Bulelani Mfaco arrived in Ireland in November, 2017, fleeing anti-gay violence in South Africa. He hoped to pursue a PhD in politics, find a job, and build a new life. First, though, came his asylum claim.

On his first day at Knockalisheen Center, a former army barracks two miles outside of Limerick, in the south, he walked into the sterile white room assigned to him. Fluorescent tube lighting buzzed overhead as a center employee repaired a television across from twin beds set shoulder-width apart. He felt an anxious knot in his gut. He asked the employee how long the room’s previous occupant had lived in the center. Ten years, the man replied.

“Ten years?” His chest collapsed. “Ten years of your life wasted in this place?”

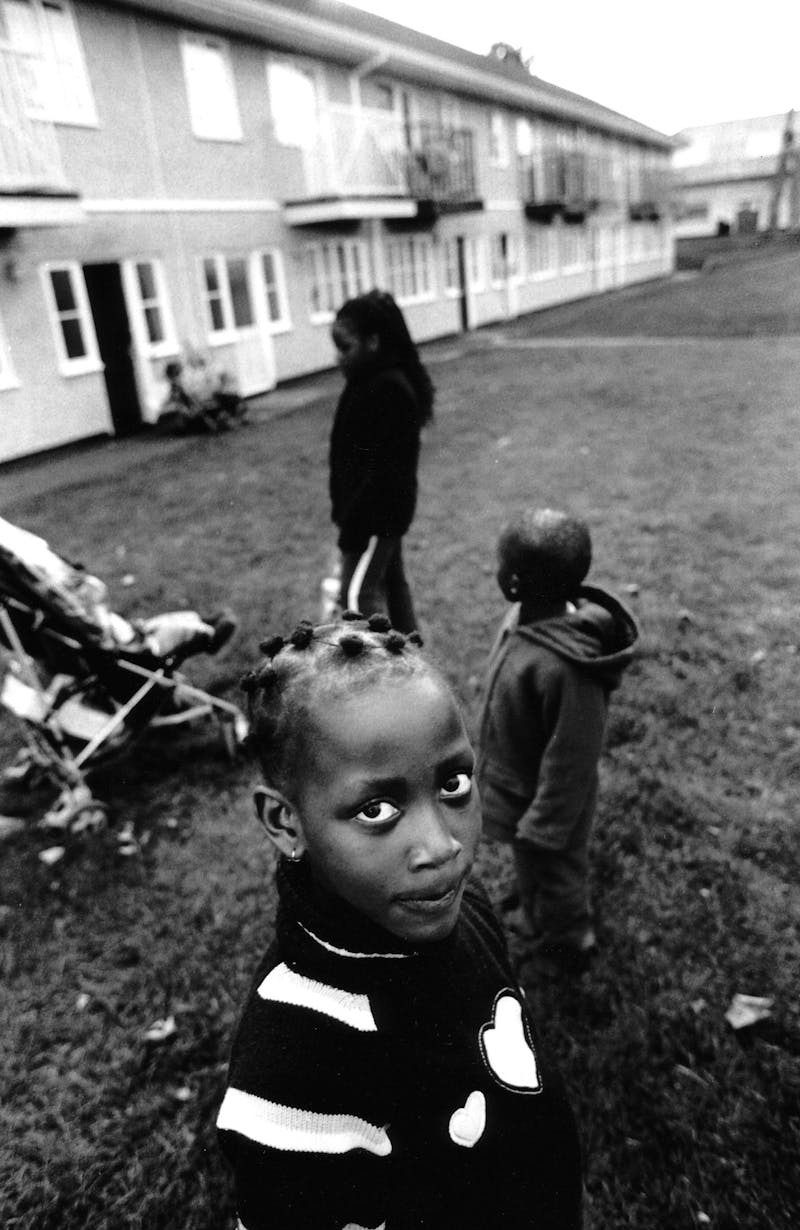

Ireland first introduced what is officially known as the Direct Provision and Dispersal system in 2000 to provide a short-term way station for asylum seekers as their claims were being processed. But as of recent reports in 2018, more than 2,467 asylum seekers had been in direct provision for at least two years and 367 had been in the system for at least five years. Some 267 have been trapped for seven years or more. The current average asylum process duration stands at 26 months—one of the longest such periods in the European Union.

