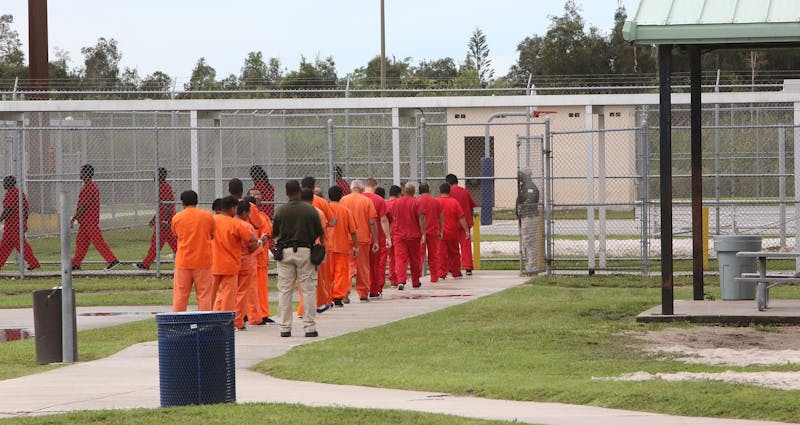

As reports exposing the shockingly brutal conditions at immigrant detention centers have drawn comparisons to ethnic detention compounds under authoritarian regimes, it becomes ever more pressing for the country’s vast immigration bureaucracy to lean on whatever prestige it can muster at the height of the Trump border crackdown. And like everything else connected with this deranged chapter in our national nativist culture war, the present administrative charm offensive is steeped in gruesome irony: As U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) implements policies all but certain to engender lifelong trauma in detained children separated from their families at the border, it is simultaneously promoting an initiative designed to demonstrate compassion and competence toward adult detainees, particularly those diagnosed with mental illnesses. That’s right: An agency now sowing the conditions of mass traumatic stress among child detainees has been trying for years to set up shop as the caregiver of first resort for psychically traumatized undocumented immigrants.

ICE’s crown jewel in this initiative is a Miami facility called the Krome Service Processing Center, which is administered in conjunction with a host of private contractors. Krome was founded in the 1960s as a Cold War military base designed to protect the nation against the threat posed by Fidel Castro’s Cuba. Beginning in 1980, the U.S. government began transitioning it to hold immigration detainees.

ICE officials have previously bragged in the press about facilities at Krome. To hear them tell it, Krome is a state-of-the-art treatment facility for immigrants (documented and otherwise), housed at its nationwide complex of more than 200 detention facilities. It provides stellar medical services, agency officials say, and especially so in the pivotal realm of immigrant mental health.

For a crown jewel, though, Krome is awfully hard to find and access, if you’re not taking part in a prearranged press junket. I went out to see conditions there in June as part of a reporting trip funded by the Project on Government Oversight. The Krome complex is in a vast dead zone on the outskirts of Miami, just on the border of the Everglades. The gigantic Dolphin Mall is nearby, as is a resort and gambling complex run by the Miccosukee Tribe, but the facility sits at the end of an unmarked road off a major freeway. If you don’t have a detained relative or some other reason to know it’s there, it’s out of sight and out of mind. Locating detention camps in such isolated spots is not uncommon for ICE. For all the official hoopla surrounding the level of care supposedly available to suffering detainees in its ambit, Krome, like most other detainee facilities, operates far out of range of sustained public and media scrutiny.

In the years prior to the Trump presidency, this strategy worked like a charm. ICE’s carefully massaged narrative placing Krome on the vanguard of mental health care has gone largely unchallenged—while Krome garnered some press coverage over several decades, only a few outlets ever mentioned its mental health facilities at all, and most that did referenced them positively. A 2015 Miami Herald story, published after the newspaper got an official ICE tour, reported that the former military base—the “only visible remnants from that tense time are three diamond-shaped pads where Nike missiles once stood, ready to thwart an attack from Cuba”—was now “a fully renovated detention center.”

As reporter Alfonso Chardy noted at the time, the facility’s mental health treatment center—known in placid bureaucratese as the Krome Transitional Unit (KTU)—had never before been shown to the media. It had “30 beds where detainees deemed to have behavior problems are monitored and treated before they can join or rejoin the general detainee population,” Chardy wrote. “As part of the treatment, detainees are given group therapy sessions. In one of the day rooms in the transitional unit, a small group of detainees watched Pope Francis’ address to a joint session of Congress ... in which he urged lawmakers to help immigrants.”

