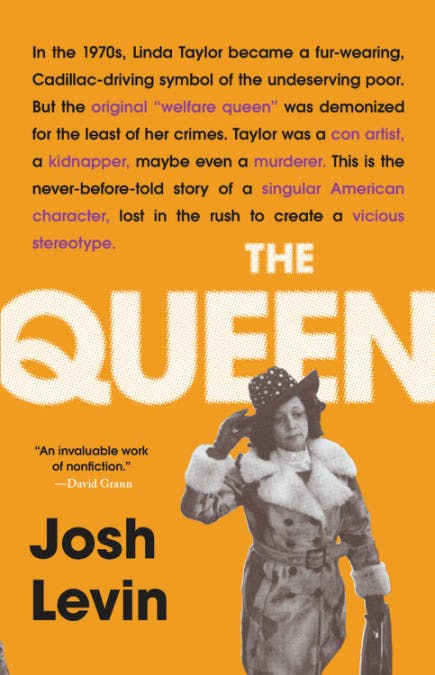

“No one’s life lends itself to simple lessons and easy answers,” Josh Levin writes in the opening pages of his new book The Queen, and Linda Taylor’s “was more complicated than most.” As his book goes on to prove, that is in many ways an understatement. Linda Taylor may not be a household name, but anyone in this country is likely familiar with a different moniker she was given: the welfare queen.

As Ronald Reagan and other politicians ginned up anti-government and anti-poor resentment in the 1970s and ’80s, the welfare queen stood in for the idea that black people were too lazy to work, instead relying on public benefits to get by, paid for by the rest of us upstanding citizens. She was promiscuous, having as many children as possible in order to beef up her benefit take. It was always a myth—white people have always made up the majority of those receiving government checks, and if anything, benefits are too miserly, not too lavish. But it was a potent stereotype, which helped fuel a crackdown on the poor and a huge reduction in their benefits, and it remains powerful today.

In fact, the welfare queen trope has made a comeback in our current politics. It appeared when former Speaker of the House Paul Ryan decried inner city residents “not even thinking about working or learning the value of the culture of work.” It courses through President Trump’s rhetoric as he’s pushed for work requirements in a variety of public programs, arguing, “We must reform our welfare system so that it does not discourage able-bodied adults from working.”

And it was all based on one arguably minor facet of an actual woman’s complex life: her use of fake names and fake sob stories to get public benefits. Meanwhile, it ignored both the racism and sexism she faced throughout her life, as well as the far more horrific crimes she perpetrated—crimes that were simply of no political use to the men who wielded her story like a weapon. The strength of The Queen lies in Levin’s meticulous scouring of the historical record to paint a picture of a woman who was infuriatingly difficult to pin down during her lifetime, resurrecting a biography of the person who would become the ur–welfare queen. By examining her reality, we can finally question the very concept of a welfare queen and deconstruct a myth spun out of selective details.

Linda Taylor was born in 1926 as Martha Louise White in Golddust, Tennessee to a white woman named Lydia Mooney White. Her father was black. She had been conceived in Alabama, where, at the time, sexual relations between white and black people were illegal and punishable by prison time. The family frequently lied about her race, as telling the truth could have made her mother guilty of a felony.

Martha grew up the child of itinerant sharecroppers who made little money and were often devastated by droughts and floods. On top of the financial deprivation, she was often made to feel like an outsider in her own family because of her race, never allowed in her uncle’s home and kept out of family functions. She was expelled from an all-white school at age six and didn’t make it past the second grade.

She gave birth to her first child in 1940 around the age of 14 and would go on to give birth to four more over her lifetime. It was around then that she left home and began her own itinerant lifestyle, moving first to a mostly black neighborhood in Oakland, California. She quickly accumulated a criminal record mostly thanks to local laws meant to control “loose women” and the spread of venereal disease; her first charge was in Seattle for disorderly conduct in 1943, when she was branded “a promiscuous woman,” Levin reports. (Her male partners were never charged.) While she did appear to make attempts at formal employment, she was also at a disadvantage. Racism had limited her education, and racism also limited her employment opportunities, even if she often leaned into racial fluidity or even assumed a white identity.

She certainly perpetrated welfare fraud, showing up to aid offices and describing hardships she hadn’t experienced and children she didn’t have to get expedited checks from the Aid to Families with Dependent Children (AFDC) program, the cash welfare program now known as Temporary Assistance for Needy Families. Her system “preyed on the sympathies of overworked bureaucrats and exploited rules designed to help the vulnerable and destitute,” Levin reports. “Most of the time, it worked.” She used a rotating cast of aliases to get those checks, as well as to perpetrate other frauds in other programs and private systems like life insurance.

