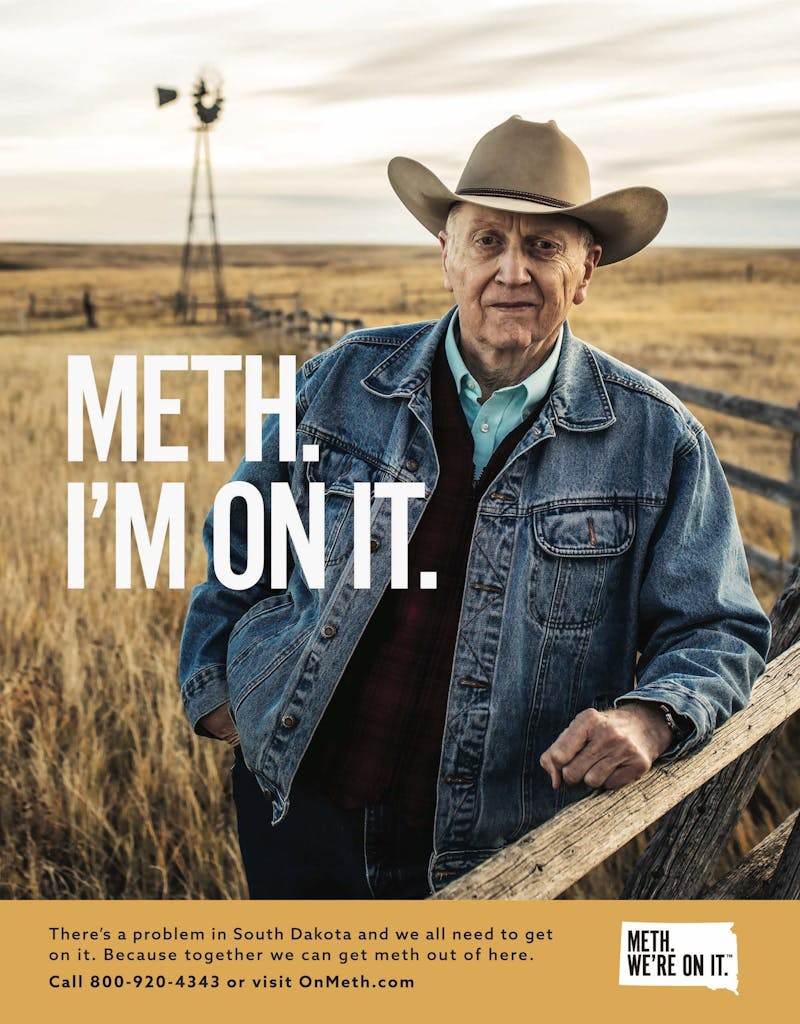

“Meth: We’re On It.” For the briefest of moments Monday evening, these words managed to drown out impeachment analysis as social media cocked a collective eyebrow in the direction of South Dakota.

The slogan is from Republican Governor Kristi Noem’s anti-drug campaign. Complete with a website (the URL is, naturally, onmeth.com), the aim of the series of portraits seeming to announce their subjects are “on” meth is to curb South Dakota’s ongoing issues with substance abuse and drug trafficking. Following initial online bafflement that such questionable copy had made it to print, the state’s secretary of social services attempted to convey in an interview with The New York Times that the state was indeed aware of the implication of overlaying the words on top of photos of South Dakotans:

“I would say that we did expect a reaction,” she said. “It’s a play on words. It’s sort of an irony between healthy South Dakotans, that probably very much aren’t meth users, saying ‘Meth. We’re on it.’ The point is everybody is affected by meth. You don’t have to be a user to be affected by meth. Everybody is.”

While the slogan and the confusing rationale are both objectively hilarious marketing misfires—would it not have been better to create a slogan that was catchy yet did not imply the entire state is on meth?—they mask a reality darker than the one Noem and state officials claim to be highlighting.

