It is an article of faith among many strategists and activists within the Democratic Party that shifting demographics will be its salvation. The Republican electorate gets older and whiter with every election. Greatest Generation and boomer Fox News addicts can’t live forever, and Big Data shows that it’s merely a matter of time until the modal Republican voter is firmly in the minority.

When I come across this talismanic bit of folk wisdom, I counter with an example that has little relevance to anyone under 40: apartheid-era South Africa. A white minority that made up around 15 percent of the population in that ostensibly “democratic” country kept a death grip on power for decades. Power in a democracy is not about the force of numbers; it is about control of the levers of the law and state power.

The South Africa case may seem extreme, akin to Trump-Hitler analogies. Yet both in spirit and in practice, the modern GOP is embracing a similar strategy of maintaining power in a nation where it has managed to win the popular vote in a presidential election exactly one time since 1992. The politics of blood-and-soil white nationalism, once restricted to the Pat Buchanan fringes and twitchy men distributing homemade pamphlets about the Zionist Occupied Government outside gun shows, are the new mainstream of the right.

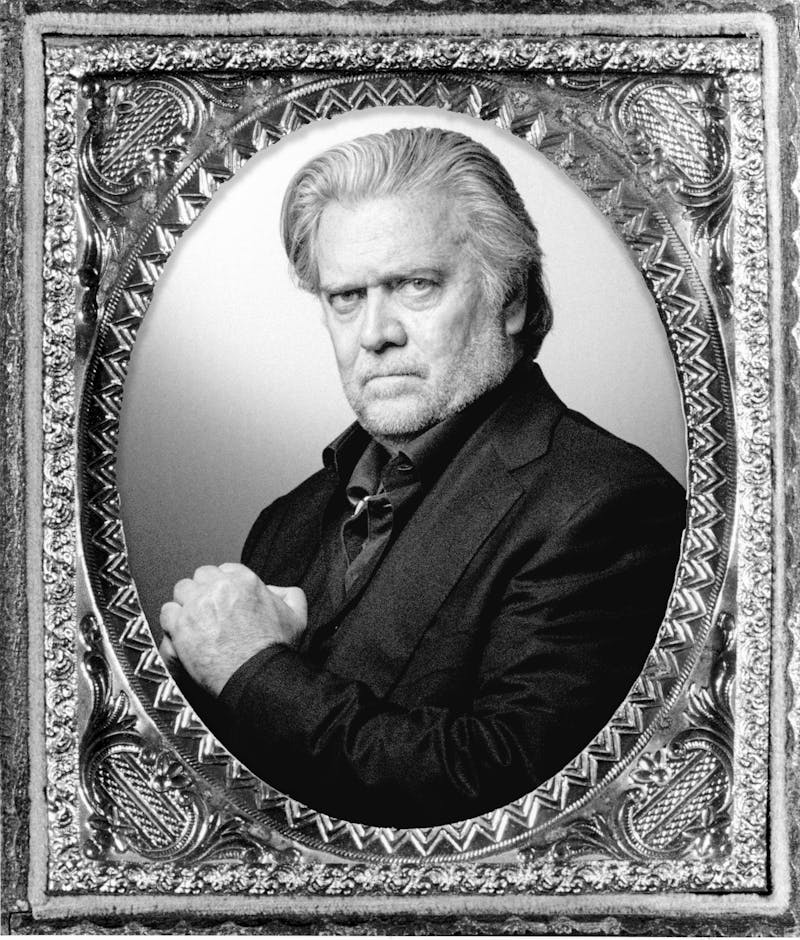

A key tenet of the Trump-led version of these politics is the dismantling of the administrative state—namely, the “deep state” of unelected bureaucrats whose machinations (the argument goes) thwart our conquering-hero president at every turn. Former Trump guru-strategist Steve Bannon built the modern alt-right around, in part, the idea of dismantling the entire administrative state.

In truth, however, breaking the government has been part of the right’s modus operandi since at least Reagan. The impulse to take power in order to hobble, misdirect, and destroy is one of the uniting threads of modern American conservatism. Yet out of the other side of its mouth, the Republican Party is admitting, by action if not by word, that the hated administrative capacity of the state is all that is keeping its power intact long past the point when the conservative movement was advancing an agenda that appealed to a majority of American citizens.

