Bless the artist whose work is so sui generis that there’s no noun to accurately describe it. I’m thinking of Truman Capote’s In Cold Blood, often called a “nonfiction novel” for taking liberties with reality, or Karl Ove Knausgaard’s My Struggle, in which part of the struggle is finding a term that encompasses what that series of books aims to do. The writer Ntozake Shange coined “choreopoem” for her 1975 work for colored girls who have considered suicide/when the rainbow is enuf. The word refers to a hybrid of drama and poetry, dance and music. Shange’s masterwork is certainly the text most closely associated with the genre choreopoem, but it’s the category I thought of when reading Bernardine Evaristo’s Girl, Woman, Other.

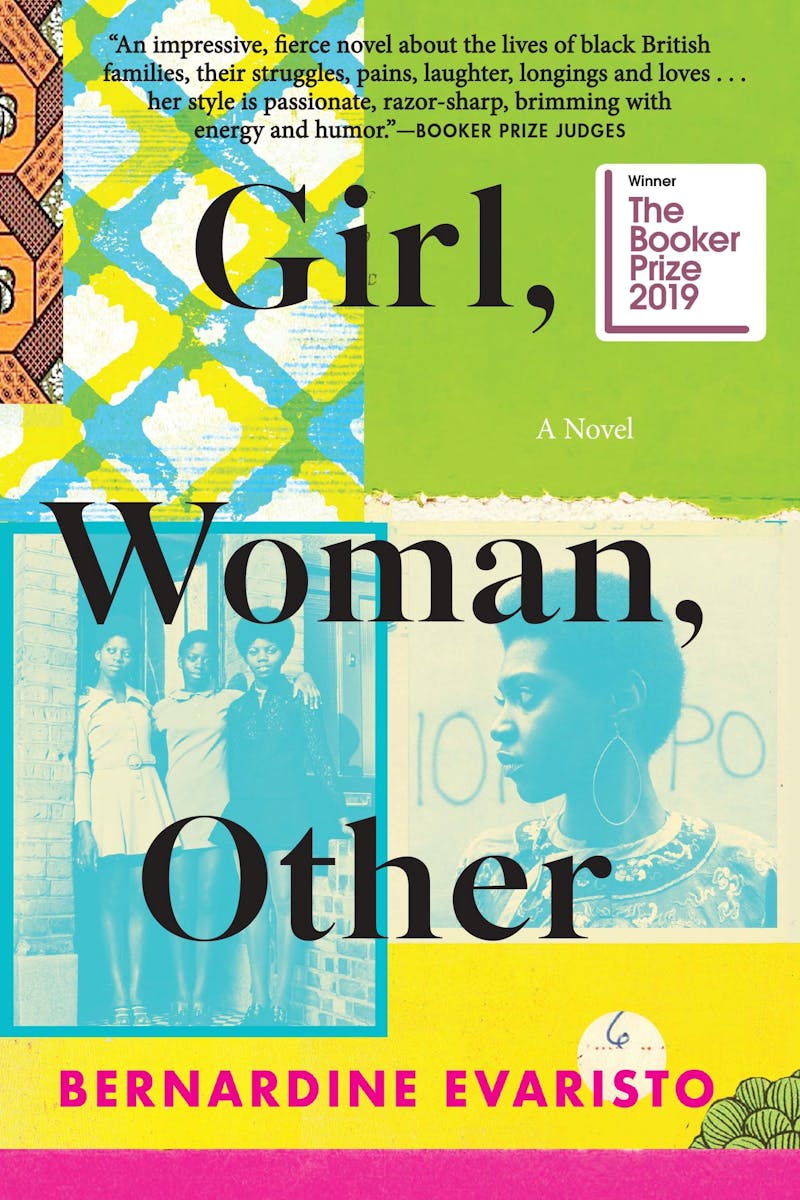

Girl, Woman, Other (which shared this year’s Booker Prize with Margaret Atwood’s The Testaments) is a sprawling book, but too intimate to be considered an epic. It is a close study of the lives of twelve loosely connected people who are all black—a catch-all for immigrants across the diaspora and those of mixed parentage. Eleven are women and one is non-binary; they’re young, they’re middle-aged, they’re elderly. The book roams the globe and through decades, but the story, such as it is, revolves around the opening night of a play at London’s Royal National Theatre.