A digital news outlet, Statnews.com, was pleased to report in 2016 that even though ICE facilities “have reputations for neglecting mental health”—in some cases, consigning mentally ill detainees to solitary confinement “against the advice of prison doctors” and negligently leaving “immigrants at clear risk of suicide”—Krome was making great strides. The Florida facility had “set up a dedicated mental health wing,” Statnews writer Max Siegelbaum marveled, noting that its staff “works closely with local health professionals, attorneys, and immigration judges with expertise in the field to address the needs of detainees with psychiatric disorders.” This assessment was largely based on observations made by Elizabeth Hildebrand Matherne, “an attorney who has represented detainees.” Matherne, whose now-closed immigration practice was based in Georgia, and who currently works for a civil rights group in Alabama, appears to have little direct experience with Krome detainees. She could not be reached for comment.*

An ICE spokesperson, contacted about the quality of detainee treatment at Krome, replied with a statement citing the facility’s high standards of care for detainees facing both routine and emergency health issues. ICE seeks to ensure “timely and appropriate responses to emergent medical care requests” for all detainees “regardless of location,” the statement read in part. It also cited the Krome center’s high marks in both scheduled and unannounced inspections conducted by third-party contractors: “the facility has repeatedly been found to operate in compliance with federal law and agency policy. Krome was most-recently inspected in February and found to be fully compliant with the agency’s 2011 Performance Based National Detention Standards in each of the 41 categories the inspectors reviewed.”

My own trip to Krome came at the behest of Friends of Miami-Dade Detainees (FOMDD), which got me inside the camp as a community member. I thus became the first journalist to get unsupervised interviews with detainees. What emerged from the visit, along with months of additional reporting, was a far darker and more sinister picture than the one painted by the Trump administration, ICE, and the immigration system’s many media enablers.

Krome, a male-only facility, is designed for 611 detainees but, numerous detainees interviewed allege, is routinely overcrowded. Most detainees are held in about a dozen “pods,” a word that has a more pleasant ring to it than “cells.” Pods are single-room, enclosed rectangular units, roughly the size of a high school gym, where detainees sleep in row after row of steel bunk beds with thin mattresses, according to multiple accounts. Fiberglass chairs are bolted to the floor. Toilets and showers offer no privacy. TVs blare in Spanish and English, and the “pods” emanate an enormous, steady din.

As at detention camps elsewhere around the country, Krome’s broad medical care is horrendous. In addition to being fed terrible food—high-calorie-and-starch institutional fare with little to no nutritional value—detainees face long waits to see doctors and are rarely provided medicines other than Tylenol or other over-the-counter painkillers. What’s more, ICE officials—and the private contractors who run most of the agency’s facilities—have a long record of cost-cutting, avoiding spending that might eat up budgets and profit margins. Because of that, they sometimes refrain from sending detainees in their charge to outside hospitals until their health has deteriorated to a critical point. “You have to wait so long to be seen, you’ll get better or die first,” an advocate at Adelanto—the country’s second-largest detention camp, near Los Angeles—told me when she took me inside there last year.

While some media outlets have covered allegations of abuse and corruption at Krome, they’ve mostly failed—aside from some local publications like the Miami New Times—to seriously investigate the facility’s grotesque charade of providing high-quality mental health care. There is indeed a professionally staffed and supervised Krome Transitional Unit, as the Miami Herald noted in its story, but it holds only a fraction of Krome detainees with mental illnesses, and not the most serious cases.

And conditions at KTU are hardly high-quality, once you stray beyond the range of ICE’s official narrative. At Krome’s main building, I collected testimonials with FOMDD staff and volunteers; together, we interviewed more than a dozen current and former detainees held at the KTU, and they identified a host of glaring problems. (A note about these interviews: Krome does not permit recording devices or transcribing materials for visitors to the facility. As a result, most of the quoted material from these exchanges appears in paraphrased form, based on notations I recorded immediately after leaving the facility.) Some do suffer serious mental ailments predating their arrival at Krome. Many, however, exhibit a variety of mental “illness” that is strictly related to the depression and anger they feel over their unjust detention at a federally run internment camp.

