Two Christmases ago, my friend Doug Laux asked me to drive with him on Nevada 375, the Extraterrestrial Highway, to stay in the haunted Clown Motel and then roll to the back gate of Area 51. Naturally, I said yes, but on one condition: My cat Marie Claire had to come along.

Two weeks before, I’d taken the Department of Energy–sponsored tour of the Nevada National Security Site, which abuts Area 51. There, an octogenarian lifelong employee of the federal government named Ernie—who’d gone from being a nuclear technician in the Air Force to working for the Atomic Energy Commission and DOE—led us around on a bus (with windows that could black out, should something classified fly overhead) to various unclassified sites of interest: the Sedan Crater, the Teapot Apple 2 houses, and the low-level radioactive waste disposal area—where Jimmy Hoffa was buried, the area manager joked.

This weekend, thousands of people are expected to descend on Area 51 as a result of a viral internet meme: a Facebook event titled “Storm Area 51, They Can’t Stop All of Us,” to which more than two million people have RSVP’d. For that 2017 trip, though, I wasn’t looking to join a siege. Getting as close as I could to the secret government complex was all about trying to observe the unobservable.

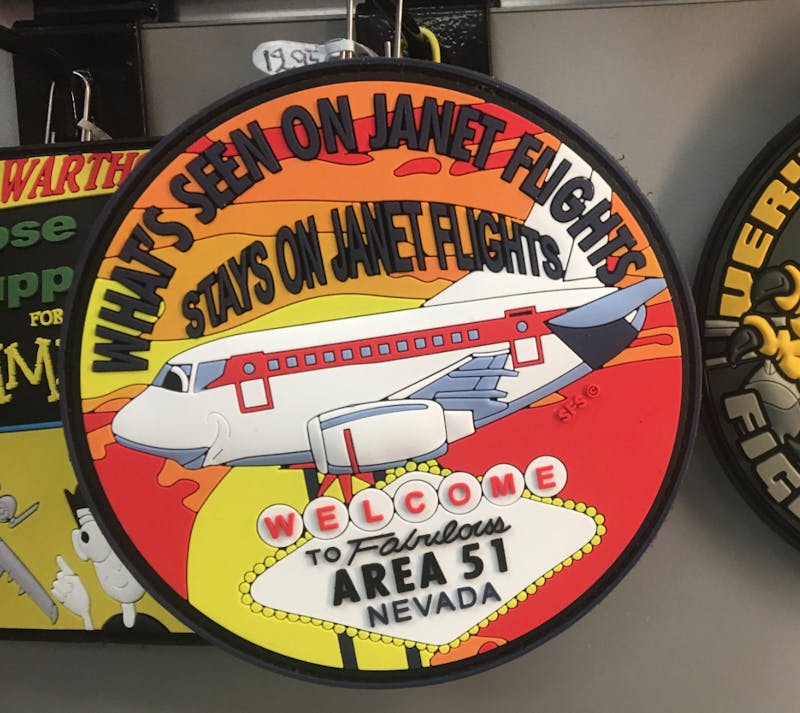

I’d been living in Las Vegas that month; sometimes I’d go down to the strip to watch “Janet Airlines” flights take off from McCarren Airport. This is easy to do: Look for the white passenger jets bereft of any markings except a red stripe. These are classified flights—unofficially, Janet stands for “Just Another Non-Existent Terminal”—responsible for ferrying scientists and workers from the city to “the ranch.”

Taking a blacked-out flight to this particular black site is a tradition as old as the facility itself, and one grounded in tragedy. The idea was brilliant: Put a secret testing ground inside of a secret testing ground, fly in the best scientists, pilots and engineers, and swear them to secrecy. But early on, in 1955, an Air Force C-54 carrying 14 souls through a blizzard crashed near the summit of Mount Charleston, 50 miles west of the Las Vegas strip. Publicly, it was a flight of businessmen, but the crew were technicians sent to work on the design of the then-new U-2 spy plane. The flight’s strict secrecy, including radio silence, may have contributed to the crash, which killed all onboard. “So secret was the crew and passengers’ involvement in the U-2 project,” reads a plaque honoring the Silent Heroes of the Cold War near the crash site, “that the families were not told of the mission or deaths for over four decades.”

I’d already told my family where I was going, and flying wasn’t an option: Doug, Marie Claire and I would drive 150 miles through the desolation of December desert, tiny patches of thin white snow popping against the flat dun. By the time we were a half-hour north of Las Vegas, we hardly saw another car. Later on, we stopped at E-T Fresh Jerky—open daily—to use the restroom, check out the kitsch and buy supplies, and I had a new appreciation for how remote and inhospitable, not to mention de-populated, the area around Area 51 really is.

After World War II, a government study called “Project Nutmeg” was responsible for selecting another continental atomic testing ground. Sites in Alaska, Canada, coastal North Carolina, Texas, Utah, and New Mexico were all considered before the government finally settled on “the area between Las Vegas and Tonopah, Nevada, somewhere on the Las Vegas Bombing and Gunnery Range,” according to an official Department of Energy history released on the project’s 50th anniversary in 2000. America’s atomic tests moved in 1951 from the Trinity site in New Mexico to approximately “1,375 square miles of remote desert and mountain terrain owned and controlled by the Department of Energy” north of Las Vegas, a barren desert where kit foxes, sidewinder rattlesnakes, mule deer, striped whip snakes, coyotes, golden eagles, mountain lions and even the “occasional bighorn sheep and antelope” roam. “Few areas of the continental United States are more ruggedly severe and inhospitable to humans,” the DOE history notes; in the desert between Las Vegas and Tonopah, “water—or the lack thereof—is the dominating climactic characteristic.”