Unlike a choreopoem, it’s not explicitly meant to be performed, but performance and identity are among the book’s themes. Plus, I could imagine an ambitious audio edition of the book; certainly a prestige television adaptation feels inevitable. To quote the Academy Award winner Mo’Nique: I would like to see it. (And her cast as the abusive, maddening Nzinga.)

Evaristo has written a formally slippery book. I suppose you must call it verse instead of prose. Line breaks supplant punctuation, so phrases pile up rather than congealing into paragraphs. Occasionally, they function more as we see them do in poetry, bringing the reader’s attention to a word or a phrase or an idea (A fast food worker’s lament: “This was her life now/McStupid/McFuckedUp/McStuck/McForever.”) I was skeptical at first; the approach seemed like a gimmick that would inevitably feel tiresome.

I soon stopped noticing the conceit. Despite appearances, the author is writing prose more than anything else, and the book taught me—quite quickly—how to read it. The lines flow into one another, creating a sense of urgency; a neat trick since Evaristo is dealing as much with the quotidian as the big stuff of love and sex, birth and death, violence and joy.

In the first section, we meet Amma, the playwright who is having her opening night and serves as something of a linchpin for the rest of the novel’s cast. In the next section we meet her daughter, Yazz, then her dear old friend Dominique, and so on. There’s no chart in the frontispiece showing how these lives intersect; there’s a pleasure in discovering that as you read.

Each of the twelve sections functions as a discrete biography, but the book has a voice of its own that does not waver with the changes in character. The voice can be poetic, superb at the details: “she slipped free crusty pies filled with apple-flavoured lumps of sugar to the runaway rent boys she befriended who operated around the station.” It can be anthropological, and often funny: “Moroccan lamb, saffron rice, beetroot and kale salad, jollof quinoa and gluten-free pasta for the really irritating fusspots.” It is incisive (“a white girl walking with a black girl is always seen as black-man-friendly”) and often affecting (“Megan was part Ethiopian, part African-American, part Malawian, and part English/which felt weird when you broke it down like that because essentially she was just a complete human being”).

There is not much worry about scene, or the other niceties of a novel. The voice of the book is able to dispatch these: by economically appending exposition, or noting the passage of time, or folding in snatches of dialogue. We meet immigrant strivers and no-nonsense survivors and radical separatists, but that doesn’t get at who these people are. I’d say the effect is impressionistic, but that implies a fuzziness. Each of these characters—and indeed the doting spouses, or abusive girlfriends, or foul-mouthed school chums, or lecherous preachers, or the rest of the human parade—feels specific, and vibrant, and not quite complete, insofar as the best fictional characters remain as elusive and surprising as real people are.

This is a feat; the whole book is. If, ultimately, Girl, Woman, Other is a little too long, I still never tired of its voice. Evaristo is a gifted portraitist, and you marvel at both the people she conjures and the unexpected way she reveals them to you.

I was not persuaded by her biggest attempt at plot—one to do with adoption and a home DNA test. But I was charmed by her tying the book’s tangled mass into a bow by gathering the dozen central characters into the opening night audience of Amma’s play. It’s like those big set pieces that conclude Robert Altman’s best movies, everyone ricocheting around; a little silly, a little earnest, now cue the music and the credits.

In awarding its prize to both Evaristo and Atwood, the Booker violated its own rules, while reminding us that literary prize–giving is a silly endeavor. Art is subjective, impossible to quantify, a matter of taste and so much else; why not choose two winners, or five, or ten? Evaristo should by rights be celebrating the fact that she’s the first black woman to receive this honor, but the judges have sent her into history with a qualifying asterisk instead of a declarative exclamation mark. Yes, prizes are silly. But sometimes they’re deserved.