She may very well have also suffered from mental illness. At her first trial over welfare fraud, her attorney asserted that she “was incapable of knowing whether or not she was telling the truth” and had her evaluated by psychiatrists. In 1978, three of her lawyers said the same and two psychiatrists found she was “psychotic.” A public defender representing her in 1994 similarly told a judge she couldn’t partake in her own defense because “she was vague, tangential, and related facts which were extremely improbable, if not impossible.” A series of experts examined her over the next years and couldn’t make firm conclusions about her mental health, but she reported hearing voices and having visions, had trouble with abstract thought, and appeared to be delusional. Her behavior certainly seems to have followed clear and disturbing patterns. Every chance she got, she used fake names to sign up for public benefits, even when it led authorities right back to her. She did not seem capable of telling the truth, even in small matters like her own name.

In September 1974, the Chicago Tribune ran a story about Taylor’s welfare fraud, launching her infamy. While that story focused on the lack of a crackdown on such cases overall, it quickly caused a national sensation focused on Taylor herself. United Press International ran a story shortly after the Tribune’s in more than 11,000 newspapers across the country declaring that “For Linda Taylor, welfare checks are a way of life.” The papers wrote their own headlines, and it was in the Democrat and Chronicle in Rochester, New York that she was first dubbed the “welfare queen.”

She wasn’t the first woman to be crowned with the epithet. But, as Levin notes, Linda Taylor “was a real person, not some anonymous, maybe even fictional character in a newspaper or magazine. She could be found, and she could be punished for what she’d done.” She imbued a shadowy idea with a human shape. “Taylor’s mere existence gave credence to a slew of pernicious stereotypes about poor people and black women,” Levin writes. “If one welfare queen walked the earth, then surely others did, too.”

Linda Taylor quickly became a political tool wielded for purposes far beyond the contours of her misdeeds. The amount that Taylor actually filched from the AFDC program was much less than authorities claimed. Press reports included unsubstantiated assertions that she raked in tens of thousands of dollars. Reagan repeatedly cited a six-figure income. In reality, a grand jury indicted her in 1974 for receiving payments adding up to a grand total $7,608.02, later increased to $8,865.67. And yet, Cook County spent at least $50,000 to convict Taylor, not to mention what it spent to imprison her nor the resources expended to build the case against her.

Her story, and the eventual case against her, fueled a crackdown in the Illinois legislature on supposed welfare fraud, leading to an 88 percent bump in the budget for the designated committee and a partnership with the Chicago police. The Public Aid Department had experimented with offering amnesty to potential welfare fraudsters, but that was ended and, thanks in large part to Taylor’s case, the focus turned to going after them like criminals. Three-quarters of welfare fraud cases were referred to law enforcement by 1979, up from 28 percent in 1970. The department began systematically auditing the AFDC and other programs. Lawmakers even set up an anonymous hotline to receive tips about potential cheats. It would steadily take in more than 10,000 reports a year.

The courts followed suit. In the late ’70s, “the Cook County courts were in the grip of a kind of anti–welfare queen hysteria,” Levin reports. They went after other so-called welfare queens aggressively, keeping them locked up on $100,000 bails and pushing to quickly get them prison time.

The politician to make the most hay out of Taylor was Ronald Reagan. Reagan’s crusade against welfare began early. In 1971 he called it “a cancer eating at our vitals.” As California governor, he tightened eligibility rules, reduced benefits, and implemented work requirements. But as he campaigned for president for the first time in 1976, he started telling the story of a woman in Chicago who, he said, used 80 names, 30 addresses, and 15 phone numbers to collect benefits that earned her “$150,000 a year.”

While Reagan never used Taylor’s name, nor even directly racialized her, he didn’t need to. The “woman from Chicago” who wore furs and drove a Cadillac while receiving government checks was clearly black to his white supporters. And while the AFDC’s caseload never became majority black—60 percent of AFDC families were nonblack—the face of poverty in popular media had become black, allowing Taylor to represent a group toward which white Americans were growing resentful. Without articulating explicit racial animus, Reagan conveyed a story that spoke to people’s racist ideas about public benefits and lazy black people.

In his failed first go at the White House, Reagan never used the phrase “welfare queen.” But he did adopt it afterward. Taylor’s story figured prominently in his second, successful run for president in 1980; he kept using the story of the “woman in Chicago” collecting checks under hundreds of aliases even after Taylor had already served her time in prison for that very fraud and been released.

Once in the White House, Reagan’s tall tales were used to justify real-life changes. In his first inaugural address, he promised to reduce the federal budget by getting rid of supposed fraud in public programs, including “tighten[ing] welfare and giv[ing] more attention to outside sources of income when determining the amount of welfare that an individual is allowed.” Eventually, Congress would pass $25 billion in cuts to programs that helped the poor. An estimated 408,000 households were cut off from AFDC, while millions more saw their benefits reduced.

Then as now, the actual deprivation facing people who turn to cash assistance never generated the kinds of headlines or national outrage that Taylor’s outlandish story did. As Levin notes, in 1974, 12 percent of the country lived in poverty, surviving on a little over $5,000 a year for a family of four. Such a family could expect just $3,456 a year from AFDC to supplement its meager income, an amount that went without an update for years while inflation soared.