They are periodically allowed to speak to reporters—but up until now, such press encounters have only taken place under the direct supervision of ICE or Krome staff. A number of those held at KTU said they were treated well by staff mental health personnel to whom they had regular access. But much of their treatment reflects the conditions of public mental health care in a rampantly medicalized model of treatment: Many KTU detainees are overly medicated, they allege—and as detainee advocates like Dr. Peggy Mustelier, a clinical psychologist and FOMDD vice chair, and her colleagues at FOMDD note, this regime of pharmaceutical mood management is engineered to render detainees docile, and to dampen the intense rage they feel. Some detainees go into Krome quite sane but emerge mentally broken, she and other FOMDD personnel who have been visiting detainees for many years told me.

But the function of KTU is not so much to heal as to serve as a Potemkin Village. If conditions within KTU are far from sunny, things are far worse for other detainees held within the Krome mental health complex. To begin with, there is the psychiatric ward in Krome’s main building. Even FOMDD and other advocates know little about the ward or its operations, and Krome has denied outside investigators any access to it. Based on descriptions I heard from KTU detainees and advocates, it sounds like the dystopian mental ward in Ken Kesey’s One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, where mentally ill detainees are medicated with powerful psychotropic drugs that reduce them to something resembling zombies. A Somali detainee I’ll call Abshir (the Krome detainees I spoke to didn’t want their names used, due to ongoing legal issues around their deportation status, so I’m giving them aliases throughout) told me that he once needed medication in the middle of the night and was taken to the psychiatric ward to receive it. There he found the ward lit up like a Christmas tree—but all the detainees housed in the ward were so highly medicated, Abshir said, that they continued sleeping in near-comatose states.

Then there is Larkin Community Hospital, where Krome routinely ships off detainees suffering from conditions it deems too acute or bothersome to deal with directly. Larkin is known to some within Florida’s mental health care community as a subpar institution. (A spokesperson for the hospital did not return a request seeking comment.) I asked Abshir how bad Larkin is. He’d never been to Larkin but had talked to several detainees who had. He replied that he hoped never to find out, with a twisted smile that suggested fear.

Krome also houses a padded cell for detainees on suicide watch. A released detainee, who spoke to me by phone, told me about the cell. “They put me on medications and put me in that isolation room and I went through hell,” said the former detainee, who understandably declined to be named even by pseudonym. The U.S. government makes immigrants play “Double Jeopardy,” he noted: He received a sentence of three years’ probation on a nonviolent, drug-related charge. ICE then immediately detained him, and he ended up in the immigration-industrial complex, almost entirely at Krome but with a brief stop at a county jail, for “three years, one week, and a couple of hours.”

ICE regularly detains people for more than a year and argues that it may detain individuals indefinitely (the issue is currently in federal court, where one judge has recently ruled that the agency’s indefinite detention policy is unconstitutional). This person spent thousands of dollars on a useless immigration attorney and was only released after writing his own habeas corpus petition, which he eventually filed in federal court. But he emerged a mentally battered man who is still traumatized by his prolonged stay at Krome. “People in immigration camps get treated worse than people in prisons,” he said. “And in prison, at least you know when you’re going to get out. Murderers are different, but they are treating people who committed petty crimes like demons. Their system is not for humans, it’s for dogs.”

Mustelier went on a guided tour of Krome in 2014 and saw the padded room in which the man was held. “A Krome employee on the tour proudly said, ‘This is where they are stripped down and strapped down,’” Mustelier told me. “I said, ‘What?’ He said, ‘That’s how we do it in the military, and that’s how we do it here.’ He was a very angry man.”

Krome also has a brutal Segregated Housing Unit—“the SHU” in ICE-speak, and “the Box” to some detainees. Prisons more forthrightly label such holding areas as what they are: solitary confinement. Data compiled by the Project on Government Oversight (POGO), an independent watchdog group, found that Krome filed 153 reports of detainees held in solitary confinement between January 2016 and May 2018 (for some individuals, multiple reports may have been sent). In 121 of the reports, solitary confinement was used for discipline. Roughly half the time, detainees placed in solitary had mental illness. They are held in solitary for at least 20 hours a day; they get a brief time outside, which was one hour, according to the former detainee—individually, in a caged area attached to one end of the building. Bigger camps in California and Georgia used solitary far more often, according to POGO.