What is the purging of voter rolls in Georgia and elsewhere, or the enactment of an effective poll tax in Florida, but the cynical use of the administrative capacity of the state to manipulate election outcomes by restricting the franchise? What else is the use of state boards of education to kneecap curricula and hand public money to private entities under the guise of school choice? What else can we call anointing Immigration and Customs Enforcement as an all-in-one tool for creating, enacting, and interpreting border policy?

Bannon’s promised dismantling of the administrative state will never happen, for the simple reason that the ability to use the state to tilt the playing field and engineer movement-goal political outcomes that lack popular support is the only thing the leaders of the Trump-era right have left. It turns out the hated deep state is an incredibly useful tool for governing in a manner that represents the interests of a minority of the population that happens to be convinced that it alone is the legitimate nation. Today’s anti-democratic, anti-majoritarian rhetoric on the right reflects only a renewed willingness to say out loud what fire-breathing conservatives have long believed: that regardless of their relative number or election outcomes, a certain group of “Real Americans” defined by race, religion, ideology, and often gender simply deserves to rule.

The combination of anti-state rhetoric and embrace of state power is not a modern development. Of all of the failures of American political journalism, the willingness to repeat the well-flogged rhetorical claim of Republicans that modern conservatives favor “small government” or a rollback of state power is unique in its persistence and duplicity. The size, cost, and reach of the administrative state grows under divided or unified government, whether directed by Republican or Democratic administrations. Talk of “small government” is at best a goal conservatives harbor but never achieve—and at worst a bald lie that supporters hear as a code word for the redirection of social welfare spending to tax cuts and defense.

Despite their rhetoric to the contrary, budgets and deficits grow as persistently under Republican control as under divided or Democratic leadership. The contest is not between one faction that seeks to expand the state and another attempting to shrink it, between statism and anti-statism. Rather, the signature conflict here simply involves an alternating roster of preferences, between New Deal-style liberal statism and conservative statism oriented toward right-wing ends.

The political scientist Ira Katznelson accurately described twentieth-century American politics as a debate not between liberalism and conservatism but around what flavor of liberalism the nation would have. In the postliberal dispensation of twenty-first–century politics, however, political competition concerns the more brute, transactional, and historically momentous question of entrenching liberal and conservative ideas of state power at the center of American governance. Using the federal government to offer immigrants social services or using it to round up immigrants at gunpoint represents, at the structural depths of things, opposite sides of the same coin. The harnessing of bureaucratic power and money is the same; the issuing of orders using the established channels of the executive branch is the same; the translation of electoral victory into meaningful public policy is the same. All that differs is the intent and goal. The vast American administrative state is, in that sense, like a Taco Bell menu—a question of how the same four basic ingredients are shuffled, combined, and prepared to produce different outcomes.

As another group of political scientists—Nicholas F. Jacobs, Desmond King, and Sidney M. Milkis—argue in an article titled “Building a Conservative State,” it is inaccurate to view conservative politics and ideology as aiming to “deconstruct” the administrative state, as Steve Bannon once promised. Instead, the prime goal of the American right has been to redirect state power away from ends it finds objectionable—government attempts to lessen economic inequality, for example—and toward those goals fundamental to its ideology, like national security, immigration restriction, law enforcement, and “stealth” redeployment of government resources through privatization.

During the Reagan years, privatization became both the operational panacea of Republican politics and the Nicene Creed of academic conservatism. It was an article of faith that the mystic demiurge known as free market did things—all things—and did them better and more efficiently than government ever could, full stop. Yet by definition privatization does not fundamentally weaken the state; it merely assigns a new set of actors (who profit handsomely from their efforts, of course) to carry out tasks the state once did directly. This accounting trick, which lives on today in the endless bipartisan fetish for “public-private partnerships,” reached its logical conclusion under George W. Bush in the conduct of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. To sell the public on a war with limited personnel commitment from the military, the Pentagon contracted private companies to supply it with phantom, off-the-books, and extremely expensive consultants.