South Dakota has a penchant for putting people in jail. Specifically, South Dakota jails drug offenders, and particularly Native citizens, at rates that boggle the mind. And it’s the state’s lock-em-up approach to what is, at its core, a public health and economic crisis that shows not just the absurdity, but also the disingenuousness, of this new campaign.

South Dakota arrests juveniles at a rate double the national average and 25 percent higher than the next closest state’s; of those arrested children, one in five is sent away on drug-related charges. In fact, half of all arrests in the state are for drugs, compared to 29 percent nationally. Looking at the incarcerated population, 64 percent of the women in South Dakota prisons are there for drug arrests; 28 percent of men are locked up for the same reason. Both of those rates are at least double the national average. The soaring rates of drug arrests—up 148 percent from 2010, with over 3,000 meth-specific arrests in 2018—unsurprisingly coincide with the state citizenry’s soaring rate of drug use and substance abuse. In the first six months of 2019 alone, the Drug Enforcement Administration seized 78 pounds of meth in South Dakota; it grabbed just 66 pounds in all of 2018.

Within these already alarming statistics exists another trend: Natives make up 8.7 percent of the South Dakota population but account for half of all arrests in the entire state. On the whole, Native citizens are thrown in jail at a rate 10 times that of white South Dakotans. State officials recently estimated that if one were to add the reservation crime stats to those kept by the state—tribal law enforcement is handled by a combination of the Native nation’s own police force and federal law enforcement—South Dakota’s crime rate would double.

The essential question is why the state’s response has been to throw people, and overwhelmingly Native people, in prison rather than carve out the funds for prevention and rehabilitation.

All of the above trends continue despite the fact that, in 2013, the state legislature passed legislation aimed at addressing prison overcrowding by, theoretically, reducing penalties for nonviolent offenders. However, the South Dakota ACLU found in August that, six years out from the legislative updates, the overall prison population was just barely smaller than it would have been without the bills: a difference of 281 people.

The “on meth” public awareness campaign is accompanied by the announcement of a partnership between the state and the Rosebud Sioux Tribe to have the Sioux operate the only tribe-run Intensive Methamphetamine Treatment Program in the state. It’s a positive development that may yet prove to be merely cosmetic, particularly if the state continues to dedicate its resources to cracking down and locking up Native communities. “In the future,” CNN reported, “Noem said there will be commercials, billboards, Facebook ads, and state agencies working with nonprofits to bring relief to people who are dealing with addiction and the meth epidemic.” Neither these vague promises nor the Sioux-operated treatment program are remotely sufficient to address the drug crisis and the deep inequalities driving it.

Fighting the meth epidemic on sovereign Native land requires federal involvement that has been more than usually absent in the past three years. Some of the tribal nations within the state’s borders are operating on shoestring budgets, with their programs drastically underfunded by Congress and the Trump administration. On Tuesday, the day after the “We’re On It” rollout, a congressional hearing was held to review the 2018 “Broken Promises” report, which detailed how the federal legislature has failed to adequately fund Indian Country services over the last 15 years. The Trump administration cut funding to the Department of the Interior, which houses the Bureau of Indian Affairs, by 12 percent in 2017. That included funding for the Indian Health Service, after-school programs, and the Bureau of Indian Education. Trump’s 2020 proposed budget slashed the IHS “preventive health” budget by $53 million.

In a vacuum, the “Meth: We’re On It” campaign would register as little more than an innocent misstep, a sloppy attempt aimed in the right direction. But politics do not operate in a vacuum. This is the same state and same governor who planned on criminalizing future Keystone XL pipeline protesters just to save themselves and their corporate partners a headache. South Dakota locks up Native people at rates that are only matched by North Dakota and Alaska. What the state needs isn’t a public awareness campaign, but a total overhaul of its punitive approach to drug use in favor of a treatment- and prevention-focused public health program. What its Native nations need is federal funding for basic services that would help keep people from drugs in the first place. Without a serious plan to address these needs, the posters, no matter how many hotline numbers they include at the bottom, are a distraction.