It’s hard to get an accurate description of what the SHU looks like, because Krome doesn’t allow many people to get a glimpse of it. One FOMDD volunteer saw it during an ICE-organized tour and described it as a “long, narrow modular building with cells lined up next to each other.” The walls of each cell are thick enough that detainees thrown in solitary can’t communicate with each other.

But there’s another reason that it’s hard to get an accurate description of the SHU, explained Mustelier, who has spoken to numerous detainees held there. Everyone who’d told her about it had been “cognitively disorganized”—mentally ill, in other words—so it was “hard to rely on their descriptions.”

These snake-pit conditions in the SHU are unlikely to ever be experienced by the average detainee. But even the KTU—the Potemkin Village ICE officials have so assiduously cultivated as a model of enlightened detainee care—is highly suspect. A man I’ll call Omar—one of three detainees held there whom I interviewed—is from the Middle East but moved to the Miami area in the mid-2000s. He was placed in Krome after he violated a restraining order taken out by his then-wife. (Efforts to find her and her attorneys for comment were unsuccessful.)

Omar said his tenure at KTU has been an unrelieved nightmare. While some of his fellow detainees have been taken in on minor, noncriminal charges—running a red light, for instance—since he has been housed in the KTU, for a ten-month period preceding our interview, he said he has been alongside violent criminals.

Some detainees threatened others with violence or harassment, Omar said. One day around 6 a.m., Omar recalled, he was exhausted and sleeping at a table—lights come up at 5 a.m. in the KTU and are turned off at 10 p.m.—when a detainee thumped the table hard and woke him up. Omar said that he knows how to take care of himself—by fighting with other detainees, if necessary.

He told me he had thus far escaped the SHU, but knew of a number of mentally ill people who had been put into solitary.

The former detainee also knew of such incidents: “There were some people who didn’t even want to shower, they’d be digging through the garbage, they were totally mentally ill, they didn’t know their hands from their feet. One guy, they rushed him and pushed him around. They put him in solitary. No one wanted him in their cell, he stank and was maybe violent.”

Omar said that, as matters stand, the drug regimen in KTU keeps him in a state of near-permanent disorientation. Some days, he said, the staff have told him that he’d be released. Other days, they tell him he will never leave, he told me. Omar did speak highly of one of the psychological team’s members, but said he didn’t like to talk to her, or other staff, about the depth of his sadness, because he found it embarrassing to discuss.

The most painful part of detainment, he said, is separation from his son. Omar was despondent and said he was deeply suicidal. His application for political asylum has not been granted, he said. He told me that he knows many ways to kill himself from his days in a Middle Eastern country’s military—by slashing his wrists, by hanging himself with bedsheets.

When I told him not to lose hope and to think about how his suicide would affect his son, he replied that God would take care of the boy.

A few days before my visit to Krome, I stopped by the office of the Florida Immigrant Coalition, one of the state’s leading advocacy groups on behalf of detainees, and met with its political director, Thomas Kennedy, who was raised in Argentina, and a membership organizer, who asked to be identified only as Enrique, due to concerns over his immigration status.

One of the things that made Florida especially terrible for detainees caught in the maw of the immigration-industrial complex is that virtually all state facilities for detainees have been privatized and turned over to profit-seeking, cost-cutting, politically connected firms. These outfits enjoy great influence with the legislature—it’s how they lined up their contracts in the first place—and as a result face vanishingly little public accountability. For example, the top state lobbyist for Boca Raton-based GEO Group—which has been embroiled in multiple scandals stemming from the appalling care at its 13 detention camps—is a man named Ron Book. His daughter, Lauren Book, is a Democratic state senator. GEO Group’s Washington lobbyist is Brian Ballard, who was based in Florida until Donald Trump won the presidency; in 2017, Ballard swiftly relocated to the capital. Last year, Politico dubbed him “The Most Powerful Lobbyist in Trump’s Washington.”

GEO Group runs the Broward Transitional Center, which houses most female detainees in south Florida but some men as well. ICE officially runs Krome but has privatized almost all services, including security, health care, phone and video calling, and the commissary, where detainees are gouged with prices that no one in the free world would pay—about $17 for a tube of toothpaste, for example.