Similarly, the major domestic policy achievement of the Bush II years was also trumpeted as a government-shrinking turn toward the private sector: the 2003 Medicare prescription drug amendment. Beneath the rhetoric, it was little more than a massive handout to private industry—insurance companies and pharmaceutical manufacturers—delegating to them a task the government defined as a policy objective. In both of these extremely revealing foreign and domestic case studies, state power was neither created nor destroyed; it was simply delegated to a different set of actors.

At its core, modern American conservatism is about fear. While that fear once was directed mainly outward, toward the perils of Communism and, more recently, terrorism, the Trump era brings to full bloom the undercurrent of fear that the people who are unsubtly called Real Americans—white, conservative, Christian, gun-obsessed, and almost always male—will lose their grip on political power. Far from rolling back the administrative state, Trump has aggressively reoriented it toward petty cruelties that are, as the Atlantic political writer Adam Serwer has noted, the entire point. When Trump’s White House takes potshots at vulnerable groups—transgender students, asylum-seekers, Title IX claimants—such gambits work entirely to reinforce the social supremacy of the shrinking white male electorate that feels bottomlessly aggrieved by the conduct, and indeed the existence, of such “enemies.”

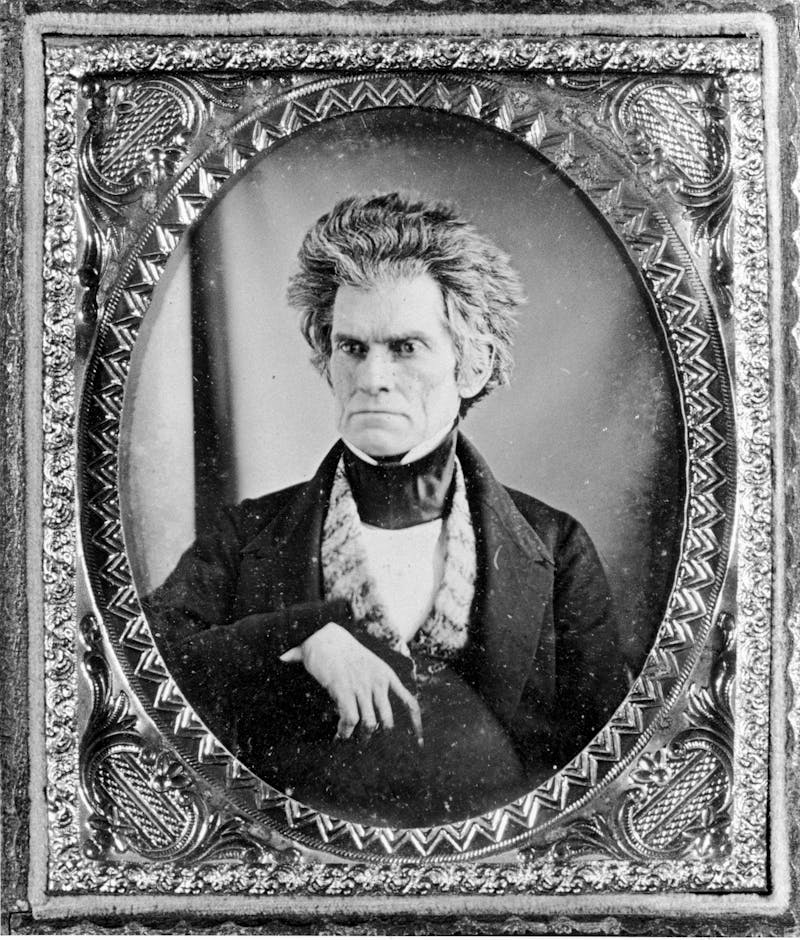

In that sense, Trumpian statism brings American conservatism to a full circle, reuniting its modern goals with those of one of the right’s foundational intellects: John C. Calhoun. Calhoun’s odd and self-serving theories of representation and democratic politics were not limited in influence to the pre-Civil War South. As others have noted, the South Carolinian who held the vice presidency but resigned to return to the Senate has influenced the thinking of key twentieth-century libertarian-right thinkers like James M. Buchanan, who in turn have been extraordinarily influential in shaping the broader direction of American conservative thought.

