Drunktown, USA. The Indian Capital of the World. Home.

Nuzzled in the northeast corner of New Mexico, Gallup is for many people a dot on the map, known mostly for its high rates of violence and crime and alcoholism and drug issues. It is, from one narrow point of view, an encapsulation of all the stereotypes that Native people have been running from for the past century. By the 1970s, the alcohol industry had sunk its talons into Gallup, propping up dozens of liquor stores. Three decades later, the alcohol hawkers, payday lenders, and pawnshops all remain. The poverty rate still persistently hovers around 30 percent. As of 2017, the violent crime rate was more than 2.5 times the average of other American cities.

These are the statistics, the numbers that—along with the headlines about the latest slaying or stick-up—shape the public perception not just of Gallup, but of the Diné people (Navajo Nation) who call this land home. But while the statistics confirm that Gallup is still working to recover from a history of colonization and extraction, these numbers do not evoke the feel of the place or give you a sense of its heart. That task, at this moment, is in the hands of Diné poet Jake Skeets.

In Eyes Bottle Dark with a Mouthful of Flowers, Skeets’s illuminating and hauntingly incisive debut poetry collection, Gallup is a place of wonder and discovery, challenging settler ideas of it. It is also a place of reckoning, as the book explores and prods Western norms—such as the gender binary or the commodification of nature—that have so often run up against the cultures of Indigenous people. And Skeets is not scared to turn his gaze inwards to his own community and home town as he explores the stories of violence that surrounded his youth.

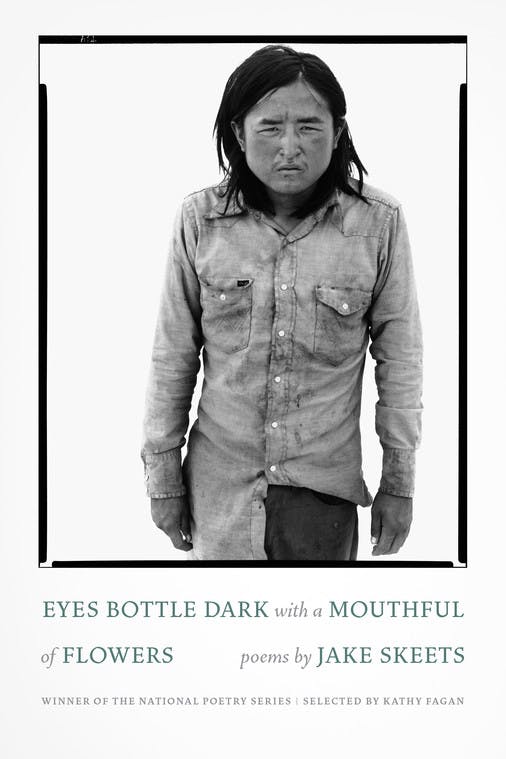

In these poems, Skeets reckons with homophobia and loneliness and death and murder. In his opening poem, “Drunktown” Skeets lays it out plainly: “Men around here only touch when they fuck in a backseat / go for the foul with thirty seconds left / hug their sons after high school graduation / open a keg / stab my uncle forty-seven times behind a liquor store.” (The cover of Eyes Bottle Dark is filled by a beautiful but haunting image that Richard Avedon shot of Skeets’s uncle, who was found murdered in 1979.) By directly confronting a legacy of violence, he refuses to let it impede his journey.

The experiences and resulting feelings Skeets shares about his time in Gallup can feel disarmingly universal—a young heart attempting to grasp love (“Clouds in his throat / six months’ worth. / He bodies into me / half cosmos, half coyote,” Skeets writes in “Virginity”), watching porn in “Gasoline Ceremony,” playing with childhood friends, drinking with them as the years pass by, saying goodbye too soon as they keep ticking away in “Dear Brother.” But Skeets’s writing is also hyper-specific, forged out of the experience of growing up a gay Diné man in a rural community with extractive coal operations at every turn. In a recent interview with Ligeia Magazine, Skeets posed a question that defines his project: “How do I find beauty in brutality and brutality in beauty?”

