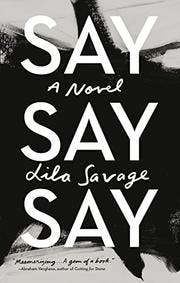

Kirkus Reviews recently called Lila Savage’s debut novel Say Say Say, about a care worker who tends to a middle-aged woman with a serious brain injury, “tedious,” condemning her as “an author who is maybe a little bit too in love with her heroine, not to mention a bit too in love with her own voice.” Kirkus’s anonymous reviewer seemed particularly displeased by the heroine Ella’s healthy self-esteem, taking aim at a metaphor Ella uses for her own beauty: “like a secret lover, she stroked it softly like a young boy watching television, one hand tucked into his pajama bottoms, fondling his small, flaccid treasure.”

The focus on this masturbatory image sends the message that Say Say Say is an indulgent rehash of ordinary life by somebody who likes herself too much to write serious literature. But this observation is all wrong. What Savage has created is extremely rare in the pages of contemporary fiction: a millennial woman narrator whose mind is not broken. Women with psychologies bent out of shape are the rage right now, delivering jagged nihilism through pursed lips in books like Sally Rooney’s Conversations With Friends, Ottessa Moshfegh’s My Year of Rest and Relaxation, Rachel Cusk’s Outline trilogy, Nell Zink’s The Wallcreeper, and many more. The protagonists of acclaimed women’s fiction these days tend to be glamorous, self-centered, and cynical.

In contrast, Ella is a young woman, knocking on thirty, who spends months taking care of Jill—a thankless, arduous task that could not be more unglamorous, self-effacing, and heartfelt. Savage weaves into this a second story, about Ella’s complicated, quasi-romantic relationship with Jill’s husband, Bryn. Savage takes ordinary human suffering as her subject, told by a pretty woman who does not hate herself. In so doing, she has staged an overdue intervention into the fiction of female interiority, to establish a signpost for new directions in literature about young women.

America’s population is aging—10,000 people turn 65 every day, while their offspring or other relatives increasingly live too far away to take care of them at home. Care for the chronically ill and elderly is in crisis, just as all health care is in this country, and remaining in one’s home into old age is less and less of an option. Residential facilities are often the only financially viable choice for families trying to support vulnerable adults.

This background is key to Savage’s novel, because it frames Ella’s occupation as an unusual calling—a caregiver who is neither family nor friend, but intimately involved in the denouement of Jill’s life, whether she is wrestling Jill when she tries to escape the house, or trying to brush Jill’s teeth despite her shrieks of anguish. The entire plot of Say Say Say is defined by care work, beginning with Ella’s interview with Bryn and ending with the day Jill moves to a care home. Not much happens in between except thinking. Page after page, we simply sit with Ella as she sits with Jill. And yet the book is never dull, because Savage continually draws and redraws her heroine’s emotional attachments like an ever-evolving diagram.

Caring for adults is a kind of endless private drama. Savage gazes intently at Ella’s labor, both emotional and literal, intricately describing the way she steps “in and out of grief” so that she can “sample it on demand.” It sounds hard, and is, but “the poignancy was among the few rewards of the job,” which is why Ella doesn’t shut herself off from the pain she encounters. She has learned that intense feeling, even when agonizing, is a gift: “she was grateful to have this lesson at so little personal cost, because the tragedy belonged to someone who’d begun as a stranger.”

Passages like these are surgically well-expressed. As Ella settles into her new job, Jill doesn’t particularly seem to like Ella, but then again nothing she says can be taken seriously, because her cognition is so damaged. (The title comes from the mutterings of Jill, who speaks only in broken phrases that call back to her lost identity. “Say say!” Jill says.) Ella is unsure how to react to that paradox: “It was Jill’s weary sternness that read as the clearest evidence that she was a mature person enduring hardship,” Savage writes, “and Ella’s disinclination to acknowledge those cues seemed somehow invalidating.” In other words, returning Jill’s dislike would be to care for her poorly, but ignoring it is akin to dismissing the only bit of communication skills left to her client. It’s an insoluble moral problem, hovering over a simple bit of conversation.

Slowly, as Ella’s mind unfurls before the reader, we learn how this dense, difficult work has illuminated corners of her soul—the place where love touches hate, where language has broken down and only feeling remains—that usually stay dark.

In 1931, Virginia Woolf gave a speech on the topic of “Professions for Women.” It was about earning a living as a writer, and the Victorian model of self-sacrificing domesticity she had to overcome. She called that model woman “The Angel in the House,” after an 1854 poem by Coventry Patmore celebrating his demure, submissive wife. “My dear, you are a young woman,” the Angel whispers to Woolf: “Be sympathetic; be tender; flatter; deceive; use all the arts and wiles of our sex.” Woolf describes herself murdering the Angel—catching her by the throat, to be precise—so that she herself can flourish beyond her grasp.

Now, there is no universal expectation that a woman should stay at home and prioritize everybody else’s well-being over her own. The modern creative woman’s relationship to domestic labor is completely different: in many instances, richer women pay poorer women to do their house- and care-work for them, without giving them any of the high praise Coventry Patmore gave his wife. Domestic labor still exists—it has just been sliced out of the lives of well-off American women, and therefore concerns them less obviously.

In writing the character of Ella, Savage offers us a political argument: that women who labor in the home and principally care for others can grow in intellectual value because of, not in spite of, their occupations. Savage rejects Woolf’s either/or model. She suggests that stigmatized “women’s work” can be a place for self-esteem to bloom. Like Woolf, Ella has chosen a career that does not resemble that of her peers. Unlike Woolf, she is able to locate the parts of traditional women’s work that bring reward, both material and spiritual, and she refuses to be haunted by that choice.

All this makes Ella’s contentment—with her beauty and with her work—quite radical. She revives the Angel in the House by pointing out that all she was missing was autonomy, not a lack of household chores. In this way, Savage creates new configurations of women’s self-love, based on human connection. One of those women may be damaged by brain injury and unable to speak, but there is still enough care to keep the flame alive.