Krome was previously operated by Doyon Ltd., an Alaska Native-owned company, and New Mexico-based Akal Security, but their $4 million-a-month contract was not renewed, due to a pattern of detainee abuse. Now AGS, a wholly owned subsidiary of Akima LLC, another Alaska Native corporation—which “prides itself on total detention management solutions,” and whose team includes “senior staff” from ICE—supplies armed guards, transports detainees, and provides other services on a ten-year contract.

The Florida legislative session had just ended when I visited the Florida Immigrant Coalition’s office. Kennedy wearily characterized the session as a complete disaster for immigrants, and Floridians generally. State legislators, led by Republicans, voted to arm teachers and redirect $140 million from public schools to charter schools; used the so-called sprinkle budget—discretionary funding available to lawmakers—to rain money into GEO coffers; and, naturally, approved a severe anti-immigrant measure.

Soon after Donald Trump’s January 2017 inauguration, he issued an executive order that threatened to cut federal funding from “sanctuary jurisdictions.” Less than a day later, Cuban-American Mayor Carlos A. Gimenez made Miami the first—and, thus far, only—major city to voluntarily capitulate to Trump’s edict.

In February 2017, Gimenez also turned Miami into the first city to agree to honor “Immigration Detainers.” These documents are nonmandatory requests from the federal government to local law enforcement agencies to hold someone whom ICE suspects of violating civil immigration law for 48 hours past the time they should be released from custody, for instance, if their case is dismissed or if they post bail.

A report by the Florida Immigrant Coalition, the Community Justice Project, and WeCount! has documented the fallout from this punitive turn in state immigration politics. One man, sentenced by a county court to a single day of probation, was turned over to ICE and put into the deportation pipeline. Others have been turned over for charges as minor as failing to obtain a driver’s license. “Regardless of the severity of the local criminal charge, it must be stressed that individuals in pretrial detention have not been convicted,” the report said. “98% of individuals with detainers released to ICE by Miami-Dade had never had a previous offense.”

The warrants service officer program, another Florida innovation, was cooked up by Pinellas County Sheriff Bob Gualtieri. It deputizes police officers to serve ICE warrants at county facilities. “They are trying to fuse local law enforcement and detention, and often for dumb reasons like driving without a license or smoking a joint or running a stop sign or loitering or pissing on the street,” Kennedy said. “They get a 48-hour detainer hold, and then ICE or, in Pinellas County, cops pick you up, and you end up getting deported.”

Around 8:30 one morning during my tour through Florida’s immigration feeder system, I got dropped off at the Miami area’s major ICE “substation” in Miramar, Florida, to meet Bud Conlin, a FOMDD founder. This bureaucratic terminal, about 19 miles north of Krome via the Ronald Reagan Turnpike and near a gigantic new FBI field office, is an intermediate step for many immigrants at various stages of the bureaucratic process that will determine their futures.

It was a brutal if typically hot June morning, and the temperature had already climbed into the mid-80s when I arrived. The facility serves a huge area from Fort Myers to Key West. ICE can randomly demand that anyone within this enforcement boundary turn up to be interviewed—once, twice, or five times a week if a functionary feels like it—in order to prove they have not violated immigration law. For many immigrants, the Miramar Substation represents an initial step into the deportation pipeline. “Anyone who reports here is legal until they’re not,” Conlin told me. “And they’re not legal when some bureaucrat at a desk says, ‘I think we can deport you. Stand up, you’re being detained.’ Then you’re put in handcuffs and taken to Krome or the Broward Transitional Center.”

A chubby, bearded, infectiously upbeat man dressed in shorts and a t-shirt, Conlin is a retired school principal from northern Michigan. He and his wife, Jeanne Conlin, moved to Florida in 2012 and the following year visited Krome through a church program. Conlin soon founded FOMDD, which organized a visiting program at Krome, and he and the group’s staff and volunteers have met with more than 1,000 detainees since. “We’d talk to people at Krome and they’d get released and after three or four months they’d be back,” he told me. “They’d say they got called into Miramar and sent back. That’s when the light bulb went on and we realized Miramar was a feeder into Krome.”