For all its beguiling lyricism, this is a work determined to point out the contrast-filled moments that define Skeets’s life experience, many of them brought on by a colonizing force that sits on the outskirts of the work, lurking always but never explicitly present in body. In “Glory,” Skeets imbues the plainness of police scanner chatter casually profiling a suspect with the beauty of descriptive language: “Native American male. Early twenties. About 6’2”, 190 pounds. / Has the evening for a face.” Similarly, the three-poem series “In The Fields” details how understanding the land and the creatures that inhabit it requires not just perspective, but also space for thought. In the fields are memories of lust giving way to love; also present are the lingering ghosts of relatives and strangers who have long passed on, invisible reminders of the danger that constantly lurks at the periphery.

The shadowy brand of violence evoked in Eyes Bottle Dark is at once mundane and shocking. “The Indian Capital of the World”—among the most stylistically jarring of Skeets’s pieces—lays out quote after quote from news coverage, detailing incessant anonymous fatal tragedies. Quoting from an article by Lower Brule Sioux citizen, writer, and leftist organizer Nick Estes, Skeets shows how the media and the police stop seeing the people in the news clippings as people. They are bodies. They are background noise more than interruptions, the mere toll of life in Gallup. To believe these characterizations, Skeet shows, is to believe that the loss of hundreds, if not thousands, of lives is inevitable. Skeets drops the headlines down the page, one after another, clustering closer and closer until they overlap with one another, crushing meaning with their combined weight.

As Skeets makes clear, there is another assault underway—on the land that the Diné have shepherded for generations. In “Let There Be Coal,” Skeets lines up the coal industry, one of Navajo Nation’s most substantial economic drivers. He does so not by calling forth scenes of executives plotting in the boardroom, but by showing what forced financial dependency looks like to people who only know the mines as a means of survival, and to fathers who only know physicality as the expression of masculinity: “A boy busting up coal in Window Rock asks his dad, ‘When do we leave for / the next one?’ / His dad sits his coffee down to hit the boy. ‘Coal doesn’t bust itself.’”

The Diné now recognize that these operations are killing the gorgeous landscape and natural habitat around them. But recognizing that fact is a far from being able to detach oneself from it. The space between action and stagnation, like the space between all things, is narrow. “The Navajo word for eye hardens / into the word for war,” Skeets concludes the poem “Buffalograss.”

There is a temptation when approaching Native literature and poetry, one that visited me early in the writing of this review, to connect Skeets’s work to the American publishing industry’s recent embrace of Indigenous writers and poets. After all, the book comes with a coveted blurb from star Cheyenne and Arapaho author Tommy Orange, Pulitzer Prize finalist and author of the heralded 2018 novel and There, There. It would be easy to set Eyes Bottle Dark next to Billy-Ray Belcourt’s The World is a Wound or NDN Coping Mechanisms, to compare Skeets to fellow Diné poets Laura Tohe or Orlando White, or to contrast his focus on the rural culture of Gallup with that of an urban-based gay Native poet like Tommy Pico.

But to do so would fall into a trap. The New Native Renaissance, as Julian Brave Noisecat called it in The Paris Review, does not exist because the publishing industry magically decided overnight that Native authors ought to be read; it emerged because the quality of these writers’ work demanded nothing short of a nationwide audience. Native lit, as a category, is an inherently strange grouping, because Indian Country, now and always, has been just as broad and diverse as the United States, or any other bordered collective.

To read Skeets as a part of this movement is not entirely wrong: The work that appears in Eyes Bottle Dark deserves in some sense to be viewed as the newest addition to a movement to lift up Native voices. But it also deserves to be seen as the debut of a brilliant and transcendent poet, whose work conveys a gorgeous sense of self and of storytelling ability—qualities of the best literature in any tradition.