Here, between 1951 and 1992—when President George H.W. Bush signed congressional legislation mandating a moratorium on U.S. nuclear weapons tests—the American government (and, occasionally, the British) would detonate 1,021 nuclear devices. It started with a “shot” code-named “Able” on January 27, 1951—the first of 100 above-ground nuclear explosions in Nevada, which quickly became tourist attractions, according to the Atomic Heritage Foundation:

Mushroom clouds from the atmospheric tests could be seen up to 100 miles away in the distance. This led to increased tourism for Las Vegas, and throughout the 1950s and early 1960s the city capitalized on this interest. Many guests could see clouds, or bursts of light from hotel windows, and the hotels promoted these sights. Some casinos also hosted “dawn parties” and created atomic themed cocktails, encouraging visitors to view the tests. Calendars throughout the city also advertised detonation times, as well as the best viewing spots to see flashes or lights or mushroom clouds.

Under the cover that radioactive detonations provided, the CIA operated an air strip, “5000 feet by 100 feet,” carved out of the Atomic Energy Commission test facility near Groom Lake and called “Watertown,” in a nod to the hellish upstate New York hometown of the Dulles brothers—Allen, then the CIA director, and John Foster, the secretary of state. This airfield, where that ill-fated C-54 had been headed, was used to develop the U-2 spy plane in the early 1950s. In 1961, under Operation Nougat, nuclear tests moved underground. By this time, the CIA was already working on its next secret aircraft, Project Oxcart, which the Air Force would adapt as the SR-71 supersonic spy jet. According to the CIA’s declassified project history, the really impressive thing about Oxcart—despite the fact that it could fly higher and faster than any other airplane in the world—was that “Its development had been carried out in profound secrecy”:

Despite the numerous designers, engineers, skilled and unskilled workers, administrators, and others who had been involved in the affair, no authentic accounts, and indeed scarcely any accounts at all, had leaked. Many aspects have not been revealed to this day, and many are likely to remain classified for some time to come.

To get to the back gate of Area 51, we first passed through Rachel, Nevada, home of the Little A’Le’Inn. There, Pat Travis-Laudenklos and her daughter Connie tend bar, feed the tourists, and manage the motel, a cluster of trailers out back. Behind the bar, there are rows and rows of framed military patches, photographs and signed dollar bills, along with plastic aliens and other knick-knacks, like a Skunk Works “My TR-3B is in the shop” license plate frame. (TR-3B is the designation given to an apocryphal experimental Air Force flying “black triangle,” which many theorists believe to be the real source of of past and current UFO sightings.)

The back gate was west of Rachel, on a tightly packed dirt road that throws up a giant dust cloud, and we decided to roll that way the next day. In the meantime, Doug, Marie Claire, and I checked out the Alien Research Center, a souvenir shop in a Hiko, Nevada, quonset hut that would eventually serve as a basecamp for “Storm Area 51” participants—marked by a two-story grey metal alien sculpture. Inside, the owner encouraged passersby to sign their names on the wall, which Doug and I did before snapping some photos with Marie Claire outside.

We had somewhere to be: the Clown Motel, which is past the Tonopah Test Range—where the F-117 stealth fighter jet was developed. We checked in at the front desk, guarded by hundreds of clown figurines arranged on shelves covering half the lobby. Over the two double beds in our room hung portraits of sad clowns. The cat got bad vibes from the room and hid under the bed, but nothing supernatural occurred until the next morning, when I walked to the front desk to get coffee. For a moment, before I opened the office door, I looked over at the Old Tonopah Cemetery, the eternal resting place of over 300 locals, including 14 miners killed in a 1911 shaft fire.

The woman behind the counter asked me if I’d like any baked goods for breakfast, and I initially declined, until she told me the cookies contained THC, which is legal in Nevada, and she had baked too many of them. I gratefully took all she’d give me, and Doug, Marie Claire, and I set out for the back gate of Area 51.

Despite the hype, there’s really not much to see at the gate. If you’ve ever been on a military base, it’s pretty much the same: standard government-issued guard shacks and fencing, with all-seeing omnidirectional camera orbs mounted on poles—but no security personnel in sight. I thought about taking a picture with Marie Claire, but worried about taking her out of the car. The cookie bag was empty, paranoia was high, and it was Christmas Eve, after all. So we took off, driving back to Las Vegas through emptiness so complete that neither the AM or FM radios could pick up a station.

When the dank Storm Area 51 memes hit the internet, my niece, nephew and stepdaughter all asked if I was going. My reply was an easy no; the whole thing seemed too contrived, a bit of internet legerdemain, using UFOs and aliens to distract the idle and curious from the more interesting—and sinister—goings-on elsewhere in and around the huge desert facility: training friendly terrorists, wargaming nuclear hijackings, concealing toxic exposure, and spending obscene amounts of funds on questionable atomic tests that irradiate the environs, and I thought back to my trip there.

That Christmas Eve, somewhere between Coyote Springs and the Las Vegas Motor Speedway, radio silence was broken. I turned the volume dial up and, hearing one verse, motioned to Doug to pay attention—this was important. In the darkness, speeding toward Vegas, we listened to “A Soldier’s Christmas” together. After the last line: “Carry on Santa, it’s Christmas Day, all is secure,” we both cracked up, perhaps to drown out the rattles of ghosts in our Christmases past, and realized all that was left to do was drive at top speed to the strip and check in to the only luxury hotel where we knew you couldn’t gamble: the Trump Las Vegas.