The canteen at Knockalisheen Center serves breakfast at 8 a.m., consisting of cold cereal or porridge boiled in water, with coffee pumped from a commercial-grade urn. The smell is clinical, like a hospital or prison. Mfaco began to hate it after only a few weeks, along with the smells of the two-day menu rotation for lunch and dinner, at noon and five respectively: beef one day. Chicken the next.

At first, for four weeks straight, he went to the common room between meals to play pool nearly every day. But over the past 17 months, pool, like other activities, has become oppressively boring. Despite having obtained his work permit after the employment ban for asylum-seekers was lifted in 2018, Mfaco has only been able to find paid work for one hour in the last eight months. And since, like other asylum seekers, he’s barred from holding a driver’s license and the government holds his passport, he doesn’t have an identity card with which to open a bank account, anyway. He could walk three miles or pay for the bus into Limerick, the nearest town. But the small allowance he gets from the state doesn’t cover much. And so, like others among the 250 asylum seekers at Knockalisheen, many days he just waits in his shared room in the single men’s block until the canteen doors unlock again.

“It’s a prison,” Ruth, a 26-year-old former asylum seeker from Zimbabwe, told me. (She asked that The New Republic protect her identity.) It’s an apt comparison. Knockalisheen is administered by an American company better known for catering U.S. prisons.

Ireland’s direct provision system consists of 37 centers made up of converted hotels, hostels, and nursing homes and one abandoned holiday camp. There is also an old convent, some prefab buildings, and mobile homes. The state owns only seven of these centers, the rest privately held. And all of them are operated by private contractors.

Care for asylum-seekers has become a de facto for-profit industry. The Irish state paid 30 private companies to run the centers in 2018, most of which have incorporated and become unlimited companies, a legal corporate status that does not require the filing of public accounts, thereby shielding their profits from public disclosure. But based on the most recent Irish Department of Justice and Equality disclosures, the state is paying these companies at least $87 million.

The largest contract holder, Mosney Holidays, PLC—an Irish company—was paid $10.8 million last year to run a center for 600 asylum seekers. Mosney is followed by East Coast Catering, a Canadian food and housing provider that contracts primarily for work camps in oil and gas, mining, and industrial construction sites in Ireland and Canada. The fourth largest contract holder in Ireland is a subsidiary of Aramark, the $10 billion American company that has catering contracts with more than 500 U.S. prisons. In contrast to its American prison contracts, however, Aramark operates and fully administers three of the state-owned Irish direct provision centers, including Knockalisheen, the contract for the three centers amounting to $6.8 million in 2018. That means catering the food, hiring all center care staff, providing managerial oversight, and handling all day-to-day operation of each center. Aramark first acquired the contract for the three centers and care of nearly 800 asylum seekers in 2005, transferring all contracts to a subsidiary called Campbell Catering, Ltd. in 2018. Most companies with contracts were recruited by the Irish government to repurpose their properties into direct provision centers.

The lower the center’s operational cost, the higher the profit; the more bodies in a center, the higher the contract value. The incentives, those living in direct provision say, produce grim results.

In theory, designated canteens at all but one self-catered center supply three fixed meals a day on a 28-day menu rotation, with attention paid to any cultural or religious dietary needs. But at Knockalisheen, Mfaco said the 28-day rotation is more like a two-day sequence that the cooks supplement with a few drab additions. “You just have to shove it down your throat,” he told me. He desperately wants to be able to cook for himself—a hamburger, or lasagna maybe—but in Knockalisheen, like in most centers, residents do not have access to the kitchen. Ruth, who has been in the system for over four years after paying smugglers to spirit her out of Mugabe-era Zimbabwe and leaving a little sister behind, said she regularly goes hungry rather than eat the canteen food. “That’s how bad it is,” she said.

