Svetlana Alexievich was born in 1948 in Ukraine, three years after the end of World War II. Shortly afterwards, her father moved the family back to his homeland, Belarus, where Alexievich would grow up to become one of the country’s most celebrated writers, winning the Nobel Prize in Literature in 2015. These childhood years in a small Belarusian village, she has recalled, included many nights listening to adults tell stories about the war: “In the evening, sitting on benches, people talked, and we, the children, listened, of course … this made a big impression on me. A much bigger impression than books.” Later in life, she would turn stories like these, casual recollections of unthinkable atrocity, into some of the greatest works we have about the twentieth century.

A hallmark of Alexievich’s oral histories is bewilderment. The people she interviews have had to learn to cope with unimaginable, unprecedented moments of disruption: Chernobyl, the collapse of the Soviet Union, and of course—World War II. But Alexievich’s subjects remind us that before these events became historic, they were just confusing: “I couldn’t quite figure out,” a professor tells Alexievich, “how it was possible that in our garden, where a samovar was still standing on a little table from the evening before, there were suddenly saboteurs!” In essence, Alexievich writes about people who, like herself as small child in Belarus listening to stories about fascism, do not understand what is happening.

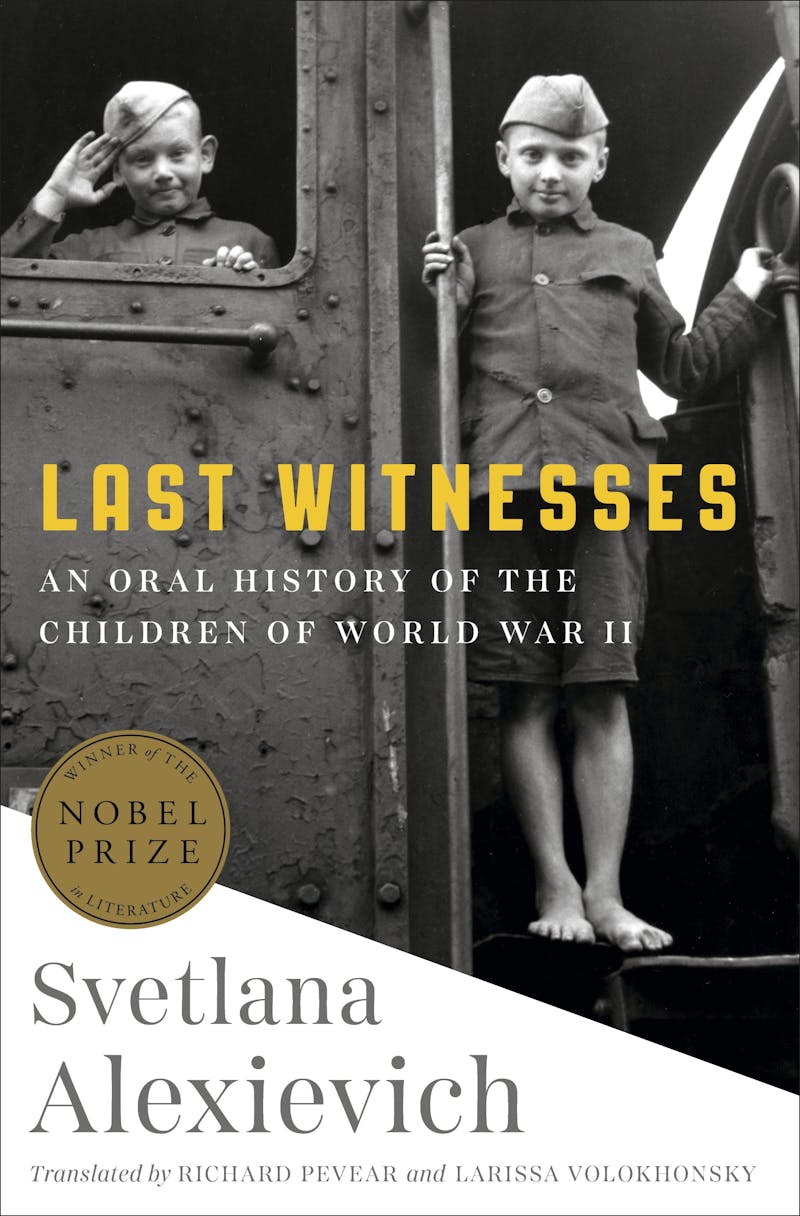

The latest of her books to appear in English puts the perspectives of actual children center stage. Last Witnesses: An Oral History of the Children of World War II collects intimate, unguarded testimonies from ordinary people (railway workers, gym teachers, musicians) as they reflect on their childhood memories of the war: They remember being at the circus on the day the war broke out and how giddy they were afterwards, even as people shouted “war” around them on the streets. They remember animals and insects and other small things that loom large in a child’s line of sight. “I remember being envious of the bugs,” one tells Alexievich, “they were so small that they could always hide somewhere, crawl into the ground.”

