It’s been a grim few months for abortion rights in America. Multiple states, including Alabama and Georgia, have passed a wave of draconian new restrictions on the procedure, buoyed by the perception that the Supreme Court could soon overturn Roe v. Wade. Missouri is about to hit an even more dire milestone: Unless a judge intervenes on Friday, the state’s last abortion provider, a Planned Parenthood clinic in St. Louis, will be forced to stop performing the procedure.* This would mark the first time since 1974 that a U.S. state won’t have an abortion provider within its borders. Four other states—Mississippi, North Dakota, South Dakota, and Wyoming—have only one clinic as well.

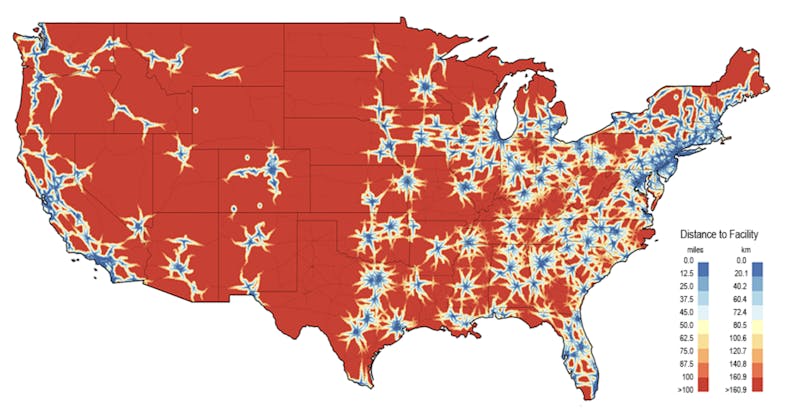

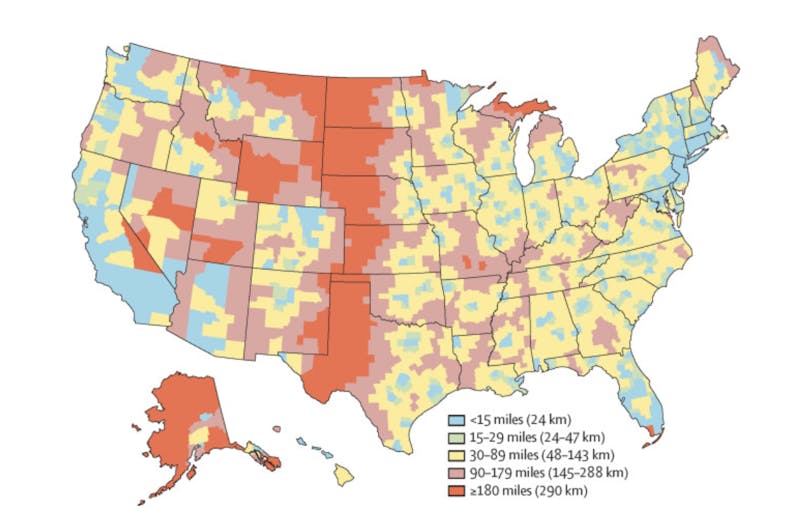

The Supreme Court’s landmark 1992 ruling in Planned Parenthood v. Casey bans abortion restrictions that impose an “undue burden” on access to the procedure. But that ruling is practically meaningless if women can’t reach a clinic in the first place. A 2017 study by the Guttmacher Institute found that between 2011 and 2014 alone, the number of abortion clinics in the Midwest declined by 22 percent, and in the South by 13 percent. And it’s not just rural women who suffer. Mother Jones reported earlier this month that 27 major U.S. cities are now more than 100 miles from the nearest abortion clinic. For lower-income women in those areas, a 200-mile round-trip drive to obtain the procedure may be a hurdle too high to surmount.