FOMDD and other advocacy groups arrange a weekly gathering at Miramar—Conlin’s first venture into civil disobedience since the Vietnam era. He was sitting out front with a group of about two dozen activists who advise immigrants called in by ICE—people start arriving around 5 a.m., and if you don’t get there early, you can wait in line all day—and their families. They also hand out hats and provide coffee, water, and other refreshments. “This is not how I expected I’d be spending my retirement,” Conlin’s wife, Jeanne, deadpanned.

The scene that unfolded before me was cruel and chaotic. More than 100 people were standing in line 30 minutes before the substation opened its doors. Some stood under flimsy tarp that, under pressure from activist groups, the city of Miramar had installed, because ICE refused to, just as it refuses to provide water to the detainees it compels to stand for hours in the blistering heat. There are no portable toilets, and only two inside when detainees get that far. The interviewees and their family members have to walk more than ten minutes to a Publix supermarket and use a bathroom there.

While Conlin and I talked, a Guatemalan man carrying his young daughter on his shoulder stopped by to ask for advice. “He says he’s been here two years, and his paperwork is in process, but ICE told him to come in anyway,” Conlin, who had handed the man a bottle of water and a bag of potato chips, told me. “He could be working, but he’ll be standing in line all day. Some of these people will be told they need to come back again tomorrow or go to another ICE facility.”

And such harassment only marks one facet of the systemic cruelties of the detention system in Florida. Conlin told me a “common thread” had emerged from the countless interviews he and FOMDD’s volunteers had conducted with Krome detainees: “People get rousted 25 times a day, when they are sleeping, before breakfast, after breakfast, they get grabbed from the cafeteria, it happens all the time,” he said. “Some people get put into solitary on purpose, because they can’t take the stress from the daily routine.”

“You can get in for breaking a razor, and the ones they give out are cheap, so that’s easy to do,” he continued. “Or you can get into a confrontation with a guard, and that’s easy, too, because many guards are looking for a confrontation…. That can be a serious mistake, because people who go into solitary often develop—and some already have—serious mental problems. The danger is especially high for people who go in repeatedly, because first offenses are for a few days, but the time of punishment escalates from there. I tell them, ‘You might be OK for a few weeks, but if you get put in for longer, you may lose your mind.’”

In one sense, all the key features of south Florida’s immigration police state have been hiding in plain sight for a generation. Krome has been a notoriously cruel and corrupt institution since the late-1990s. Jack Blum, a Washington lawyer and former Senate investigator with long experience in Miami, told me that back then wealthy immigrants held at Krome could buy their way out by hiring the right lawyer. Conversely, undocumented immigrants could get sent to Krome if they had the wrong local enemies. Blum told me about a Russian who moved to Miami and ran into trouble with Russian organized crime, which has a huge local presence. The mobsters knew he was in the country illegally, notified ICE, and the Russian disappeared.

In recent years, alleged abuses have multiplied as the wave of mass deportations in the region has grown. A 2015 story in the Miami New Times, based on hundreds of pages of files on detainee complaints submitted between 2012 and 2013 and obtained through a Freedom of Information Act request, found multiple cases of detainee abuse. In one, a mentally ill man in his twenties briefly took control of a golf cart that guards use to drive around the facility. Six guards pulled him from the cart and beat the man, who had to be sent to a hospital for treatment. A few days later, detainee Noel Covarrubia saw the man back at Krome. “His lips were badly swollen and broken open, and one of his eyes was still bulging,” the newspaper reported.

In 2016, Jose Leonard Lemus Rajo, a 23-year-old Salvadoran who overstayed his visa, died less than three days after his detention at Krome. ICE blamed his death on “alcohol withdrawal,” but Krome apparently took few steps to diagnose and treat his symptoms while he was detained. “ICE detainees’ serious physical and mental health issues are routinely ignored,” Jessica Shulruff Schneider, an attorney at Americans for Immigrant Justice, said at the time. “Detention can too often mean a death sentence.”

I visited Krome on the evening of Thursday, June 6. Conlin couldn’t go along, because ICE barred him and Thomas Kennedy for participating in the protests against the brutal conditions at Miramar. But he arranged for Mustelier, FOMDD executive director Karina Livingston, and volunteer Marisa Baylon Guillen to accompany me and conduct interviews as well.

