investigations might be a bit of a sham. Accordingly, the current wave in true crime often deals with the exoneration of the wrongfully convicted. Hit podcasts and documentaries such as Serial, Making a Murderer, and In the Dark showcase the shortcomings of the criminal justice system—the corrupt cops, the flawed science, the forced confessions. Online, communities of amateur sleuths reexamine cold cases, convinced that they can solve them by looking more closely and carefully than the police did. In this self-reflective turn, the lines between the heroes and villains of crime stories are much fuzzier, but the stories still lean on the premise that if the science could be improved, the resources spent, or the bad actors weeded out, the system would work, truth would be known, and justice would be served.

In a way, crime stories, true or otherwise, have always been about self-soothing. They provide reassurance that we live in a stable, knowable world. (Recall how frustrated people were with the ending of the first season of Serial, when the producers refused either to exonerate or condemn Adnan Syed, who had been convicted of killing his girlfriend but insisted that he was innocent.) It’s a genre whose satisfactions derive largely from the finality of the big reveal, and it’s not, consequently, particularly well equipped to deal with nuance, contradiction, and ambiguity.

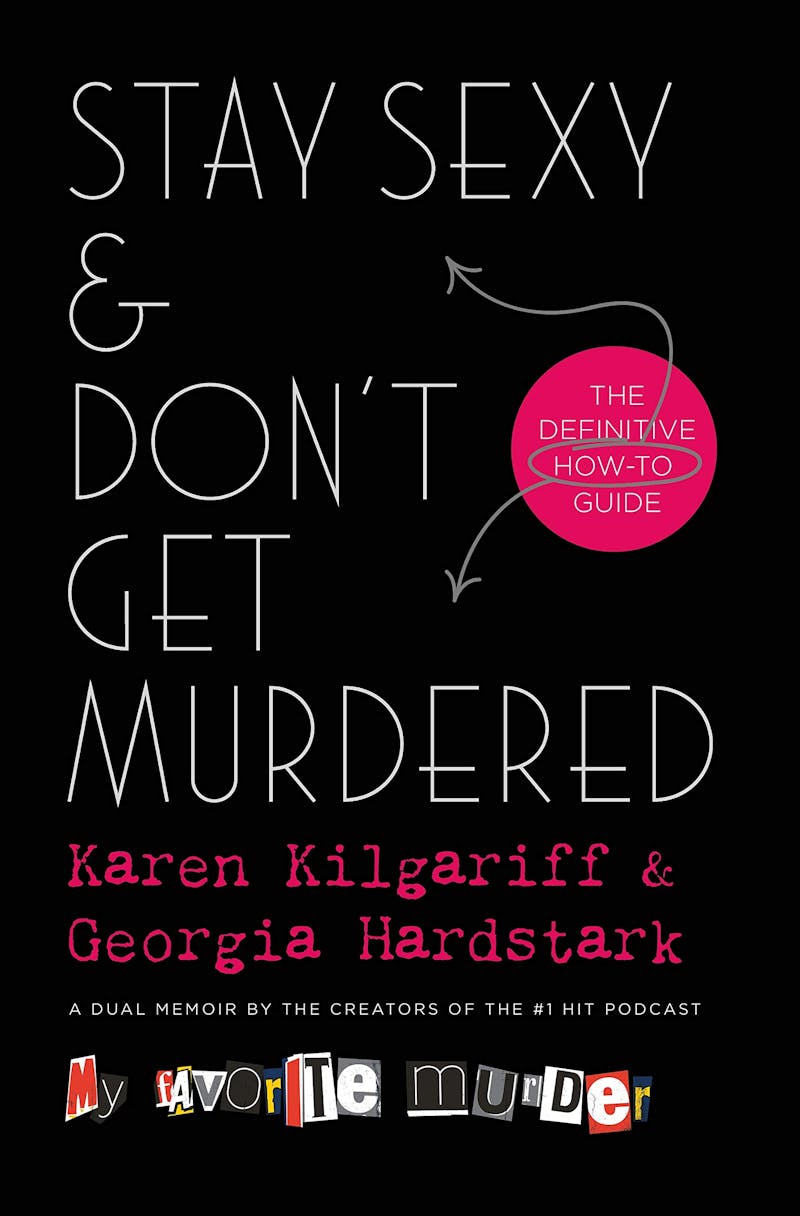

In a book that Kilgariff and Hardstark released earlier this year, Stay Sexy and Don’t Get Murdered (the title comes from the podcast’s primary catchphrase), Hardstark describes discovering true crime as a child. “There was something so satisfying about getting confirmation that the world wasn’t as great as Happy Days or Mr. Belvedere made it out to be,” she writes. “It didn’t take the anxiety away, but it still felt like a fucking triumph.”

A central tenet of My Favorite Murder fandom is that talking about murders is a way to neutralize the anxieties provoked by those very crimes, and, as time has gone on, the show has increasingly leaned in to themes of mental health and self-care. In the podcast’s very early days, the hosts suggested that people needed to hear murder stories because it might help them to stay on alert and avoid getting murdered themselves, but that always felt like a half-baked idea (in the book, Kilgariff compares the approach to Hints From Heloise), and, anyway, they mostly abandoned it when listeners pointed out that it smacked of victim-blaming. Now they focus on the mutual support that Murderinos find just by admitting their anxieties and acknowledging the dangers they face as women in the world.