And the biggest problem with the program was not that people were cheating the system with elaborate, Taylor-style schemes, but that the system was cheating them. An in-depth examination of AFDC in the Chicago area in 1960 found that the biggest problem was public “hostility to this most disadvantaged segment of our population.” A 1970 Associated Press report found that 39 states were “illegally denying the poor either due process or deserved relief benefits.” If there was an epidemic of fraud, it was almost certainly more prevalent among white-collar people such as doctors bilking Medicaid or civil servants who collected both salaries and benefits. A 1978 federal report found that just 1 percent of the annual budget of the Department of Health, Education, and Welfare was lost to “unlawful, willful misrepresentation (fraud) or excessive services and program violations (abuse).” Less than $500 million of the agency’s losses were in AFDC; most instances of people getting money despite being ineligible were honest mistakes.

While Taylor and her story were used to foment hatred against welfare cheats, welfare fraud was almost certainly the least of her crimes. “In 1967, she was charged with kidnapping and wasn’t prosecuted for it,” Levin reports. “In 1975, she was suspected of murder and wasn’t questioned about it. In 1977, she was sentenced to three to seven years in prison for stealing public aid money and lying about it to a grand jury.”

Levin makes a convincing case that she was indeed a murderer. She befriended a sick woman named Patricia Parks who then died “under suspicious circumstances” in Taylor’s care, Levin reports. One of her husbands, Sherman Ray, was shot by one of her cronies, and his family accused her of being involved, especially given that he had taken out two life insurance plans shortly before his death, with Taylor the sole beneficiary of both. She ingratiated herself with an older woman named Mildred Markham, whom she then appears to have mistreated and held against her will, potentially killing her to also collect on life insurance policies of which she had been named the sole beneficiary. Those deaths would remain “unexplained and unprosecuted,” Levin writes. There was no flurry of press items, no lengthy police investigations, nor outrage from elected officials as there was when it came to Taylor’s welfare fraud.

She certainly was a kidnapper. She took the daughter of one of her son Johnnie’s friends and tried to keep her and give her a new name. She took her niece and threw out all her clothes, buying her a new wardrobe and moving her to a different house. She may have even kidnapped a baby from his mother’s arms in a hospital in a high-profile case that was never solved.

She also abused children, both her own and others’. Her son Johnnie remembered her “alternat[ing] between ignoring him and knocking him around,” Levin reports. In the mid-’50s she left her dark-skinned son Paul with a black couple in Missouri, and he was eventually taken out of her custody and placed in a state-run school for dependent children. Her oldest, Clifford, was mostly raised by another family and left Taylor’s care for good at the age of 14. She even used and abused her daughter Sandra’s two children, Duke and Hosa, failing to give them beds or even food while using their names to pad her welfare checks. In sum, Levin writes, “Taylor abused babies, young children, and adolescents in different states across multiple decades.”

And yet the instances of fraud, as well as burglary charges over stealing from an ex-roommate, were the only crimes for which she was ever prosecuted or convicted. Welfare fraud was the only thing for which she was widely known.

Although Levin aims to locate the real Linda Taylor in this history, Taylor as a real-life human being is absent from much of Levin’s book. Until the eleventh chapter, most of what we learn about her—beyond her recorded misdeeds—is what she looked like. “She was just over five feet tall, with olive skin and dark, heavy-lidded eyes,” he writes, describing her “vaguely elfin” face shape, thinly plucked eyebrows, pronounced Cupid’s bow, gold dental work, and her “pristine” makeup above her “fashionable and snug outfit.” Most later descriptions focus on her face and her rich, sometimes outlandish clothing—almost always including fur coats. He even typically includes a description of the car she was driving, seemingly unable to avoid the trap laid by Reagan.

In the meantime, we get in-depth looks at the lives, thoughts, and motivations of the various white men surrounding her: Jack Sherwin, the Chicago police officer who tried to nab her for welfare fraud; George Bliss, the Chicago Tribune reporter who ran front-page stories that turned Taylor into the nationally notorious welfare queen; and even Don Moore, the Illinois state senator who crusaded against supposedly rampant welfare fraud like Taylor’s.

We can’t confront the idea of the welfare queen without grappling with the real life welfare queen. Doing so lifts a three-dimensional human out of the two-dimensional figure painted by all the men who have used her as a tool for their political or personal agendas. Levin recognizes how much was piled onto her story. “She was the fall guy for everyone who’d lost his job, or had a hefty tax bill, or was angry about his lot in life and the direction of his country,” he writes. “She was someone it felt good to punish.”

This is not to excuse her behavior. No matter her background, Taylor did monstrous things while she was alive. But as Levin writes of her children, “At times, they saw themselves and their mother as victims of an unjust world. At others, they felt as though they were getting lashed around by an unstable woman’s cruel whims.” In truth, it was likely both. Life is complicated. Linda Taylor was a victim of many things, including racism, family cruelty, and possibly mental illness; she then went on to victimize a long list of people herself.

One thing she clearly was not, however, was a stereotype, and Levin’s book should warn against the use of false stereotypes about the poor, black people, and mothers. Linda Taylor was real and very complicated. The welfare queen never was.