Mfaco’s and Ruth’s experiences of Aramark food echo reports from the United States. In March 2015, the Michigan Department of Corrections confirmed that Aramark had served inmates food previously thrown in the trash at the Saginaw Correctional Facility. On multiple occasions prisoners complained of maggots and mold in the food at Michigan and Ohio correctional facilities. In 2015, after 30 inmates fell ill from contaminated food and 19 months of complaints about maggots and rat-nibbled food, Michigan terminated its contract with Aramark and fined the company $98,000 for food shortages among other problems. Ohio fined Aramark more than $272,300 for violating the state’s standards for food at seven prisons in 2014. Every year, Aramark continues to provide some 380 million meals in 500 prisons across the United States, part of a correctional system in which the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reports inmates are 6.4 times more likely to suffer foodborne illness than those in the general population. Many state prison systems contract out to private service companies like Aramark and pay them a flat rate per meal—an arrangement that eases the state’s financial burden, but leaves those in its care at the mercy of the free market, vulnerable to inadequate oversight and pressure to produce a profit.

In November of 2018, students at the University of Limerick protested after news broke on Facebook that Knockalisheen staff had refused to give bread to a mother of three outside of canteen hours when she requested it for her sick child. “Knockalisheen centre has hit rock bottom if the needs of a child don’t matter anymore,” the mother wrote in a post. Aramark then peppered the campus with fliers defending its “quality services” and its commitment to “providing quality services which help make [asylum seekers’] lives more comfortable.”

Accommodation centers are “subject to regular unannounced inspections,” a representative from Ireland’s Department of Justice and Equality wrote in an email when contacted for comment. The contracts themselves “are awarded using a public procurement process,” and “contractors must prepare menus that meet the reasonable dietary needs of the different ethnic groups … It is a contractual obligation for accommodation centers that a 28-day menu be provided and that residents are consulted on that 28-day menu.” As for Mfaco’s experiences, “Complaints by residents may arise from time to time in relation to dietary matters and any such complaint may be brought to the centre manager. If the resident is not satisfied with the outcome, she or he may also make a complaint to RIA [Reception and Integration Agency], which will be investigated by RIA and action taken as appropriate.” A separate Department of Justice and Equality representative in October added that “over half of all residents now have access to cooking facilities.”

Residents also live in close quarters. In 2015, more than 80 percent of single residents were reported to be sharing their rooms with at least one roommate, some 1,500 sharing with at least two roommates, and at least 75 sleeping dormitory-style with four or more. In August 2017, a working group in Ireland’s Justice Department finally announced a draft proposal to regulate standards of accommodation in direct provision to a minimum 4.65 square meters of space per-resident per-bedroom, no bunk beds for residents over the age of 15, and separate bathrooms designated for family use. The recommendations have not yet been fully implemented.

Lack of privacy is a constant source of anxiety. Families live together in single rooms—multiple children and their parents all sharing the space, without a private bathroom. Single people live with strangers in close quarters. Even residents whose respective home countries were at war share bedrooms. Mfaco, despite citing anti-gay violence on his asylum application, was given an openly homophobic Albanian roommate, his bed not even a full two feet from Mfaco’s. When Mfaco came out to his roommate, the man cornered Mfaco in their shared room and growled inches from his face, “I don’t like that shit.” They hardly ever spoke again.

Such conditions are not ideal for asylum-seekers who have frequently endured mass violence, gender-based sexual violence, torture, and other state abuse, and who are up to ten times more likely than the general Irish population to have post-traumatic stress disorder. Charles, an asylum seeker from Zimbabwe who also requested anonymity, said the late-night screams of his neighbor keep him from getting any sleep. “It’s just terrible,” he said, “and no one is giving him any help.”