If you listen to My Favorite Murder, you’ll understand how the young woman I met at that party might have become so preoccupied with tracking police activity. Studies have shown that consuming a lot of crime-related media is correlated with both an increased fear of crime and a higher degree of trust in the competence and good intentions of cops.* And more particularly, in the discourse of My Favorite Murder, seeing oneself as a potential victim is an empowering, feminist assertion. It’s a strike against the gaslighting world that distrusts women and ignores their vulnerabilities. When dwelling on murder becomes a form of self-care, a crime-tracking app might feel like a thundershirt.

But this fixation has repercussions, feeding into a recklessly limited worldview. Kilgariff and Hardstark frequently warn their listeners about the dangers they face, but, in reality, murder rates have been falling for years and, anyway, most homicide victims aren’t white women; they’re black men. In the midst of widespread moves to reduce mass incarceration, the hosts speak approvingly of three-strikes sentencing and “truth in sentencing” laws, which disallow early release, without much thought for the effects such laws have on inmates who aren’t serial killers or psychopaths. While privacy advocates are talking about the need to protect genetic information, My Favorite Murder encourages listeners to submit DNA samples to genetic genealogy companies because it might help police track down a murderer, as it did in the case of the Golden State Killer. Kilgariff and Hardstark are well-intentioned self-described liberals; they express concern about issues such as racial bias in policing and the over-sentencing of nonviolent crimes. But they treat true crime as an essentially personal and nonpolitical subject, so the focus is on the specifics of the story at hand and on the emotional payoff of solving cases and claiming vengeance.

It’s notable that the current true-crime boom has roughly coincided with concern about criminal justice reform becoming a somewhat mainstream issue in the United States. Just as modern crime stories and police forces have roots in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, so does our current system of mass incarceration; the idea of locking people up for long periods of time was an alternative to corporal punishment and frequent executions. But now the inhumanity and untenable bloatedness of the carceral system are widely enough acknowledged that criminal justice reform legislation has been just about the only bipartisan accomplishment of the Trump administration, and Kamala Harris’s background as a prosecutor has often been discussed as a liability in her presidential campaign. An optimist might think that our society is headed toward a serious reevaluation of how we define and deal with transgression. But if that is to happen, we might need to find new stories to tell ourselves about crime.

*An earlier version of this article stated that consumption of crime-related media is associated with a perception of higher crime rates, whereas the study cited actually showed an association between such media and a heightened fear of crime generally.