Last Witnesses, in its attention to the most unsuspecting of bystanders—children—is arguably a guide to all of Alexievich’s writing. Children have small worlds; very few people exist for them outside of their family. In this way, they naturally live like adults in times of crisis—with tremendous focus on the people they love. In Alexievich’s books, people retreat inward to survive and anything outside of the most intimate of spaces distorts into indiscernibility. People water plants in homes they know are about to be bombed, boil beetles to make soup for their children. Anything beyond that is a mystery, until we get to the next story, the next interview.

When the Nobel committee awarded Alexievich the prize, they praised her for what they called her “polyphonic writings”—the combination of distinctive voices, as she allows one person after another to tell their stories. Critics have long struggled to describe this style, marked by a kind of literary editorializing of first-person interviews. Is it journalism? Oral history? Maybe “documentary literature”? While the translators of this volume, Richard Pevear and Larissa Volokhonsky, call it “oral history,” the original Russian title calls the interviews “unchildlike lullabies.” Alexievich has written about her search for new forms, new ways of telling stories that stretch the limits of human comprehension. She credits the Belarusian novelist Ales Adamovich, who called his own books “epic choruses,” with helping her settle on a method. Indeed, at time when we debate the effectiveness of images, viral videos, and body cameras to convey the violent outrages of our present moment, Alexievich’s book, and the “epic chorus” of voices it contains, is a bracing reminder of the enduring power of the written word to testify to pain like no other medium.

Fittingly, one of the recurrent themes of Last Witnesses is how war mangles the experience of childhood, turning what were once toys (airplanes, horses) into engines of terror, and pets into food. Last Witnesses is at its most bracing when it captures the minds of children struggling to adjust to their new realities. As one survivor recalls to Alexievich: “I was very surprised that the young fascist officer who moved in with us wore glasses. My idea was that only teachers wore glasses.” We are reminded reading Last Witnesses just how much children observe adults, looking for answers, clues on how to react; war is for them a time of profound confusion when the rules they’ve been strictly following seem now to have never existed. In one interview, a survivor remarks his shock at seeing a woman undress, taking off her leggings in public so that she could fill them with buckwheat. In a particularly difficult-to-read episode, we hear about a three-year-old girl who finds a “pineapple” and starts playing with it until the grenade explodes.

World War II is known in the former Soviet Union as “the Great Patriotic War,” and the exploits and heroism of men are central to memory of the war there. In her first book, The Unwomanly Face of War, Alexievich sought to undo this imbalance by interviewing the women who lived through World War II, from nurses to snipers. Likewise, in Last Witnesses, women, or specifically mothers, are central to children’s memories of the war. With men at the front, mothers become larger than life for their children; “Mama was my world. My planet,” one interviewee tells Alexievich. When mothers die in Last Witnesses, we see new families spontaneously form, new mothers appear. In one interview, a woman recounts losing her mother and crying about it to a teacher: “The teacher shook me by the shoulders to calm me down, and I shouted, ‘Mama! Where’s my mama?’ Finally, she pressed me to her: ‘I’m your mama.’”

Childhood was a hallowed time in the Soviet imagination. Children were considered unmolded clay that could be shaped, through summer camp and brightly colored books about cotton production, into the new Soviet subject. One of the most storied Soviet institutions for children was the Young Pioneers, the communist counterpoint to the Boy and Girl Scouts. A Russian woman once scolded me for making this comparison; she scoffed that girl scouts just baked cookies while Pioneers learned to start fires and climb mountains (I had to confess that we didn’t bake the cookies, just sold them). After the Pioneers came the Komsomol (the communist youth league), and potentially, for especially active members, official roles in the Party leadership.

Children’s literature in the Soviet Union was a serious genre for this reason, and many of the country’s most acclaimed writers and illustrators were tasked with writing it. In one story, titled “Red Neck” (in a reference to the red scarf the Pioneers wore), a little boy refuses to take his off his Pioneer scarf even when faced with a charging bull. Just as The Unwomanly Face of War undid patriarchal narratives about war, so too does Last Witnesses revise the idealized vision of a patriotic childhood that permeates post-Soviet nostalgia to this day. The book presents a generation of young people whose experiences of the war were not defined by ideology or national pride, but rather through personal loss and family trauma; in one story, someone tells Alexievich that he can’t recall Stalin’s speech, but he can remember himself and his brother hiding in a ditch, making nooses for themselves.

Reading Alexievich, it was difficult to not think of our own child witnesses at the southern border who everyday are facing unsanitary conditions, irreparable emotional trauma, and, as we saw in the drowning of Óscar and Angie Ramírez, even death. In one of the interviews in Last Witnesses, a woman named Emma Levina, who was 13 during World War II, reflects, “Now I think: what a terrible time, but what extraordinary people.” Will migrant children remember us, the adults in charge of their safety, in the same way? Alexievich’s book is a reminder that children survive, they grow up, and they do not forget. They are the first and last witnesses.