It is doubtful that President Trump has read deeply of, or could even recognize, Calhoun or his best-known writings like the pro-“states’ rights” manifesto A Disquisition on Government (1851). But the similarities in their worldviews are undeniable. The short version of the Calhoun doctrine is the idea that majority rule runs roughshod over the rights and interests of the minority. If this sounds familiar and like the subject of many of the Federalist Papers, you’re not entirely wrong. But what Calhoun meant by “minority” was not the weak, the vulnerable, or a stigmatized ethnic group. Calhoun’s minority was the small class of landed, moneyed elites who deserve, by natural right, to wield political, social, and economic power.

In other words, Calhoun and his adherents argued that democratic governance is flawed because the undeserving inevitably outnumber the deserving. Calhoun did not put the idea quite so baldly, of course. But every idea he and his ideological successors put forth—state nullification of federal laws, bizarre theories that laws should only be enacted in the case of unanimous nationwide consent, and “concurrent majority rule”—had the singular purpose of protecting the interests and power of the numerically small Southern landowning, slave-owning elite—coincidentally, people just like John C. Calhoun.

Calhoun, in short, believed that a democratic majority in a representative, republican institution was not a basis for government. The only legitimate legislative body was the one that came to the predetermined outcome he and other Southern elites wanted. While it may seem logical that Congress would be the more legitimate body, the Georgia state legislature became more legitimate if Congress failed to give Southern planters what they wanted. All the rest of Calhoun’s democratic theory was intellectual gymnastics to justify beginning with a desired outcome and reverse-engineering an argument for its legitimacy.

Calhoun’s politics were the politics of white supremacy, plain and simple. But even white male strangleholds on national political power—Congress had no women members during the nineteenth century, and only briefly had a small contingent of African American representatives serving during Reconstruction– were not enough in the end. The reason was simple, at least in postbellum American politics: Not all of the nation’s white male elites had economic interests intimately tied to the dehumanizing ownership of other human beings. All benefited from slavery at least indirectly, but not all practiced it directly. So when the slavery détente that defined the first few decades of American nationhood collapsed, Calhoun had to reorient his ideas about democracy around making sure the right white elite men got power.

That is the fear driving modern conservatism—the fear of the white majority, of “Real Americans,” losing hegemony. The solution to that dilemma is the same today, and it’s been throughout our history—to use state power to redefine who counts as a citizen deserving of political rights. And this is where the presidency of Donald Trump and the mass political movement surrounding him connect up with the legacy of Calhounian reaction. Trump is infamously, unapologetically a president who represents not all Americans but his Americans: the real Americans—the ones who support him. The ones who overwhelmingly seem to be white and male and really, really angry that “their” country is being taken from them by interloping others.

Indeed, the Republican Party is now moving into what might be called its high-baroque phase of governmental enclosure by a demographic minority. In state legislatures, GOP leaders are rejiggering power politics among the branches of government to the party’s long-term structural advantage. In North Carolina and Wisconsin, recent election wins by Democratic gubernatorial candidates have resulted in Republican-majority legislatures using the postelection lame-duck period to alter the very foundations of checks and balances in their state constitutions. This brand of scorched-earth politics is common in the latter phases of apartheid-style rule, which typically see a shrinking minority ruthlessly clinging to power. If the faction cannot guarantee its hold on a given position, then the powers of that position must be diminished and redirected to a more reliably controlled institution. If the Republicans cannot ensure their hold on the governorship, then the office itself must be stripped of power—and to hell with the checks and balances.

In the most basic sense, Trump’s promise to “drain the swamp” has inherent appeal to voters whose view of government is unremittingly negative. But as with all modern conservatives, promises to shrink the reach and power of the federal government are pure window dressing. Trump’s budgets have merely drained one part of the swamp—liberal regulatory priorities like education, labor, and environmental protection—and redirected the state’s resources to national defense, veterans’ affairs, and homeland security. But mostly to national defense—the most reliable tributary of the D.C. swamp since the cold war’s heyday.