Staff can even enter resident rooms without permission. Residents say they might give a cursory knock before barging into their private rooms to find startled residents unprepared, even undressed. Twice, staff members have walked in on Mfaco, once in his room and once when the female center manager walked into the men’s communal showers. She immediately turned around, but Mfaco still felt violated. “My friends have never seen me naked,” Mfaco said. “But Aramark staff have.” Aramark did not respond to an initial request for comment and directed a subsequent inquiry to the Department of Justice and Equality. When contacted about these privacy concerns, a Department of Justice and Equality representative referred the question back to Aramark, but said that the Reception and Integration Agency was now called the International Protection Accommodations Services unit. As of publication, Irish government sites continue to refer to the Reception and Integration Agency as the unit responsible for refugee services.

Ruth and others also complain of power abuses in the form of arbitrary rules. In July last year, a center manager in Newbridge, a town some 25 miles outside of Dublin, tried to ban the use of all electronic devices in private resident bedrooms between midnight and 7 a.m. Staff can dictate how much food a person may take from the canteen, how many rolls of toilet paper they can have each week, where and when they can have visitors, and when they can use the laundry machines.

Asylum seekers have little recourse in such situations. In theory, an avenue for formal complaints to a central ombudsman was instituted in April 2017 (prior to that, the only person an asylum seeker could complain to was the center manager, sometimes the one responsible for the mistreatment). But people are still afraid to complain, Charles told me. They worry they’ll be harassed in the center or moved to a different center entirely, like Mount Trenchard, which asylum seekers call “Guantanamo Bay”—an isolated converted old stately home some 25 miles west of Limerick City, run by private company Baycaster Ltd. The center’s occupants sleep as many as eight to a room, in beds separated by paneled dividers and curtains, and have complained of overcrowding, unhygienic living conditions, and being served food that was nearly inedible.

“RIA works to ensure that each person arriving in Ireland to claim protection has shelter, food and any urgent medical care required,” a Department of Justice and Equality representative wrote in response to overcrowding allegations. “The pressure our accommodation system currently faces is clear.”

“In direct provision, they say you are completely free—free to do what? Free to wait here in the same place?” Mfaco said.

The Irish state allowance, about $24 per week for adults until March 2019, when it was raised to $43, is higher than what some other countries provide, but it doesn’t stretch far, given that asylum seekers have to buy their own basic provisions. Mfaco puts aside part of his stipend to buy razors and other toiletries from the Tesco in Limerick. Ruth would love to have a pint with her friends, but settles for tampons and face cream. A basic phone plan to contact family and friends back home costs some $23 dollars per month—so expensive that residents sometimes share one phone plan with two or three friends. In April 2017, a mother in County Galway in the west of Ireland carried her eight-year-old son two miles back to her center, in the dark, after her child was discharged from the hospital late at night. The last bus had long left and she couldn’t afford the 10-euro taxi ride.

Technically, asylum seekers are free to refuse direct provision, but with no access to work for at least the first nine months, and many having arrived in Ireland with nothing, they have little choice.

In May 2017, nearly two decades after direct provision started, the Supreme Court of Ireland declared the total ban on work as unconstitutional. In June of the following year, asylum seekers were finally granted the right to work under new regulations. But the new regulation restricted work permits to those who have been in direct provision for at least nine months—the longest the country could legally deny work under European Union law—and those who have received a positive first decision on their asylum case. While Ireland did grant positive first decisions to around 1,000 applicants in 2018, many others remain either under a nine-month stay, waiting for a first decision, or are appealing. While they wait, they cannot work.

Even for those who do qualify for a work permit, opening a bank account for wage deposits usually requires identification—impossible for many to provide, given that the Department of Justice takes asylum-seekers’ passports upon arrival. With no bank account and with only a six-month working permit, many eligible asylum seekers still struggle to find employment, applying for self-employment permits to do handiwork or childminding—or in desperation, turning to other options.

Ruth has been propositioned twice. Once, as Ruth walked down the road from the single women’s center in Killarney, an Irish man pulled up alongside her in his car. He rolled the window down and whistled. He was an old man—“old enough to look like my grandfather; big belly,” Ruth recalled. “He put fifty euros on the dashboard and said, ‘Would you like to fuck?’”