Some of these gaps mirror other deserts for healthcare access that arise in sparsely populated rural areas. But some of the gaps are more artificial thanks to targeted restrictions on abortion providers, also known as TRAP laws. Anti-abortion groups have discovered that even if the courts block and eventually overturn those laws, the measures can still have a significant impact on access.

The best example is from 2013, when Texas passed House Bill 2, which required clinics to meet the building standards of an ambulatory surgical center and required physicians who perform abortions to have admitting privileges at a hospital within 30 miles of the clinic. The law triggered three years of legal battles before the Supreme Court struck down both provisions in Whole Woman’s Health v. Hellerstedt in 2016. Justice Stephen Breyer wrote for a five-justice majority that the restrictions amounted to an undue burden on a women’s right to obtain an abortion because they severely restricted access to the procedure without providing any tangible health benefits. In a short concurring opinion, Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg quoted from Casey to underline the point that “laws like H.B. 2 that ‘do little or nothing for health, but rather strew impediments to abortion’ cannot survive judicial inspection.”

Even though the Texas clinics eventually prevailed, the law had already taken a heavy toll. The Texas Tribune reported that there were more than 40 clinics that provided abortions across the state when HB 2 passed in 2013. By the time the Supreme Court struck down the law three years later, that number had dropped to 19. The remaining clinics were concentrated in large, urban areas, which led to an immense geographic disparity in access. None remained open in the 500-mile stretch between San Antonio and El Paso.

A similar decline struck Missouri after state lawmakers passed a TRAP law in 2007 that imposed an admitting-privileges requirement. According to The Washington Post, the state went from five abortion providers in 2008 to just two in 2018. One of those two clinics stopped performing the procedure last year after its license expired during a legal battle with the state. The last remaining one, the Planned Parenthood clinic in St. Louis, sued Missouri officials earlier this week to prevent its own license from expiring in a similar standoff.

In theory, the Supreme Court’s ruling in Hellerstedt should have been a decisive blow to TRAP laws like those in Texas and Missouri. But Anthony Kennedy’s retirement from the court last summer changed that calculus. Friends and foes of abortion rights alike believe that Justice Brett Kavanaugh will be, at minimum, far more sympathetic to abortion restrictions than his predecessor. The post-Kennedy Supreme Court has not yet taken up an abortion-related case in full. But signs of the court’s new posture towards the practice are not comforting.

After the Hellerstedt ruling, the last two Missouri clinics at the time sued to overturn the state’s restrictions as well. But the Eighth Circuit rejected that effort last September by narrowing the breadth of the Supreme Court’s decision to keep the restrictions intact. “Hellerstedt did not find, as a matter of law, that abortion was inherently safe or that provisions similar to the laws it considered would never be constitutional,” Judge Bobby Shepherd wrote for the unanimous panel in Comprehensive Health v. Hawley. “Despite the district court’s assertions to the contrary, Hellerstedt’s analysis of the purported benefits of the law at issue were, of course, related to what the law in that case regulated: abortion in Texas.”

Conservative judges in other states took similar steps. Louisiana lawmakers passed a TRAP law in 2014 known as Act 620 that largely mirrored the Texas law struck down in Hellerstedt. A federal judge initially blocked the law from going into effect, but a three-judge panel in the Fifth Circuit overturned that decision and upheld the restrictions last September. As I noted last year, the Fifth Circuit’s ruling also used a tortured interpretation of Hellerstedt to conclude that the burden didn’t come from the law, but from the doctors’ inability to comply with it.

The Supreme Court narrowly voted to block the Louisiana ruling from going into effect in February, and the justices are now weighing whether they will hear the case next term. If the justices take up that case or any other one involving abortion restrictions, the court’s conservative members could take the opportunity to sharply reduce abortion access across the United States. Such a ruling would not be a sudden break with the past, though. It would mark the culmination of a long, relentless war of attrition against a woman’s right to control her reproductive future.

* An earlier version of this story incorrectly stated that the Planned Parenthood clinic in St. Louis would be forced to close. It would only be forced to stop providing abortions.