AGS’s private security guards, sporting revolvers and bulletproof vests, waved us through the gate after checking our IDs and searching the trunks of our cars. We entered the main building and filled out a series of forms. We were processed well in advance of the start of visiting hours at 6 p.m.

I met with two other detainees in addition to Omar, the Middle Eastern man, who were housed in KTU. Like him, my other informants were waiting out indefinite bureaucratic delays in their cases. Abshir, the Somali detainee, was one of the so-called Somali 92—a group of deported Somali citizens lacking proper documentation flown out of the United States under orders of deportation in 2017. They were supposed to be returned to their home country, which is wracked by violence and famine and has had no functioning central government since 1991. (The chaos there stems in part from the country’s onetime status as a pawn in the U.S.-Soviet Cold War.) The plane only got as far as Senegal, where it turned around due to logistical problems. The Somali 92’s 5,000-mile round trip ended in Miami, after a 23-hour stop in Dakar, Senegal’s capital, where ICE left them shackled as they had been throughout the trip. When they were finally unbound, the plane was covered with human waste. (ICE has denied the allegations of abuse and unsanitary conditions brought by the 92 Somali men.)

Abshir came to Minneapolis, where his remaining family and friends still live, as a refugee in 1997. He’s now being held in KTU and fed a steady stream of medications, he said, ostensibly because he’s depressed, though I saw no sign of it when we spoke. He was amiable, charming, and intelligent and asked me to send self-help books by John C. Maxwell, such as The Power of Your Potential, because he wants to study and learn during his detention, and work hard when he gets out.

The other FOMDD volunteers in my group returned from their detainee interviews with distressingly similar stories. One detainee, whom I’ll call Santiago, was a Colombian national who has been in the United States since at least 1993. He’s been detained for over 32 months due to a burglary charge and said, credibly in the view of Mustelier, who interviewed him, that police beat him up and broke his nose while he was handcuffed. Santiago, who is held in KTU, also suffers from bipolar disorder. Like Omar, the Middle Eastern detainee with whom I spoke at length, Santiago reported that his psychological interviews have gone well at KTU, but that he’s frequently on edge due to the severe overcrowding and lack of privacy at the Krome facility.

While Krome has attracted relatively little national press coverage and Miramar not a great deal more, there has long been an ongoing uproar over conditions at the Homestead Temporary Shelter for Unaccompanied Children. It’s also near Miami and is run for ICE by a few private contractors. Presidential candidate Elizabeth Warren traveled to Homestead, just prior to a televised Democratic debate, but was not allowed in.

The media attention and outrage over Homestead is entirely understandable. Under the landmark Flores settlement, approved in 1997 to resolve a class-action lawsuit on behalf of immigrant children detained by the former Immigration and Naturalization Service, the U.S. government has generally been limited to detaining immigrant children for 20 days and then releasing them to a guardian or family member. Trump has sought, thus far unsuccessfully, to override Flores and hold families in detention until the conclusion of their immigration hearings. Meanwhile, ICE is allegedly violating the provisions of Flores on a routine basis in Florida and holding kids for 30 to 160 days. Children who turn 18 at Homestead get a special birthday present from ICE: Having now attained “adult” status, they are moved to Krome or the Broward Transitional Center and put in the direct deportation pipeline.

Because there’s so much outrage justly focused on the abusive conditions at detention centers housing children separated from families, the status-quo maltreatment of adult-age detainees, which involves less visible and high-profile brands of abuse, tends to escape sustained public attention. That’s especially the case for immigrants suffering mental illness, which tends either to involve silent and corrosive conditions such as depression and suicidal ideation, or to render its sufferers stigmatized as erratic, potentially dangerous individuals who must be isolated from the general detainee population on grounds of public safety.

Homestead is entirely of a piece with the cruelty and abuses that immigrants are subjected to at Krome and the other detention camps in ICE’s nationwide network. “Focusing on Homestead is misleading, because it suggests that if we just fix abuses at the margins, the system is OK,” Enrique, the Florida Immigrant Coalition staffer, told me. “Our goal is to shut it down.”

* A previous version of this article stated that Elizabeth Matherne works at the Southern Poverty Law Center. She is a former employee of the organization.