Men, Ruth told me, know that young women in direct provision don’t have any money, and they take advantage of their impoverishment. She describes situations where men pick up young women in cars and ask them if they’d like to “go out”—a catch-all term often involving a date and some money in exchange for sex.

Reports of women in direct provision being forced into prostitution have been circulating for more than a decade. Ruhama, a Dublin-based organization that works with abused women forced into prostitution through poverty or trafficking, has stated in government policy proposals since at least 2010 that direct provision centers had “become targets for those seeking to exploit poor and vulnerable women through prostitution.” Six years later, RTÉ Radio aired an investigation into prostitution in centers throughout the country that interviewed twelve women who alleged that their poverty in direct provision forced them into sex work. At the time, Justice Minister Frances Fitzgerald asked for a report from the Reception and Integration Agency, and suggested Ireland might criminalize the buying of sex. Direct provision residents, however, suggest the conditions leading women to sex work have persisted.

Mfaco described a young single mother he knew in November of 2017 at Balseskin—the first reception center where all asylum seekers stay for the first few weeks—who sold sex for as little as €5 to men inside the center itself. He believes everyone, including the center staff, were aware of her situation and ignored it until the day she left her crying baby unattended while she was in the men’s block. They called authorities to take the child into state custody. RIA declined to comment on the allegations, citing “a legal duty to protect the identities of persons in the international protection process.” Mfaco recalls the child was eventually returned to the mother after a month’s separation.

These conditions are particularly tragic for asylum seekers who have already been victims of sex trafficking. In June 2019, a U.S. State Department report cited “inadequate privacy” and mixed-gender accommodation as factors in Ireland that may have exposed trafficking victims “to greater exploitation, and undermined victim recovery.”

In 2018, Donnchadh Ó Laoghaire, a Sinn Féin parliamentary representative for Cork-South Central and the party’s Justice and Equality spokesperson at the time, decried the system as “in effect a cash cow for those private companies who operate within it … It is a highly profitable model, profiting from the hardship and misery of others.” Eugene Murphy, a Fianna Fáil representative for Roscommon-Galway, last November called for an end to direct provision, describing it as “legalized people trafficking.”

While the Irish government does intend to implement changes, such as instituting self-catering facilities in the centers by mid-2020, change is slow if not altogether stalled. According to recent reports, the direct provision system is at 98.7 percent capacity with four centers housing more asylum seekers than their original contracted capacity. The Irish Times reported that Irish Department of Justice internal briefings indicate that centers have been asked to cram even more beds into housing space “without sacrificing standards.”

Asylum seekers must endure not just grim conditions within the centers, but hostility outside them. Two proposed centers were set on fire in suspected arson attacks—one in Donegal last November, while the other in County Roscommon was attacked twice, in January and February of this year. Their walls blackened and damaged in flames, neither can house asylum seekers at present, exacerbating the overcrowding problem.

For Ruth, the arson attacks are just one more grievance against a country where she already feels unwanted. Four years ago, she remembers landing in Dublin International airport and seeing fáilte, Irish for welcome, emblazoned in the hallways. It buoyed hope that she’d find refuge in this strange and faraway land. Years in direct provision have crushed her optimism. “There is no love here,” she said. “No care for an outsider. There is no welcome, no welcome to us whatsoever.”

She, Charles, Mfaco and the other thousands like them remain trapped inside a country they can’t fully enter and far from a home they can’t return to. They fear “losing it”—when residents, overcome by monotony or anxiety, wander the halls like zombies.

“Being young, everyone keeps on telling me that you still have a chance,” said Ruth, who was prescribed sleeping pills last year, for stress. “But they don’t understand what I’ve lost. I can’t get it back. I’ve lost a few of my youthful years and I can’t get it back.”

Mfaco had his asylum interview appointment on March 19, a full 17 months after he first entered direct provision. He hopes that his asylum claim will be accepted and he’ll be able to find a job and build a new life. But he knows that a final decision could still take months, even years—and he’s seen the toll that can take. Just days after his interview, he attended a memorial service for a man in direct provision who had hanged himself from a tree outside.