Beyond the budget rearranging, though, Trump has found the administrative state extremely valuable in redirecting political, economic, and social power to the aggrieved white minority that he believes deserves by natural right to have it. While Calhoun’s white minority consisted almost exclusively of rich landowners, Trump’s is a coalition of the extremely wealthy and the—stop me if you’re sick of this phrase—economically anxious. Absent a unified set of economic priorities and policy ideas, the coalition is held together, no matter how forcefully its most ardent members may insist otherwise, by race. It is a European far-right white nationalist movement rebranded for the United States. “We” and “our” proliferate in their rhetoric. Who “we” are is rarely stated because it is mutually understood. What else is it that the wealthiest of American elites share in common with that guy in a diner outside Harrisburg whom the media will not stop interviewing?

The politics of white state capture differ more in degree than in kind from Calhoun’s day to our own. Since it emanates chiefly from Trump’s presidency, it’s no great surprise that it hinges upon a more explicitly authoritarian model of minority seizure of power than Calhoun’s playbook did; it is rooted less in a rhetoric of states’ rights than a multifront deployment of executive prerogative.

To begin with, Trump’s agenda rests to a striking degree on redirecting policy-making to the federal courts. Even when the GOP controlled the House, Senate, and White House from 2017 to 2019, it had no legislative agenda to speak of beyond tax cuts (a slam-dunk proposition, in any event, for a Republican majority) and repealing the Affordable Care Act (which failed, exactly as all the many Obama-era votes to roll back federally supported health coverage did). Instead, what has united Republicans and arguably explains the establishment party’s willingness to put up with virtually anything from Trump is the desire to jam the federal courts with conservative appointees. The new five-conservative bloc on the Supreme Court, composed mostly of young men (at least by the standards of the judiciary), looks poised to spend 25 years striking down laws and regulations intended to protect workers, the poor, women, people of color, LGBTQ+ people, and anyone who wasn’t smart enough to choose rich parents. Through the Supreme Court and lower federal courts, conservatives now have a long-term lock on power to enact policies they could never secure (at least not without facing chastening consequences at the ballot box) through the democratic process.

If you’re old enough to remember the George W. Bush years, when “activist judge” was the epithet of choice on the right, this turn toward legislating from the bench might seem surprising. But again, activism is always in the eye of the beholder—and a minority movement deprived of any path to long-term majoritarian rule will fall eagerly on any lever of state power it can find that is insulated from the routine democratic pressures of governance. That’s why using the courts to enact, enforce, and protect right-wing uses of state power is the linchpin of modern conservative strategy. Congressional Republicans didn’t spend six years stonewalling Obama nominees to the federal judiciary, only to pass on filling those positions now.

Trump has also embraced the modern right’s longstanding model of presiding over the federal bureaucracy by proxy, via outsourcing, contracting, and privatization. As we’ve noted, this strategic empowerment of the right-wing donor base through conventional sweetheart contracts and featherbedding private-public partnerships creates the illusion of reducing state power, but in reality only passes the baton from one set of actors to another. A different pervasive form of buck-shifting is to devolve decision-making to states—a large majority of which are controlled by Republicans in whole or in part—thereby appeasing old-school conservative intellectuals and slash-and-burn right-wing operatives alike. (In a striking variation on this strategy, the Trump White House has mounted legal challenges to Democratic states pursuing liberal initiatives under their own steam, as in its recent move to block California from enforcing stronger emissions regulations for auto manufacturers.)

In the main, the conservative movement favors states as a convenient instrument to introduce blunt policy initiatives that might not otherwise withstand critical, small-d democratic scrutiny. Rather than gutting public education, why not give states large block grants and let someone else wield the knife? Governors or state legislatures (or both) are only too happy to act out the wildest dreams of a Fox News comment section as state policy. This, too, is an old trick, employed anew in recent efforts to undermine the Affordable Care Act’s provisions for Medicaid expansion.

Not all such undermining directives are outsourced to states, however. In many cases, Trump actively uses state-level initiatives to further his own hold on executive power—and by extension, the policy reign of the modern right. Undermining the federal census or the right-wing obsession with “fraud” as a canard for voter suppression are both taking place at the state level while simultaneously getting a strong push from Trump at the federal level. The presidential commission on voter fraud may have gone down in flames, but plenty of state legislatures and governors have done more than the Trump panel could have hoped to purge voter rolls and restrict voting, as much as feasible, to old white people who never move. The census, paired with the unambiguously aggressive crackdown on immigrants via ICE, is almost certain to return an inaccurate count that once again overrepresents rural areas and lightly populated states—thereby keeping both our national head count of citizens and the apportionments of power in state legislatures, the Electoral College, and elsewhere firmly in the grasp of the minority right.

Together with these other trends, we’re witnessing a rightward putsch in the federal sphere that is a classic calling card of authoritarian rule: the increasing diversion of state power into the rhetorically unassailable ideal of national security. Force-driven initiatives in public life that have resisted basic canons of democratic accountability for years—such as the militarization of law enforcement and the absence of effective oversight for local police—have accelerated with Trump’s enthusiastic support. Immigration enforcement, although in some crucial respects continuing policies established by earlier administrations, has escalated dramatically. Immigration is an issue of overwhelming importance to Trump’s base of Real Americans, who perceive immigrants—at least those who are nonwhite, and cross our borders from what the president has famously dismissed as one or another “shithole country”—as a direct threat to their identity. Right-wing pseudo-populism has always relied on xenophobia as one of its greatest hits, the issue that can produce full-throated cheers among the faithful when nothing else is working.

Finally, Trump uses the presidency to endorse his supporters’ belief in their own inherent right to rule the country, whatever their numbers and whatever the outcome of elections. Every executive action Trump undertakes seeks to employ state power to reward a key conservative minority: moving the Israeli Embassy (end-times conservative Christians), stoking a trade war with China (white Rust Belt economic casualties), securing “campus free speech” (the right-wing grievance industry and media), lashing out pointlessly at transgender people (cultural conservatives), bickering with Iran (neocon war hawks, military-industrial complex dependents), and always, always something new about immigrants (see above).

This approach is also central to his rhetoric, whether on Twitter or at his neo-herrenvolk rallies masquerading as campaign events. There, even the pretense of “presidential” behavior falls away and he tells Real America what it longs to hear: The media is the enemy. The immigrants are coming to rape your daughters. Elections that don’t produce the result you want are fake and illegitimate. Everything is a conspiracy. Your way of life is under attack. You are America, and nobody else is.

White resentment politics are driving a reinvigorated interest in pseudo-intellectual theories about democratic institutions in service of the dawning realization among conservatives that they no longer constitute a majority of the population. Their reaction has been, and will continue to be, to use state power—the courts, elected representatives, state governments—to aggressively redefine who counts and who doesn’t.

Democrats and mainstream media institutions have abetted this line of logic over the years, obsessing over winning the adulation of “hardworking Americans” and a version of “the working class” that always seems to be a white man in a trucker cap and never is a Latina mother of two working in the service industry or driving an Uber. In part, Trump’s America thinks it is more important because everyone has been telling them how important, how authentic, how real they are for decades.

But rarely has the political process acted so decisively and so explicitly to reinforce that message—and with a president openly governing to represent and reward only those who show him fealty, while going well beyond the normal conduct of national governance to punish those who don’t—famously employing the tax code to extract more revenue from residents in urban Democratic strongholds, and to hammer away at the tax base of city governments that have voted to serve as “sanctuary cities” for undocumented immigrants.

One doesn’t have to squint too hard to descry the emergence of apartheid-style state impunity in such measures. Demographic change can’t alter the politics of a nation if a committed minority that believes it alone deserves to govern can manipulate democratic institutions to secure power for itself. Even beyond the lamentable case of South Africa for most of the twentieth century, examples abound of small minorities, defined by race, by ethnicity, by wealth, by religion, or by any other culturally relevant defining factor, wielding power. And they’re proliferating rapidly throughout the world as the neoliberal model of globalizing trade, austerity, and currency exchange continues to collapse.

It wasn’t that long ago in American politics that the entire process of founding and perpetuating state power was held to be off-limits to all but elite white men. Perhaps, then, what we’re witnessing in the Republicans’ recent enthusiastic embrace of state power is something of a reversion to the mean—one that no doubt has the restive shade of John C. Calhoun smiling upon us from whatever level of hell in which he’s now impaneled.